The Bluebird Beat: Tampa Red’s Marathon 1937 Lession

Recording for Lester Melrose at the Leland Hotel

During the years before World War II, Mayo Williams and Lester Melrose were the go-to men in Chicago for blues recording. Both worked as recording supervisors, music publishers, and A&R men. Both had been associated with Paramount Records during the 1920s. Earlier in that decade, Lester and Walter Melrose had opened the Melrose Brothers Music Company on Chicago’s South Side. Lester became a freelance A&R man in 1925. One of his early successes came in 1928 when he recorded Tampa Red and Georgia Tom Dorsey as “The Hokum Boys,” scoring a hit with “Beedle Um Bum” b/w “Selling That Stuff.”

By the mid-1930s, Melrose was supplying an array of talent for RCA Victor, Columbia, and their Bluebird and OKeh subsidiaries. “From March 1934 to February 1951,” Melrose claimed, “I recorded at least 90% of all rhythm-and-blues talent for RCA Victor and Columbia Records…. My record talent was obtained through just plain hard work. I used to visit clubs, taverns, and booze joints in and around Chicago. Also I used to travel all through the Southern states in search of talent, and sometimes I had very good luck.” Among those whose careers and legacies benefitted from Melrose’s golden touch were Big Bill Broonzy, Leroy Carr, Lonnie Johnson, Memphis Minnie, Tampa Red, Victoria Spivey, Roosevelt Sykes, Washboard Sam, Bukka White, Big Joe Williams, and Sonny Boy Williamson I.

Melrose is best known for his outsized role in producing and promoting the urbane, danceable, small combo sound that came to be known as the “Bluebird Beat.” In the landmark 1973 book Chicago Breakdown, Mike Rowe explained how it worked: “Melrose had more than a large stable of blues artists under his control. Since only a few of them had regular accompanists, most of them would play on each other’s records, and thus Melrose had a completely self-contained unit which made great sense economically, if less artistically.

“The instrumentation was generally constant: singer accompanied by guitar, piano, bass and drums, with occasional saxophones or harmonica. Whereas major companies had clumsily sought to record artists who sounded like each other, the Melrose machine provided them with artists who were each other! The final stage of this musical incest was completed when they started recording each other’s songs.”

Melrose, who couldn’t play an instrument, used his Wabash and Duchess Music companies to copyright songs composed by the artists he managed. Melrose explained his strategy to Alan Lomax: “I took my chances on some of the tunes I recorded being hits, and I wouldn’t record anybody unless he signed all his rights in those tunes over to me.” Bob Koester, for decades a fixture on the Chicago blues record scene, noted that Melrose, who was white, was “remembered with unusual fondness by the artists he recorded. There are noticeably fewer complaints of sharp practices and frequent praise of his musical perceptions and social attitudes.”

However, not all artists who recorded for Melrose shared this benevolent view. One example: In his 1977 interview with Living Blues, Eddie Boyd claimed, “I wasn’t making no money with Melrose, and I never was gonna make none…. Lester Melrose jived me into signing a contract—was a total enslaving contract for me. ’Cause I didn’t understand what I was doing, you know.” Shocked to learn that his postwar hit recording of “Blue Monday Blues” earned him only $167 in royalties—“one-fourth of one cent per record” sold—Boyd contacted Victor Records. “They told me they had nothing to do with that contract and my royalties, either,” he discovered. “They didn’t have no royalty contract with me. They paid royalties to Melrose. I was making all those records for Melrose, man. This cat’s sending hundreds of thousands of records on me, and I’m looking for a dishwashing job.” Big Bill Broonzy, among others, was likewise sharply critical of his financial dealings with Melrose.

