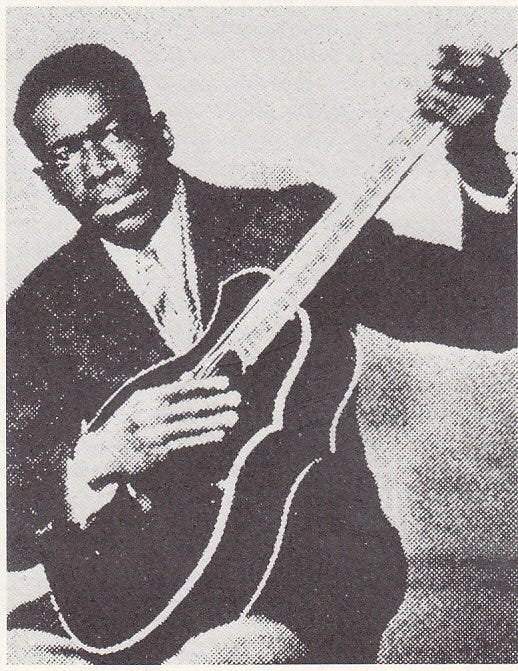

During the first decades of blues recording, Curley Weaver was one of Atlanta’s most beloved bluesmen and Blind Willie McTell’s closest friend. During a seven-year period beginning in October 1928, he recorded an impressive array of 78s under his own name, as a member of the Georgia Browns and Georgia Cotton Pickers, and as a sideman for Blind Willie McTell, Buddy Moss, Ruth Willis, and others. In 1949 he briefly resurrected his recording career, recording solo and alongside McTell.

Born on March 25, 1906, Curley James Weaver was raised around Walnut Grove, Georgia. He was childhood friends with Robert and Charlie Hicks, who would make 78s as Barbecue Bob and Laughing Charlie Lincoln. Weaver’s mother, Savannah “Dip” Weaver, played guitar and taught the three youngsters frailing techniques and open-G tuning. After the Hicks brothers moved to Atlanta, Weaver played house parties and dances with Eddie Mapp, a gifted young harmonica player who excelled at everything from slow, mournful blues to rollicking train imitations.

In 1925 Weaver and Mapp moved to Atlanta, where the Hicks brothers, who’d yet to record, helped them launch their careers. With his easygoing personality and knack for accompanying others, Weaver became a favorite among local musicians. Their associate Buddy Moss told Blues Unlimited magazine, “I think people liked Curley best. Curley was a guy. He could really raise behind you and he could take up the slack. You didn’t have to wait for him.”

Barbecue Bob arranged for Weaver to record his first 78s for Columbia Records in October 1928. Played without a slide, his first recording, “Sweet Petunia,” was a cover of a song Lucille Bogan had recorded in 1927. Vocally, his performance resembled country musician Jimmie Rodgers, who was enormously popular at the time.

The record’s flip side, “No No Blues,” was pure Curley Weaver, with snapping bass strings, driving strums, and the light, wavering slide sound that would become the most distinctive aspect of his early guitar style. As his slider reached its notes, Weaver would often give it a short, rapid shake to create a propulsive, wobbling sound. He achieved superb sonic balance between bass and treble, probably using his bare thumb on the bass strings while plucking slid notes with his index, middle, and ring fingers. Few other guitarists played slide this way, and by the mid 1930s this sound had pretty much vanished from the blues. But Weaver was far more than a one-lick wonder with a slide.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Talking Guitar ★ Jas Obrecht's Music Magazine to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.