Ry Cooder and Ali Farka Touré first crossed trails in London in 1992. As a token of his admiration, the legendary African musician presented Cooder the one-string lute he’d played as a child. The musicians agreed to collaborate in the future.

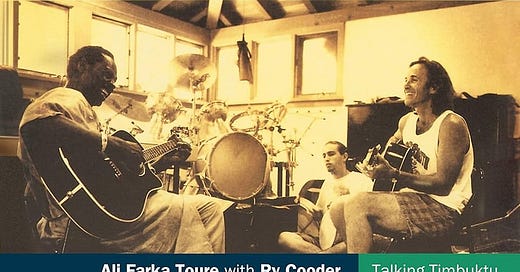

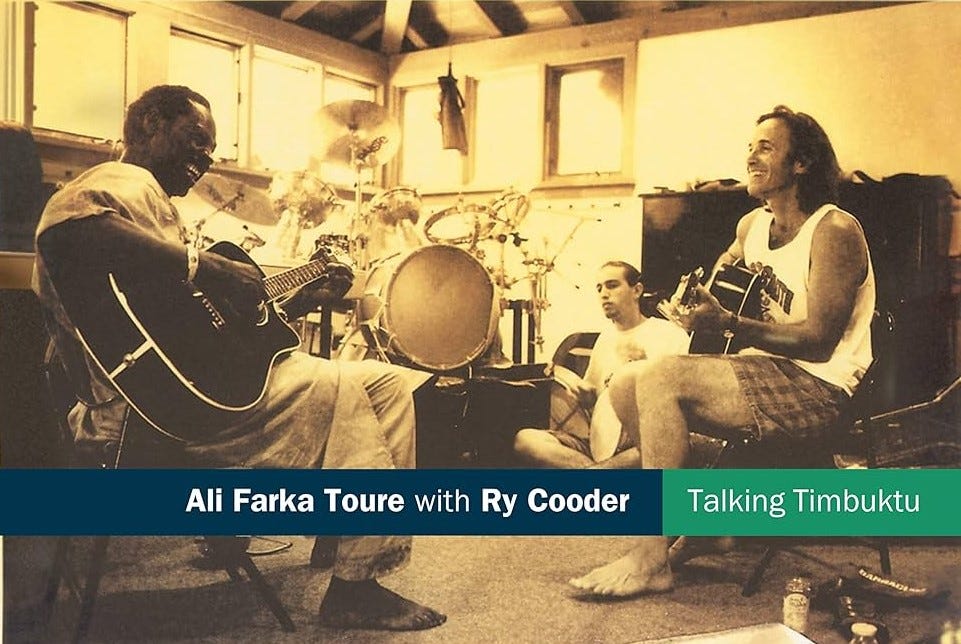

Two years later, Touré journeyed from Timbuktu to the U.S. for a tour and to record an album, Talking Timbuktu, for the Rykodisc label. Asked to produce the album and sit in on guitar, Cooder quickly agreed. “I’m glad to do it,” Cooder told me at the time. “Ali Farka is a charismatic man who’s got a lot of power and strength. He’s ferociously energetic, so his vibe and everything goes out. He’s like the village headman. He’ll just come in and reset the molecules in the room.”

During the sessions, Touré sang and played electric guitar, six-string banjo, and an African gourd fiddle called a njarka. “His guitar approach is very simple,” Cooder observed. “He’s got a couple of semi-open tunings, more like what they used to call ‘Vastapol’ [open D] than anything else. He plays with his thumb and first finger, and he’s got that African rhythm that you can’t beat—perfect inside groove, no matter what, and real steady, sure, and confident. It’s an expression of his tremendous self-confidence, which is like miles wide. The guy is a big, strong, important man.”

Joining them in the studio were Texas bluesman Gatemouth Brown, drummer Jim Keltner, bassist John Patitucci, and Hamma Sankare and Oumar Touré from Touré’s band. As Talking Timbuktu was being mixed, a Rykodisc publicist recruited me to do an interview with Ry to be used for promotional purposes. Here is that complete May 12, 1994, conversation.

***

What’s the challenge of playing with Ali Farka Touré as opposed to someone like John Lee Hooker or Pops Staples?

[Laughs.] Oh, well, there’s nothing to it. These guys are all the same. I’ll tell you what it comes down to: Here you have an African Black man, okay? So they don’t do what we do or what we’re used to doing or what we borrowed or learned from Black people over here, right? Of course, it’s not fair to include Pops—he’s country. See, country people aren’t so aggressive. They’re not so full of craziness and ambivalence, and so they tend to play in a more relaxed way. I mean, even poor, beaten-down, fucked-over American Black people, when they’re from the country, they have kind of a centered calm about what they do.