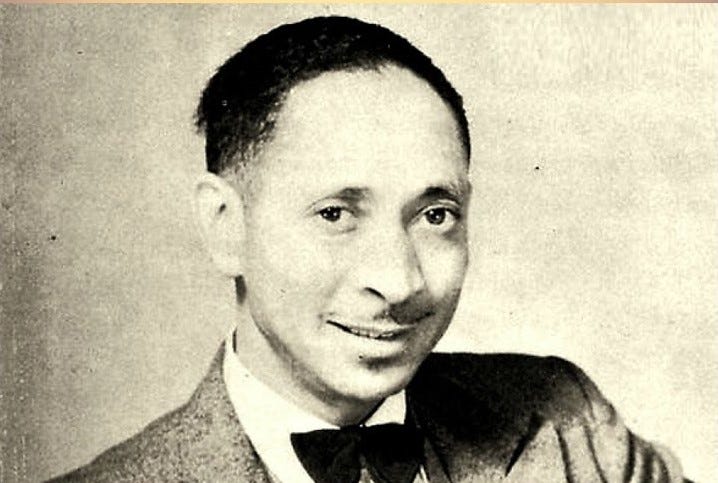

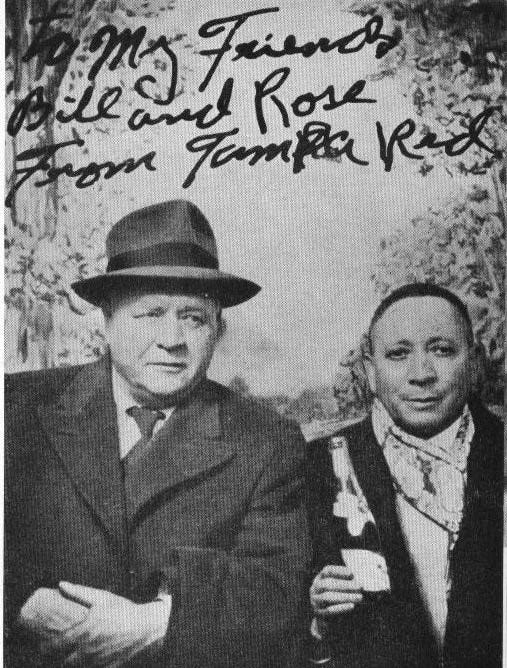

When musicians came into town to record, Melrose often relied on Tampa Red and his wife Frances to provide them with lodgings and a rehearsal space. Tampa Red, real name Hudson Whittaker, was a talented vocalist, superlative songwriter and slide guitarist, and a beloved figure among blues musicians. Their home at 3432 South State Street was a haven for blues musicians. As Blind John Davis remembered in Living Blues, Tampa’s house “went all the way from the front to the alley. He had a big rehearsal room, and he had two rooms for the different artists that come in from out of town to record. Melrose’d pay him for the lodging, and Mrs. Tampa would cook for them.”

Tampa’s drinking buddy Big Bill Broonzy was a frequent guest. At various times the Whittakers also hosted Memphis Slim, Willie Dixon, Jazz Gillum, Big Joe Williams, Sonny Boy Williamson I, Doc Clayton, Robert Lockwood, Arthur Crudup, Washboard Sam, Big Maceo Merriweather, Romeo Nelson, Little Walter, Elmore James, and Robert Lee McCullum, who’d record as Robert Nighthawk. Tampa tutored Nighthawk, whose potent postwar electric slide guitar style merged his mentor’s facile approach with a sustaining Delta whine. Whittaker rarely jammed with his house guests, though, preferring to relax with a drink and enjoy the goings-on. He worked hard at composing, though, scribbling lyrics and notes onto typewriter paper late into the night.

To save money, Lester Melrose would typically hold multiple sessions in a single day, using different configurations of well-rehearsed musicians. During the 1930s most of his sessions took place in Chicago studios. Between May 1937 and December 1938, though, he deviated from this pattern by arranging eight days of sessions at the Leland Hotel in Aurora, Illinois—a 50-mile commute, due west, from Tampa Red’s house.

In Today’s Chicago Blues, author Karen Hansen provided background on the Leland sessions: “No one is certain why RCA Victor or producer Lester Melrose selected the Leland; some speculate that a location outside of Chicago was chosen to avoid union conflicts. Others say that the Sky Club had good acoustics. Whatever the reason, the Leland was an attractive choice: at the time, it was the tallest building outside of Chicago. On the top floor the Sky Club was a spacious ballroom where jazz-inspired big bands often played to all-white audiences. The makeshift recording studio consisted of a couple of chairs and a couple of microphones, according to Henry Townsend. The records were cut on wax, he said, because magnetic tape and reel-to-reel recorders were not yet in widespread use. Lester Melrose would bring several musicians into the studio at once, thereby producing a number of sides in a minimum amount of time. Each musician would take a turn as lead performer and then back the others on their recordings.”

For the first Lelend session, held on May 4, 1937, Melrose caravaned an array of talent to the hotel. As the day progressed, Tampa Red played piano on two solo tracks and cut a half-dozen sides credited to Tampa Red and The Chicago Five, with Bob Black on piano and Willie B. James (a.k.a. “Willie Bee”) on guitar. Merline Johnson, Mary Mack, John D. Twitty, Charley West, and Washboard Sam with Big Bill Broonzy fronted songs as well. The following day, Sonny Boy Williamson I kicked off his recording career with “Good Morning Little School Girl” and “Blue Bird Blues.” Making his debut at this session as well, Robert Lee McCoy recorded his “Prowling Night-Hawk.”

