Listening to Slide Guitar Masters With Ry Cooder

In 1992, Cooder Shared His Views on Ten Classic Blues

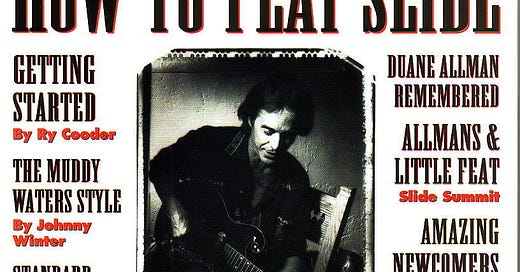

In August 1992 I journeyed to Ry Cooder’s home to interview him for a Guitar Player magazine cover story. We were scheduled to spend several hours together, so in addition to my recording gear and list of questions, I brought along a cassette of ten stellar slide guitar recordings. Cooder, after all, is one of the world’s foremost bottleneck players. If we had the time, I figured, it would be interesting to hear his take on each of these songs.

Ry was amenable. We began with one of the most visceral postwar Chicago slide recordings, the Baby Face Trio’s “Rollin; and Tumblin’, Part 1.” Recorded for the small Parkway label in January 1950, this song features Little Walter on harmonica and Muddy Waters on slide guitar. Ry’s comments began while the song was playing:

Ry Cooder: “People have suggested that Little Walter is the greatest blues player on any instrument, and I’m inclined to agree. It’s just his time and his touch. The most elegant blues. The rhythm is just awesome. Muddy Waters on slide! He always played the same way; it always sounds the same. Fucking great! Jesus! [Turns off tape.]

“To me, that’s an example of somebody who transcends anything we think we know about the guitar. I mean, it could have been a one-string there, a post with a string, any of my guitars—it wouldn’t make any difference. The guy’s just playing on two strings, like the D and G strings, so that tuning must be G [open-G].

“When guys play like that you don’t feel frets and six strings and a scale length. It’s beyond construction and principles. He’s playing where he knows the notes are, and they are locking into this spirit thing of playing, the movement of the song. And he goes past the note—the note isn’t just here [points to a fret on his guitar]—because there are degrees of the note. It’s like Turkish music in some ways—there’s 5,000 notes. The great thing about this is it liberates you from these idiotic frets.

“That’s where all those old guys hear that stuff. There are nuances—no phrases come down the same. When you need a lift, you go sharp, and when you need to sour it up and make it feel a little darker, you go flat. But you don’t think about it. You just do it.

“It’s staggering to have that quality of a performance on a record, though, knowing what we know. Listen to Sonny Boy Williamson’s ‘Little Village’ with Leonard Chess—how do these records ever get made when assholes like that were running the show? It’s amazing to me. They made these records under such duress, conditions that ultimately we see around us today. They talk about slaves singing code songs—it’s hardly any different now.

“But the really amazing thing is that you can get that kind of free expression and excitement and even joy, perhaps, in a white guy’s recording studio. It takes a lot of power and amazing strength of personalities. These aren’t wimpy guys. They’re heavy-duty characters, and it’s coming out. They’re just blasting away. We’re very lucky this stuff got recorded at all. It’s a miracle that it did.

“[Restarts tape.] It’s not chord-based. You don’t feel chord in this. It’s greater than anything African. This is taken to another planet. This is the beauty of American music. Listen to those big string bends—whoa! Slap bass. It’s incredible. Nobody in Africa can do that. I mean, as great as African music is, it all comes together in this country.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Talking Guitar ★ Jas Obrecht's Music Magazine to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.