Sometimes it’s almost a gentleness.

That’s what I’m getting at. Now, you take your African Black folks. They’re not beaten down at all. I mean, look at what we’ve just witnessed in the news. As a big group, I guess I find them to be—I don’t know about these poor people in Rwanda, okay?—but as musicians and as musical people, they seem to be very upbeat and positive and optimistic. And that gives them a different kind of a flow when they play.

You can sit there with Ali Farka Touré, and right away you realize he’s not foot-stomping it down to the bricks. He’s not chewing the legs off the furniture. He’s not like beating it out. So you have to get to kind of a soft place with a guy like that, with him. He’s very tough and he’s very strong and all that, but when they play music, they don’t play it in an aggressive way or in kind of a thrusting way. It’s more like tune in and turn on to it, you know.

I get the feeling that all through the years—thousands, eons worth of years—what they must have known or had going was a sense that the music is all there, and all you have to do is just become a conduit for it. So it’s not about anything personal, like you’re about to take charge.

Do you hear ancient tradition when Ali plays?

Yeah, sure. He doesn’t take charge or run the show. It’s not with an intent to lead or force the issue. It’s like turn your radio on, you know? Turn on the little machine and go, which means you don’t do the thing where you take charge. I don’t think Africans do that. I think they just go with the flow that’s already there. And they have a strong sense of that. That may seem abstract to us, but I think it’s very real to him because he’s just participating for a moment, and then later on he’ll smoke a cigarette and have a cup of coffee.

But when he’s playing, it’s a trance thing. I think that’s the true sense of what that is—not a Grateful Dead type trance, but trance in the sense of just grab a hold. So it means you don’t have to be the aggressor or the leader or the boss or the owner of the thing. So that’s the difference.

He treated you as an equal?

Well, sure. You see, his trip with you is like you come in, you’re a master. And he doesn’t say too much, except he calls me “master” all the time. First I thought, “Oh, what’s that?” Then it’s obvious enough that it means we’re all together, we’re on par with one another—or we wouldn’t be together. And when masters get together, they do good things, so it’s a way of encouraging your efforts and it’s a way of encouraging your high expectations.

In other words, we all know what we know. There’s a respect in that. And I think Africans have that too, where they want to acknowledge each other in an important way. So there’s no suspicion, there’s no competition, and there’s none of that “I’m gonna cut you down.” No way! “You’re great, but I’m gonna cut you”—none of that. It’s gone. It does not operate. It does not exist. Somebody may be like that over there, but I get the sense working with him that that’s just not part of the scene. So we all get together and play good.

Did he give indications of what he wanted people to play?

Oh, no. The only thing he would say would be to the bass player, [John] Patitucci. See, the stuff is all worked out—it’s not a jam so much. I’m jamming, but you’re not supposed to. It’s all worked out. So he’d turn to Patitucci and say, “Here’s the line. It goes like this—for your information.” Then Patitucci would say great, jump in and play that line or a variation on it.

Most music in the world is not a jam. It’s not a jazz groove. It’s a worked-out series of parts, and then in there you can sort of take liberties and fool around. Now he’d didn’t tell me what to do, except for one tune. I was supposed to play this line over and over again, because I said to him, “Man, I don’t hear me in this.” But that’s because I usually just take it and put a flavor in there. But on one particular tune he did say, “Well, there’s a line you could play with,” but otherwise I was just sitting there trying to cop a feel.

Melodically, all that stuff is kaleidoscopic. It all works together, but it’s very cozy. It’s all inner-locking little things. Those are tunes, they have accompaniments. Like the calabash player [Hamma Sankare] is playing a particular thing. He’s not just wigging out. There’s a pattern that he’s supposed to play, and Farka Touré plays off of it. It starts with the calabash dude—see, everything’s built on what he’s up to, this funny triplet feel that he’s doing.

I don’t really understand the ins and outs of that music mechanically, because I was just in there with him for a couple of shows and then we sat in the studio and it would just unfold. We would all just play, which I’m used to doing, but I do know there’s a system to it that I’m just not aware of because I don’t know.

So his songs were set pieces.

That’s just what I’m saying. They’re supposed to be a certain way. But that doesn’t include me, necessarily, because how can I know? He’s not going to tell me what to play or tell Gatemouth Brown what to play. And hopefully you tear off a piece that’s good. But what he would say, which is very amusing, is “How long do you want it? Do you want four minutes of this, five minutes of this, or five hours of this?” And so he had inside his head a little internal clock that says, “Time to stop,” and he would just stop the song. But maintaining a kind of a sense of shape in there, that’s really not where they’re at.

