In celebration of International Women’s Day, here’s an article on the great Ma Rainey and her best day in the studio, which found her working alongside young Louis Armstrong.

While Bessie Smith is often cited as the early blues’ foremost female singer, eyewitness accounts contend that Ma Rainey held the distinction of being its greatest performer. This intense, warm woman was a living link between minstrelsy, the earliest blues, and vaudeville. Her deep contralto sounded rough and unsophisticated compared to other commercial blues women, but she projected a great depth of feeling and was adored by audiences. Her Paramount 78s sold well, especially in the rural South, where she had long captivated the hearts of the rugged workers in fields, levee camps, and lumber yards. Her audiences especially appreciated her earthy lyrics. As poet Sterling Brown explained to Paul Oliver, “Ma really knew these people. She was a person of the folk. She was very simple and direct.”

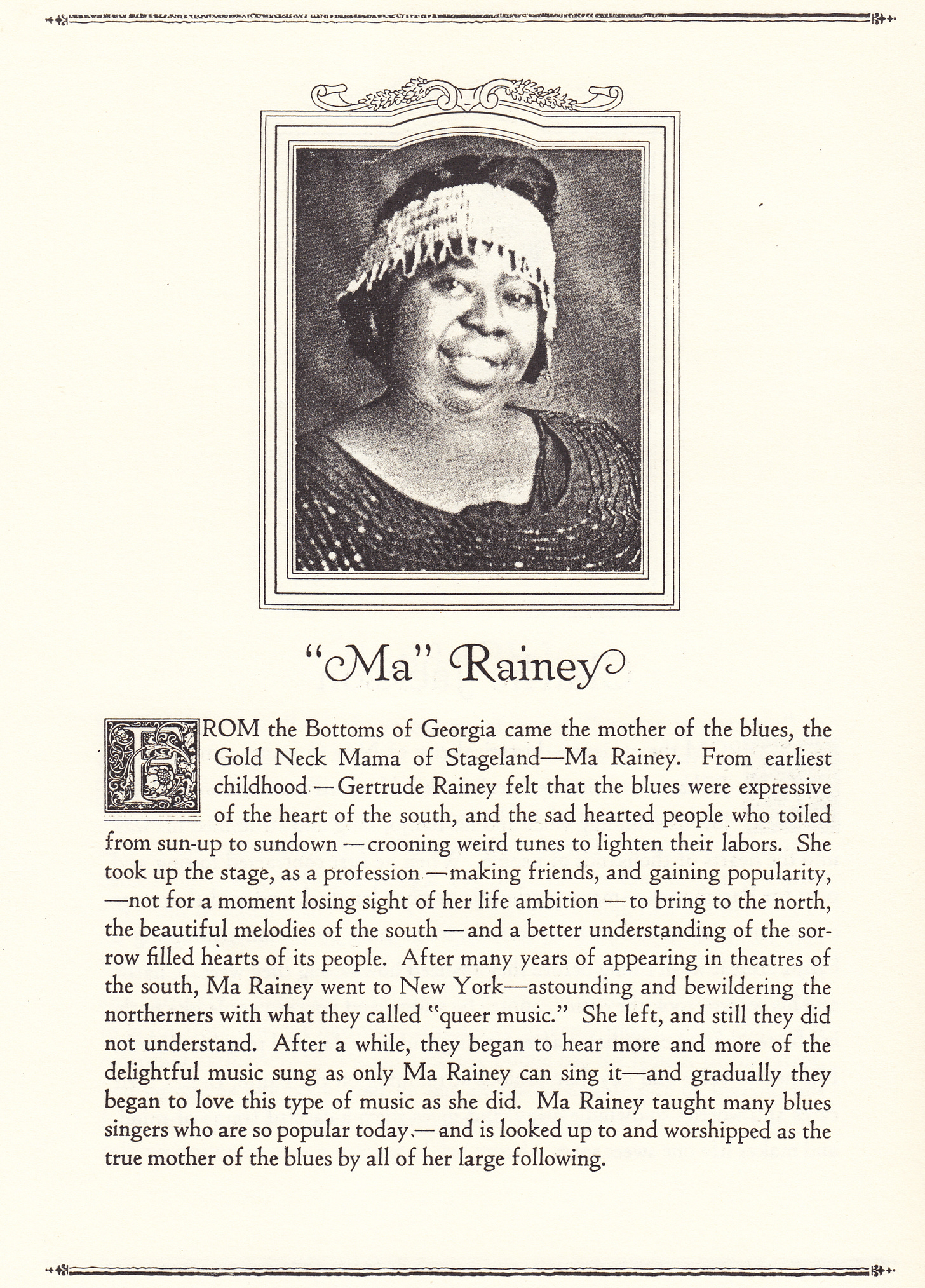

Ma Rainey was prominently featured in the 1926 promotional publication issued by her record label, The Paramount Book of Blues. Her bio page declared, “From the Bottoms of Georgia came the mother of the blues, the Gold Neck Mama of Stageland – Ma Rainey.” There was more truth than hype in the bio’s conclusion: “Ma Rainey taught many blues singers who are so popular today – and is looked up to and worshipped as the true mother of the blues by all of her large following.”