Not long after the May sessions, Tampa Red met pianist Blind John Davis, who would become a close friend for the remainder of his life. In our June 1979 interview for Keyboard magazine, I asked Davis how their association had come about. “What happened was I wanted to make records,” Davis responded, “so I calls and I finds out Melrose’s phone number. Then I contacted him, and he tells me to meet him on the South Side of Chicago. So I meets him out there, and he takes me to this fellow Washboard Sam. And Washboard Sam was a very difficult person to work with, because he would do a song like this today, and you go back tomorrow and he done changed it. Then he’d fault the musician. So he was a terrible guy to work with. Him and I couldn’t hit it off.

“At that time this Wallis Simpson and this Prince of Wales had just gotten married. And Tampa Red had made a number, “She’s More to Me Than a Palace is to a King.” So they take me over to Tampa’s house, and Tampa had made this number in a minor key. So Tampa’s wife was sick at the time, in the bed. So when I got there, Melrose introduced me and said, ‘Tampa, this man might can play your number.’ Tampa said, ‘No, I done had three or four guys up here, and they couldn’t play it.’ So I says to Tampa, ‘Well, mister, play it. Let me hear a little bit of it, and I’ll see if I can play it.’ He played a little of it, so when I sit down, I played it. His wife hollered out of the bedroom, ‘Tampa, that’s the one!’ So he’s the one that give me my break. Ever since then, I been with Tampa.” This fortuitous association led to Davis becoming an accompanist for other Bluebird artists.

Melrose booked the studio in the Leland Hotel for Monday, October 11, 1937. The marathon day-long session that would produce 78s credited to Tampa Red, Curtis Jones, Red Nelson, Lee Green, and Victoria Spivey’s sister, Addie “Sweet Pease” Spivey. Pianists Blind John Davis and Aletha Dickerson, guitarists Big Bill Broonzy and Willie B. James, and an unidentified drummer and horn section were also present to provide backup as needed. In all, twenty-eight songs were successfully recorded.

Tampa Red went first, cutting ten songs onto matrixes 014324-1 through 014333-1. He began with four sides featuring a small band with Blind John Davis and a trumpet player, tenor saxophonist, and drummer. Their first number, “You’re More Than a Palace to Me,” was the song Blind John Davis had auditioned with. Tampa delivered his lyrics from the perspective of King Edward VIII, then in the headlines for abdicating his throne to marry an American divorcee. Set to an easy-swinging tempo, its winsome arrangement was perfectly suited for cheek-to-cheek dancing. Tampa, who sang with easy-to-understand diction, let the trumpeter take the solo, encouraging him with the spirited phrases “Yeah,” “I hear ya,” “Uh-huh,” and “That’s it!”:

I’ve given up a palace, a crown and everything

But long as you’re mine, I’ll gladly bear the blame

For you’re more to me than a palace is to a king…

But life for me without you wouldn’t mean a thing

I’d be like a snowball melting in a flame

For you’re more to me than a palace is to a king

The ensemble picked up the pace for the rollicking “Harlem Swing,” with Davis stepping out on the 88s before the sax kicked in. This was pure party music:

Everybody from miles around

Are here in town to break ’em down

They all wild about the mellow sound

So let’s get pumpin’ loud

Yeah, man, you understand

Everybody grab somebody

And do that Harlem swing

“Oh Babe, Oh Baby” combined a swinging ensemble arrangement with bluesier lyrics than the first two songs. Davis played a brilliant chorus, and then the saxophonist and trumpeter took their turns:

I know, baby, what you’re trying to do

You can’t love me and my buddy too

Oh babe, ah babe, oh baby

If I had a-known like I know now

I wouldn’t have been tied up with ya no how

Oh babe, ah babe, oh babe

Tampa’s final ensemble master, “I’m Gonna Get High,” kept the party going:

I’m gonna get high

And it ain’t no lie

And swing alone and have a ball

I’m gonna get high…

Upon their release by Bluebird, all four of these sides were credited to “Tampa Red and The Chicago Five.” The original labels described the selections as “Fox Trot, Blues Singer with Orchestra.”