In other words—intro, beginning, middle. They don’t shape a tune for dramatic purposes like we’re used to doing—you know, take me to the bridge, etcetera. They don’t have that. He doesn’t figure in that. He’s working it up—constant feel. And the tunes don’t have structure, like what we all assume. So what I did was cut tape a little bit, just to shorten them down. If they were at fifteen minutes, I’d maybe make them eight minutes, and get some events to happen. Because for our ears, even subtle events mean something—like every now and again, give me something. But he doesn’t care about stuff like that. I’m sure they stay up all night over there.

What are his body movements like when he plays?

Well, he rolls around like a sailor. He rolls—it’s real good. He’s very expressive, very good dancer, very graceful, and very “Mr. Macho Big Stuff,” I’ll tell you what. He really is, too—onstage in particular. Very, very good. Very charismatic. On the level of a faith healer. On the level of a shaman. But I really do think this guy knows a few things, because he’ll look at you and tell you something. And sometimes it’s a rather bizarre experience. He has a way of looking down into your throat in a funny way, even when he’s drunk, and knowing a few things. I think this guy’s got a lot of power.

And one thing about him, he wasn’t supposed to be a musician, he said, because that’s not his inherited job. Over there, your vocation is inherited. Even though, I guess, anybody could end up being a storyteller or something, musical jobs are inherited. He didn’t, but he had a talent. So being a very heavy individual, a very big ego, he went on with it. And he also does other things. I think he inherited the job of shoemaking and truck mechanics. And he went and did farming because he saw that there was a real need for food production. He’s very smart. He’s not some rustic, but he is a country man.

Gatemouth Brown sounds so good on viola. It was like an ancient voice coming out of him.

Well, Gatemouth didn’t know what the fuck to do. Gatemouth said, “Oh, man, this jungle music is out there, man!” You know how he’s kind of cross? So to him this music was like, “I don’t get the direction of any of this stuff.” I said, “That’s because it doesn’t have any. It just goes along.” He said, “Man, I can play any kind of music, but I got to understand the structure.” I says, “Well, play what you feel, don’t play what you don’t feel.” So he, being real good and real responsive, did great! He reached in and grabbed something great.

I think his electric guitar stuff is absolutely perfect. It sounds like some wigged-out guy in some township in 1960, and I think that’s just right-on, because Gatemouth is a natural guy. And hearing jazz sort of in a primitive way like he does, that Southwestern thing, is somewhere back there. It works. I mean, who’d have figured it? But of course that’s the beauty of all this.

The way we go about music is a great system, because we just say, “Hey, everybody play.” We all think nothing of it, right? The Western, American deal is to just jam and groove and dig it. Now, if you get the right people, you got something. If you get the wrong people, what you have is the typical junk. But in this case, this is all done lean to the bone. It’s all very, very good. And he is rhythmically strong, Ali Farka Touré. He’s rhythmically very powerful, so you don’t have to worry too much because you know it’s going to hang together.

When Touré plays the fiddle, how far back of a tradition is he reaching to?

Well, I asked him. He said it’s two-thousand-odd years. In other words, the life of the people. This is a basic, original thing.

Do you believe there are songs that have been handed down from the beginning?

That’s what he said. He said, “These tunes are old.” I said, “How old?” “These are two-thousand-year-old tunes.” I’m going, “Well, what was that then?” He said, “Well, that’s all medicine man.” It’s all like witch doctor music. He came to my house, picked up the fiddle, and began to play this real beautiful thing. All of them are not entertaining—they’re supposed to be original music.

They’re purposeful.

Yeah, yeah. So he says, “Wait a minute.” He’s stopped. He’s always speaking French. “Where’s the ocean?” I said, “It’s about two blocks.” Boy, he put the fiddle down and wouldn’t touch it. I said, “What’s the matter?” He said, “There’s a lot of spirit world in the ocean, and if they hear this and misunderstand, the ocean will come up and drown us right quick.” So I’m not going to argue with that. He’s not making a big thing of it, like “I have seen the vision” and being dramatic. He’s just saying, “No way am I going to play this fiddle two blocks from the ocean—period. Don’t ask me to.” “Okay.”

Then we got out in the studio in Hollywood, and he began to play a thing and put the fiddle right down. I said, “What’s the matter now?” He said, “There are too many doors in here. The doors are a problem.” I said, “Why? They’re big, thick doors. We’re all clean in here. What’s up?” He says, “No, there are a lot of people in this building. Somebody could go walking by inhabited by some bad spirit. If that door opens a crack, that spirit’s in here right now.” So I went around and closed all the doors.

