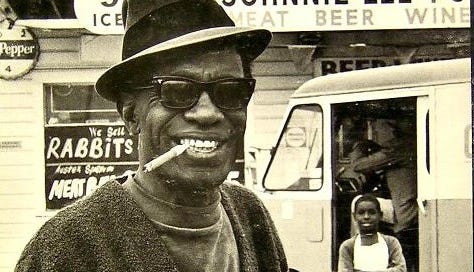

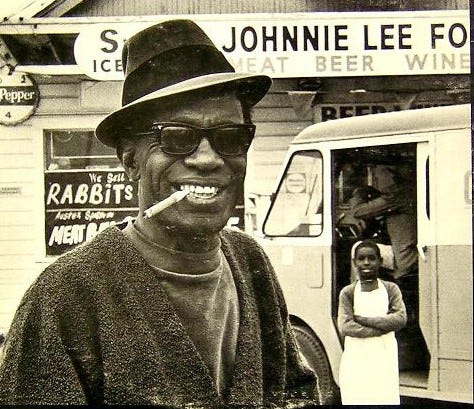

Lightnin’ Hopkins: “I Was Born With the Blues”

The Life, Times, and Breakthrough Album of a Texas Legend

“I had the one thing you need to be a blues singer,” Sam “Lightnin’” Hopkins used to tell his audiences. “I was born with the blues.” The songs he created – “barrelhouse,” he called them – were often as sorrowful as a cottonfield holler and as earthy as the Texas bottom lands that swallowed his sweat. “You know the blues come out of the field, baby,” Lightnin’ said. “That’s when you bend down, pickin’ that cotton, and sing, ‘Oh, Lord, please help me.’” Like Lead Belly, Muddy Waters, and others who’d worked as field hands, Hopkins parlayed his anger and pain into tough, deeply felt music. “The blues is a lot like church,” he explained in Living Blues #53. “When a preacher’s up there preachin’ the Bible, he’s honest to God trying to get you to understand these things. Well, singing the blues is the same thing.”

Born on March 15, 1911, Hopkins spent his early years in an East Texas farming community. “My family, we come up in Leon County,” he told Sam Charters during a 1964 recording session. “It’s just a little old country where they farm and raise cotton and corn and peas and peanuts, things like that. So that’s where I grew up to know myself – back out from Centerville about 12 miles back in the country.” Tragedy abounded in his lineage. His grandfather, a slave, had hung himself. When Sam was three, his father, a hard-drinking gambler who’d done time for murder, was slain in an argument over a card game. Sam’s older brother John Henry, ten years his senior, fled the area soon afterward, leaving his mother on her own to raise Sam and his siblings.

Before he was big enough to work in the fields, Hopkins was drawn to music. “I heard my brother playing a guitar,” he told Charters. “It was the first one I ever seen. He wouldn’t let me play his guitar. I wanted to play it, so at last one day they come in and caught me with the guitar ’cause I couldn’t hang it back up – see, I had to get in a chair to get it down. So he caught me fair. He said, ‘Boy, I done told you – don’t fool with that guitar.’ He says, ‘Can you play this guitar?’ I say, ‘Yeah, I can play it some.’ He said, ‘Well, go ahead, and let’s see what you can do.’ I went ahead and played him a little tune, and he liked it. So he said, ‘Yeah, he can play some. Where you learn that from?’ I said, ‘Well, I just learned it.’ So I went ahead and made me a guitar. I got me a cigar box, I cut me a round hole in the middle of it, take me a little piece of plank, nailed it on to that cigar box, and I got me some screen wire and I made me a bridge back there and raised it up high enough that it would sound inside that little box, and I got me a tune out of it. I kept my tune, and I played from then on. So I got me a guitar of my own when I got to be eight years old.”

Young Sam toted his guitar to a Baptist church social in nearby Waxahachie, where he encountered Blind Lemon Jefferson for the first time. Albert Holly, a blues player who came around to court his mother, inspired Hopkins to sing. Sam played leads alongside his brothers and sister in their family band and gathered with them around the organ to sing “them good old Christian songs.” During his teens Hopkins played with a fiddler, serenading and passing the hat. “When I got good, I went to find the places where they’d barrelhouse at,” Hopkins recalled. “I didn’t know – I just had to wander up on them places around Jewitt, Buffalo, Crockett. They had little old joints for Saturday nights, you know.” In 1927, Hopkins began playing area dances and juke joints with his cousin, blues singer Alger “Texas” Alexander, who’d just done his first session with Lonnie Johnson on guitar.

Hopkins spent most of his time, though, chopping cotton and driving a mule. “It was hard times,” he told Charters. “I was trying to take care of my wife, me, and my mother. Six bits a day – and that was top price. I swear, I would come in in the evening, and it looked like I’d be so weak till my knees be cluckin’ like a wagon wheel, man. I’d go to bed, and I’d say, ‘Baby, I just can’t continue like that.’ Look like no sooner than I go to bed and I’m ready to go catch that mule again.” Eventually the hard-drinking Hopkins got into fights that landed him on a chain gang: “I had to calm down. Man, that ball and chain ain’t no good for no man. From the ’20s up until the ’30s I was doing that. Getting cooped up and whomped around pretty good. Somehow or another, I’d always be lucky and managed to get out.”

Hopkins made the 120-mile journey south to Houston for the first time in 1934 for a radio broadcast with Texas Alexander. He moved there for good a few years later, living in rented rooms, taking on odd jobs, and playing for tips on city buses and in establishments along Dowling Street. Word of his performances reached Lola Anne Cullum Allen, a talent scout who arranged his November 1946 debut session for Aladdin Records. Pianist Wilson Smith accompanied Hopkins on the drive to Los Angeles, where they recorded together. “Boy, we tore the joint up,” Hopkins exclaimed. “And so they named me ‘Lightnin’’ and named him ‘Thunder.’” Hopkins’ first release, “Katie Mae Blues” backed with “That Mean Old Twister,” sold well and brought him better-paying gigs around Houston. His second Aladdin session, held in Los Angeles nine months later, yielded another classic, “Short Haired Woman.”

Jumping from label to label, Hopkins recorded prolifically during the next eight years, cutting nearly 200 selections that would eventually come out on Aladdin, Imperial, Gold Star, Modern, RPM, United, Kent, Crown, Decca, Verve, Mercury, Mainstream, Arhoolie, and other labels. Many of these recordings display his genius for improvised poetry as he created new verses or entire songs as the spirit moved him. He could sing about hairstyles, being broke, how his car was running, goings-on in a club where he was performing, or the way things used to be. Frequently referencing himself in his lyrics, he sang “Poor Lightnin’” into an everyman of the blues.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Talking Guitar ★ Jas Obrecht's Music Magazine to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.