Ry Cooder observed that with swinging tracks such as these, “Tampa Red ironed out all the kinks. He made it more accessible and played it with more of a modern big band feeling—like a soloist, almost. He changed it from rural music to commercial music, and he was very popular as a result. He made hundreds of records, and they’re all good. Some of them are incredibly good. You gotta say, okay, that’s where it all starts to become almost pop. And he had a great guitar technique, for sure. He put it all together, as far as I’m concerned. He got the songs, he had the vocal styling, he had the beat. It’s a straight line from Tampa Red to Louis Jordan to Chuck Berry, without a shadow of a doubt.”

For the next four songs, Tampa Red played piano while Willie B. James supplied the guitar parts. A pure Southern-style blues with effective falsettos, “Delta Woman Blues” was likely designed to resonate with record buyers attracted to the then-popular Leroy Carr-Scrapper Blackwell duets and Tampa’s earlier, pre-ensemble records. Willie Bee, as he was credited on the label, played forward-leaning single-string accompaniment throughout, but was smothered in the mix beneath Tampa’s booming piano.

He positioned his guitar closer to the microphone for “Deceitful Friend Blues,” which was structurally and melodically similar to “Delta Woman Blues.” Tampa’s piano playing is more adventurous on this song, likely the result of his having warmed up. James’s flat-picked string bends and note choices suggest he’d drawn inspiration from Lonnie Johnson.

Tampa, by all accounts a dedicated husband, used his next song, “Wrong Idea,” to dispense advice to men inclined to cheat on their significant other:

You men got a habit

That you know is wrong

Stay out cheating on your woman

Maybe all night long…

You want your woman jealous

All alone by herself

But how you expect to get it, buddy.

When you got somebody else

Men you got the wrong idea

Just as sure as you’re born

Don’t blame your woman

If things at home go wrong

Tampa wrapped up his piano tracks with the adult-themed “Whoopee Mama,” singing about the grim fate awaiting a woman who parties too hard:

I got a whoopee mama

She makes whoopee all the time (x2)

She stays full of dope and liquor

And clowns all over town…

My whoopee mama

Treats me like a slave (x2)

I’m goin’ to buy me an Army special

And put my baby in her grave…

Whoopee mama

I’m going to mow you down

I’m gon’ send your beautiful body

To some lonesome buryin’ ground

Fans of Tampa’s slide guitar style will enjoy the last two songs he recorded that day, “Travel On” and “Seminole Blues.” He played both selections with a metal-bodied resophonic guitar set to a Vestapol tuning.

Growing up in Florida, Tampa had seen Hawaiian guitarists play these instruments lap-style, but he taught himself to play by holding it the standard way and using a thumbpick to strike the strings. “Instead of all that finger doublin’ and crossin’, I got me a bottleneck,” he explained to Jim O’Neil. “I used two, three, maybe four strings sometime. It’s got a Hawaiian effect. I couldn’t play as many strings as a fella playin’ a regular [lap-style] Hawaiian guitar, but I got the same effect. I was the champ of that style with the bottleneck on my finger.” Willie B. James accompanied him on both songs, flatpicking bass notes beneath Tampa’s slide figures.

Played in the key of E, “Travel On” is notable for its mournful single-string slides and upbeat lyrical message:

When you are doing

The best you can

And the one you loving

Don’t understand

Don’t get discouraged but keep a-tryin’ and travel on…

Applying a capo to his first fret or tuning his guitar up a half-step, Tampa played “Seminole Blues” in the key of F. His bottleneck solos are more ambitious on this song, with occasional multi-string glisses reminiscent of Hawaiian music. The word “Seminole” in this leaving blues refers to a passenger train, the Seminole Limited, that ran between Chicago and Jacksonville, Florida. The guitar interplay is brilliant throughout this often-anthologized track:

My baby’s gone, won’t be back no more

She won’t be back no more, whoa

My baby’s gone, won’t be back no more

She left me this morning, she caught that Seminole…

She gimme her love, even let me draw her pay

She let me draw her pay, yeah

She give me her love, even let me draw her pay

She was a real good woman but unkindness drove her ’way

When Tampa was finished recording, Willie B. James accompanied Curtis Jones and Lee Green. Blind John Davis and a second guitarist believed to be Big Bill Broonzy backed Red Nelson, and Aletha Dickerson played piano for Sweet Pease Spivey.