But certain pieces he wouldn’t play, and certain other ones he would—that were less provocative, you know. But that’s where that instrument’s at. And I do believe if you were to listen to it from the standpoint of “do we hear blues in this,” you do. You hear bent notes. It’s like the guy that played with Charley Patton, sped up.

Henry Sims.

Exactly. I think that music is in there, and it’s a root thing. If you were really bent on research, you wouldn’t have too far to go. You would sit down and say, “Play me everything you know.” And he said, “If you come to Mali”—which he’s trying to get me to do—“there are other people who play and old men who know things and know the music and you can get off into it.” When people say blues to him, he gets pissed off and says, “That’s not what this is. This is our African tribal heritage. Calling it blues is your problem.”

To me, it’s like Lightnin’ Hopkins backwards. The way he plays, the way he looks when he plays, it all looks like Lightnin’ Hopkins on a real good day. A young Lightnin’ Hopkins, really deep. If you listen to those Gold Star [Hopkins’ late-1940s recordings for Houston’s Gold Star label], that’s what Ali Farka sounds like to me. But he doesn’t syncopate too much. It’s very simple rhythmically. There isn’t a whole lot of our Southern Black feeling of syncopation, which is quite unique. That’s where the question comes up, because it may be that this music, melodically and modally, is African. But the syncopation and the groove, like John Lee Hooker’s boogie groove—I don’t know, but that might be an American thing.

See, that’s where our mjusic comes in, because Ali Farka is not funky in the sense of Hooker, in the sense of that inside groove. He doesn’t play like that at all. He has none of that feeling, to me. I throw it across in there, because I know it’ll fit. If I can make it work, I like to hear the little boogie groove—such as I’m able to play it—up against what he’s doing. But like [Jim] Keltner noticed right away on drums, he says, “Man, that’s not where he’d really coming from.” Keltner could feel it immediately.

So I do believe that our so-called syncopation or our blues boogie thing—whatever you want to call that stuff, ka-chung, ka chung—if you write it out, it looks like dotted quarter notes or something. That may be where America kicked in. That’s interesting. I don’t think anybody’s talked too much about that, and Ali Farka’s not the only man in Africa. But they play so across the top. His groove is deep, but it is not deep in the sense of funk deep. See? So there’s a thing there that I haven’t really understood yet, because I’ve only played with him some. We’ve done now New Orleans together. We’re going to do some more shows. I may learn some. He says, “Come to Mali. You’ll hear a lot of good music.”

It would be real cool to go in there and look for where that funk thing comes from, because I don’t think anybody really knows. I’d like to take Bootsy Collins and some other people and go to Africa and see what the fuck’s going on, because I think that came from here. But you know me—I’m just a turnip truck driver from Santa Monica. I don’t necessarily have any real understanding of this stuff. It’s what you sense when you play with somebody.

Thanks, Ry. This is fabulous.

Well, go see him when he comes through.

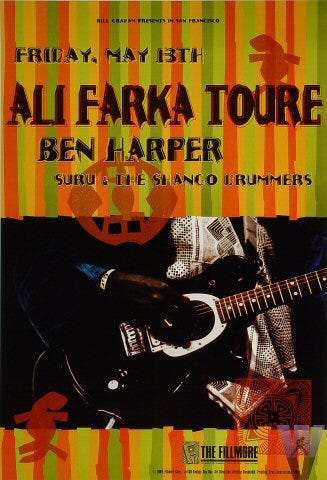

I’m going to see him tomorrow night for the first time, with Ben Harper.

Oh, he’s gonna be up at the Fillmore. Oh, I wish I could see that’s show.

Epilog

Talking Timbuktu garnered rave reviews and was awarded the 1995 Grammy for Best World Music Album. Ali Farka Touré released several more highly acclaimed albums before succumbing to bone cancer in 2006.

###

Related posts:

Listening to Slide Guitar Masters With Ry Cooder

Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown Interview: “Don’t Call Me a Bluesman!”

Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown at Aladdin Records

Lightnin’ Hopkins: “I Was Born With the Blues”

Ben Harper: The Complete 1997 “Will to Live” Interview

Help Needed! To help me continue producing guitar-intensive interviews, articles, and podcasts, please become a paid subscriber ($5 a month, $40 a year) or hit that donate button. Paid subscribers have complete access to all of the 200+ articles and podcasts posted in Talking Guitar. Thank you for your much-appreciated support!

© 2024 Jas Obrecht. All right reserved.

Beautiful!