Blues Guitar: The Origins of Spanish and Vestapol Tunings

How Old-Time Parlor Guitar Influenced Early Blues Musicians

How did fanciful European parlor music influence the creation of the blues? In a more profound way than most fans realize. What follows is one of the most fascinating and least understood chapters in blues history.

In times before radio, records, and electric lights, people often played music to amuse themselves after dinner and at social gatherings. “Parlor guitar,” a favorite European musical fare during the late 1700s, caught on in America. Played with bare fingers on small-bodied instruments, parlor guitar became immensely popular, as evidenced by the stacks of musical scores published during the 1800s. Many of these compositions called for the guitar strings to be tuned to an open chord. The most common tunings, open C (with the strings tuned C, G, C, G, C, and E, low to high) and open D (D, A, D, F#, A, D), clearly had European origins. The origins of open G, a favorite banjo tuning, are more difficult to trace. Two parlor compositions in particular would play a crucial role in the development of the blues.

Our journey begins with Henry Worrall. Born in Liverpool, England, in 1825, Worrall moved to the United States in 1835 and eventually settled in Cincinnati, Ohio. For a while he worked as a glasscutter’s apprentice, but his passion was guitar music. A skilled performer and composer, he became a music professor at the Ohio Female College. One of his prize guitar students, Mary Elizabeth Harvey, became his playing partner and wife. In 1856, he completed Worrall’s Guitar School, or The Eclectic Guitar Instructor, which remained in print through the 1880s.

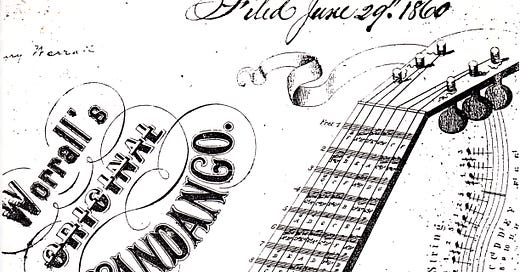

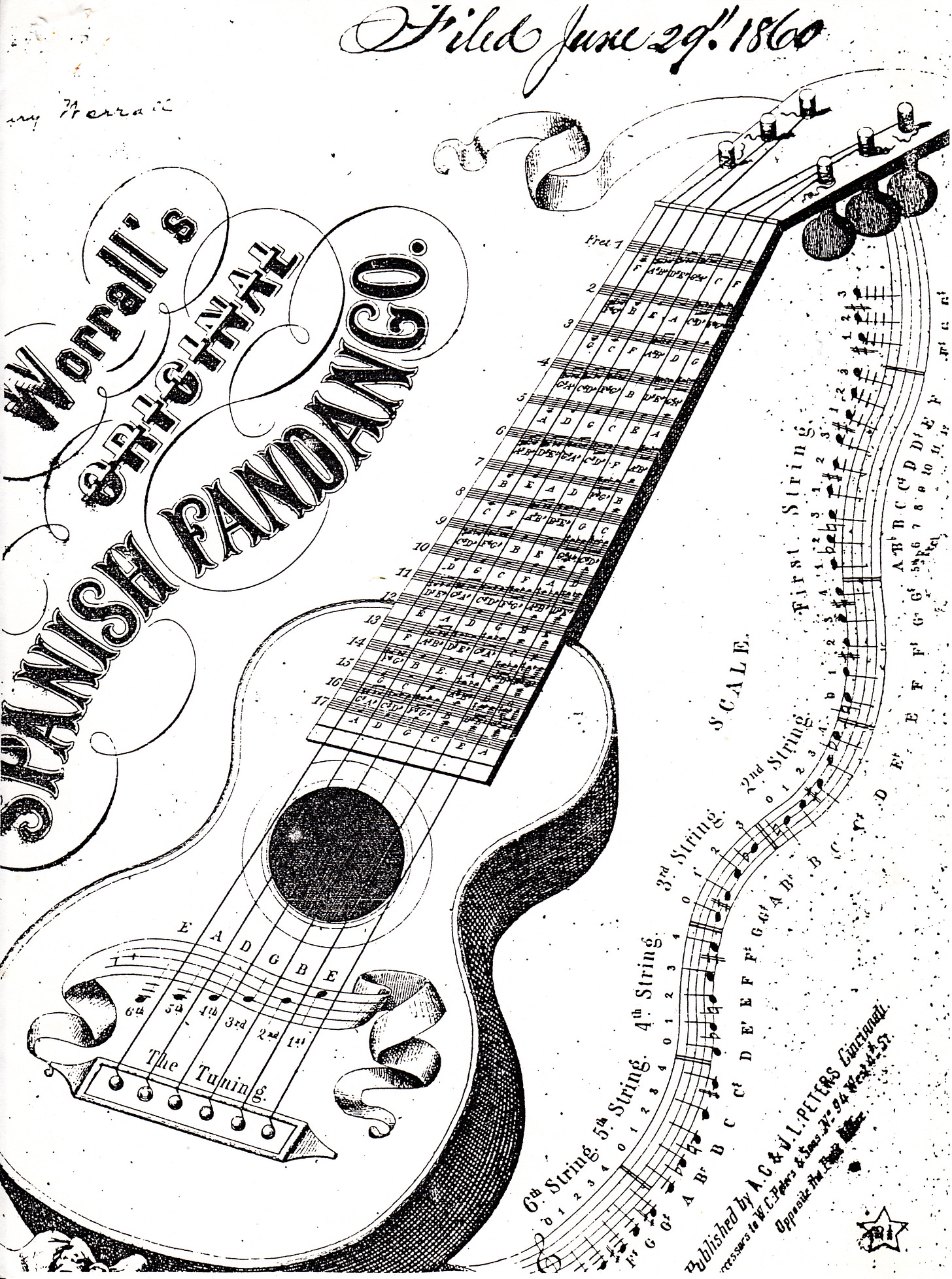

On June 29, 1860, Worrall walked into the Clerk’s Office of the Southern District Court of Ohio and filed copyrights for two instrumental guitar songs. “Worrall’s Original Spanish Fandango” called for the guitar strings to be tuned to an open-G chord (D, G, D, G, B, D, from low to high), with the explanation that the music was to be read as if the guitar were in standard tuning. Some of the song’s flourishes sounded like watered-down versions of earlier nineteenth-century European music. Its vivace finale, for instance, could have worked as a Rossini opera coda. But with its lilting melody and easy chord changes, this song is clearly the direct ancestor of one of the most common blues strains.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Talking Guitar ★ Jas Obrecht's Music Magazine to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.