In his excellent liner notes for Tampa Red: The Bluebird Recordings 1936-1938, which anthologizes all of the tracks discussed here, Jim O’Neil wrote, “If ever a blues artist proved himself a man of the times, Tampa Red did from 1936 to 1938, when he was recording for Bluebird. Already established as one of the country’s premier blues stars, Tampa Red, previously billed as ‘The Guitar Wizard,’ suddenly headed in not one, but two, distinct directions with his music, both of which relegated his famed guitar work far to the background or out of the picture altogether. For three years, Bluebird simultaneously recorded and marketed Tampa Red as a dance-band pop singer (with a studio group called the Chicago Five) and as a blues singer-pianist solidly in the mold of the recently departed Leroy Carr…. His Chicago Five songs proved he had his pulse on the mainstream of popular American culture. Together, the Chicago Five sessions and the companion blues sides offer one of the broadest portraits of American culture ever conceived by a blues artist.”

After his 1937 session at the Leland Hotel, Tampa Red became one of the first Chicago blues musicians to acquire an electric guitar. He recorded with it for first time on December 16, 1938, for the session that began with “Forgive Me Please.”

During the ensuing years Tampa Red stayed close to home. For about nine years he gigged just yards from his house at the H&T club, performing solo or in the company of Willie B. James or pianists Big Maceo, Sunnyland Slim, or Johnnie Jones. In 1945 he moved from Bluebird to its parent label, Victor. Although slowing down, he stayed current, delving into horn-driven big-band jump a la Louis Jordan, powerhouse boogie-woogie, and as-yet-unnamed rock and roll. “When Things Go Wrong For You (It Hurts Me Too),” from 1949, made it into the national R&B charts. His last R&B hit was “Pretty Baby Blues,” recorded for RCA in 1951.

As he approached the age of fifty, Whittaker retired from the night life to care for Frances, who had a serious heart condition. Tampa’s wife was “mother and God to him both,” as Sunnyland Slim put it, and her death in 1954 left Tampa a broken man. He quit performing and escalated his drinking. Rumors of his erratic behavior began to circulate, and for a while he was confined to a mental hospital. “I got sick and had a nervous breakdown,” he explained, citing his inability to refuse a drink as the cause.

He was coaxed out of retirement in 1960 to record two albums for Prestige/Bluesville. By then his once-brilliant slide playing was replaced with kazoo solos as he picked electric guitar counterpoint to his weary-voiced lyrics. After a few live performances, he reportedly stowed his guitar beneath his bed. During the early 1970s, when labels began reissuing his songs on LPs, he was living on welfare with his companion, Effie Tolbert, on Chicago’s South Side. He enjoyed sharing beers and hand-rolled Bugler cigarettes with old friends and the occasional journalist, but his recollections of his music career were few and far between.

Tampa Red spent his final years in Chicago’s Central Nursing Home, where Blind John Davis looked after him. On March 19, 1981, Hudson Whittaker passed away. He’s buried in Mt. Glenwood Memory Gardens in Glenwood, Illinois. In his autobiography, Big Bill Broonzy had accurately predicted, “There’s only one Tampa Red, and when he’s dead, that’s all, brother.”

###

The Blind John Davis and Ry Cooder quotes are from their interviews with the author. For a wealth of additional biographical information about Tampa Red, check out Jim O’Neil’s liner notes for the Tampa Red: The Guitar Wizard, which are downloadable here: The Guitar Wizard liner notes.

###

Portions of this article appeared in my “Let It Roll!” feature in Living Blues #290.

For more coverage of pre-war blues, check out these Talking Guitar articles: The Birth of the Blues, The First Blues Recordings, The Atlanta Blues, The Origins of Spanish and Vestapol Tunings, The Great 1930 Mississippi Delta Blues Session, Barbecue Bob, Blind Blake, Blind Boy Fuller and Rev. Gary Davis, Son House and Willie Brown, Mississippi John Hurt, Papa Charlie Jackson, Lonnie Johnson, Robert Johnson, Blind Willie Johnson, Blind Willie McTell, Memphis Minnie, Ma Rainey, Johnny Shines, Victoria Spivey and Lonnie Johnson, The Georgia Cotton Pickers, Curley Weaver, Booker “Bukka” White, Rev. Robert Wilkins, Talking Blues With Keith Richards, and “You Gotta Move”: The Country Blues Roots of the Rolling Stones.

###

Help Needed! To help me continue producing guitar-intensive interviews, articles, and podcasts, please become a paid subscriber ($5 a month, $40 a year) or hit that donate button. Paid subscribers have complete access to all of the 200+ articles and podcasts posted in Talking Guitar. Thank you for your much-appreciated support!

© 2025 Jas Obrecht. All right reserved.

Seminole Blues

You can sing Chuck Berry lyrics to that Tampa Red melody