She was born Gertrude Pridgett. While most biographies list April 26, 1886, as the date of her birth, the 1900 Census for Columbus, Georgia’s Ward 5 gives September 1882 as the birth date for “Gertrude Prigett.” In their essential reference book Blues: A Regional Experience, Bob Eagle and Eric S. LeBlanc also offer the 1882 date and list her place of birth as Russell County, Alabama – possibly in Marvyns or Uchee. According to Ma’s brother, Thomas Pridgett, Jr., “at a very early age her talent as a singer was very noticeable.” When Gertrude was about ten, her father passed away and her mother took a job with the Central Railway of Georgia.

After the turn of the century the teenager made her singing debut with the Bunch of Blackberries troupe at the sumptuous Springer Opera House in Columbus, Georgia. Soon afterward, she joined a traveling tent show. In an interview with musicologist John Work and poet Sterling Brown at Nashville’s Douglass Hotel during the 1930s, Ma claimed that she heard blues for the first time around 1902, when her tent show played a small Missouri town. “She tells of a girl from the town,” Work wrote in American Negro Songs, 1940, “who came to the tent one morning and began to sing about the ‘man’ who had left her. The song was so strange and poignant that it attracted much attention. Ma Rainey became so interested in it that she learned the song from the visitor and used it soon afterward in her act as an encore. The song elicited such response from the audience that it won a special place in her act.” Although they were not yet called blues, Ma reported that she had often heard similar songs as she traveled the South.

William M. “Pa” Rainey, a singer, dancer, and comedian, was smitten by her charms. She accepted his proposal, and in February 1904 became “Ma” to his Pa. The couple, who stayed together about a dozen years, performed song-and-dance routines for a variety of Black minstrel troupes. As her fame spread, “Madame Gertrude Rainey” became a headliner with the Smarter Set, the Florida Cotton Blossoms, Shufflin’ Sam From Alabam’, and Rainey’s Rabbit Foot Minstrels. Accompanied by a jug band, jazz combo, or pianist, Ma sang pop, blues, and novelty numbers during this era and was renowned for her dancing and comedy. “She was always a great star, from way back there about 1912,” remembered Rev. Thomas A. Dorsey in Living Blues. Dorsey, who would lead Ma’s touring band during the mid-1920s, first saw Ma and Pa Rainey when he was a popcorn server at Atlanta’s 81 Theater. Around this time, a young chorus girl named Bessie Smith joined the troupe. It’s unknown whether Ma gave Bessie singing lessons, but Bessie clearly emulated the older singer. From 1914 to 1916 Ma and Pa traveled with Tolliver’s Circus and Musical Extravaganza, billed as “Rainey and Rainey, Assassinators of the Blues.” When their days of assassinating together ended, Ma Rainey carried on as a single woman.

By 1917 Ma Rainey, solo artist, was packing them in. The fact that some of her shows were integrated – half of the tent reserved for whites, half for Blacks – testifies to her drawing power in the South. When whites outnumbered Blacks – not an uncommon occurrence, according to witnesses – the overflow sat peacefully in the Black section. The two-hour show typically opened with three jazzy numbers by the band. Then, with a musical crescendo and flash of lights, the curtains opened on a line of chorus girls showing knees and laced-up high heels. Ma employed chorus boys too, who were almost invariably “light brownskins” or “yellows.” Next up was a hilarious skit, such as the one described in Sandra Lieb’s 1981 biography, Mother of the Blues: A Study of Ma Rainey, involving trained chickens, a coop, a thief, and a shotgun-toting “brownskin” made up to look like a bearded cracker.

After additional songs and routines, Ma Rainey would make her grand entrance. Her voice big and powerful, she’d sing songs such as “Walkin’ the Dog,” “I Ain’t Got Nobody,” “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” “Tishomingo Blues,” “Jelly Roll Blues,” “Memphis Blues,” and her favorite encore, “See See Rider.” She’d dance and crack jokes about craving pigmeat (i.e., young men). At the conclusion of Ma’s set, the whole troupe would join in for the grand finale. Afterwards, they’d pack everything into a train car and move on. In Jim Crow country, the troupe carried their own food, since people of color weren’t allowed in dining cars. They had to sleep on the train or with Black families along the way.

On occasion Ma traveled with a choreographer. While she might scold her girls for not lifting their legs high enough during rehearsal, she seldom lost her temper and was never violent. Offstage, she acted more like a religious person than a celebrity, never cursing and giving generously to churches and charities. Her employees were not permitted to drink alcohol during the evening of the show.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Talking Guitar ★ Jas Obrecht's Music Magazine to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.