Welcome to my Talking Guitar podcast. This two-part episode presents a rare interview with Irish guitar legend Rory Gallagher. At the time of this conversation, I was an editor for Guitar Player magazine. I’d also been a devout fan of Rory’s music since the early 1970s and had collected all of his albums, so I was excited to have an opportunity to speak with him at length.

Our interview came down on the afternoon of March 15, 1991, when we met backstage at the Catalyst Club in Santa Cruz, California. Rory had just released his final studio album, Fresh Evidence, and was midway through what was to be his last American tour. As we began to talk, I was delighted to discover that Rory was insightful, self-effacing, and down-to-earth – just an all-around sweet guy. He displayed an extraordinary knowledge of historic American blues musicians and was refreshingly candid about his recordings, playing techniques, guitars and gear, the personal issues that had prevented him from touring overseas, and his advice for staying sane on the road. Now, on to the interview….

****

I really like your new record. One of the things I admire about your playing is that you’ve stayed true to the music that inspired you in the beginning.

Yeah, I think that you have to recognize the kind of source point that you have. Even though you develop as a player over the years and you get influenced by different things, you have to keep to the heart of what you started with and that kind of initial vision of music, you know? Obviously, it’s taken me this amount of time to learn a lot of different things about music and playing and so on, but I think I’m getting there slowly. [Laughs.]

You seem to gravitate toward roots American music throughout your career.

Yeah. Even though I grew up in Ireland, where there’s a lot of folk music and traditional music is very close at hand, it didn’t initially appeal to me, even though I can see traces of it creeping in over the years in my songwriting and some chord patterns and some kinds of solos I do. But I wasn’t really turned on until I heard American music via Lonnie Donegan. You know, I heard him doing Woody Guthrie songs, Lead Belly songs. And of course, I heard Elvis Presley, Eddie Cochrane, the early rockers, Chuck Berry. So it was a mixture of folk, blues, and rock from America. I was only six, seven, eight, nine, at that age, and then I just followed it through and learned about all these artists. And I’m still discovering undiscovered people and learning. But it took me about a good ten or fifteen years to find out who was who in the whole spectrum of things – who were the originators or the prime movers, and who were the followers and copyists.

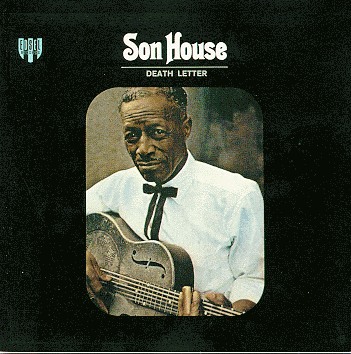

For young players who aren’t acquainted with Son Houses of the world, are there records you’d recommend?

Well, I mean, everyone is stating the obvious Robert Johnson connection. He seems to be the virtuoso of that era, of that point, but Son House would be very important inasmuch as he gave lessons, I believe, to Robert Johnson. He probably wrote “Walkin’ Blues,” for instance. And Muddy Waters also claims that Son House was important at the time.

It depends. You see, it’s very hard to dictate to some youngster. They might listen to Albert King and immediately see themselves in that lineage. I think all young players, rock and blues players, should dig deeper, back beyond the obvious big blues stars like B.B. King and Buddy Guy, who are all great. I’m very interested also in the country blues and the “electrified country blues,” as I would call it – Big Joe Williams and things like that. I also like all the slide players from Earl Hooker through Muddy Waters, obviously. Robert Nighthawk is a favorite of mine, and I eventually discovered Tampa Red kind of late on, and he’s very smooth-playing. Like that lick that Muddy Waters is known for – we all thought that was an original Muddy Waters thing, but he got it from Tampa Red. So this folk music tradition of passing on and picking up and stealing goes on like mad, you know.

But in my own style, being a European very influenced by American music and so on, I try to find a way that if I’m doing a blues number, I can do it very traditional if I want to. I can also add my own element or my own twists to it and have it be a rock song with a blues thing in it. I try to be adventurous and progressive in some material, in others I try to be as downhome and ethnic as possible.

We hear that on your performance of [Son House’s] “Empire State Express.”

Yeah. That was as close to . . . I did that in one take, on purpose. I did that on St. Patrick’s night, oddly enough, just last year. It was the last track on the album [Fresh Evidence], and I loved the song. I’d lost the [Son House] album that I had, so I had to remember it. Luckily I had written the lyrics down. I do it close enough to Son House’s style. To sing it in the tempo I was doing, I had to slightly adjust the rhythm a bit, but I thought it was great song. I thought it was a very overlooked song, you know? Al Wilson of Canned Heat played a National guitar on one or two tracks of that particular album.

That’s Son House’s Death Letter record?

That’s right – with “Pearline” and “John the Revelator”— that’s another great song on that. And then “Ghost Blues” [on Fresh Evidence] – that’s quite traditional in its approach with the Dobro, or National. The mood also on – what do you call it? “Middle Name” – the guitar on that is more like a Slim Harpo record. So it happens, all kinds of references all over the place. There are a couple of rock tracks alright – “Kid Gloves, “Slumming Angel,” “Walking Wounded.” The rest are very much in the blues field, I think. “The King of Zydeco,” even though it’s about Clifton Chenier, it’s almost countryish more than zydeco in the feel, but by the time the accordion comes in and the maracas, it is . . . We did try the washboard on it to see if it gets it – you know, his brother’s “rub board,” as they call it – but it didn’t work in that song. We laid down another track, called “Never Asked You for Nothin’,” which nearly made it to the album, but it’s one of those fifteenth songs that would crop up again, you know. And we were lucky enough to find this guy, Geraint Watkins, who’s an enthusiast of Cajun music and zydeco music and plays great boogie-woogie piano and rock and roll piano. He’s played a lot with Dave Edmunds and he’s played piano with the Stray Cats and so on, and he has his own group called the Balham Alligators. Balham is an area in South London, so it’s a bit of a funny name, really, just a ludicrous name. That’s the way he is.

Also, production-wise, I was very keen on the album before, which was called Defender, which had a lot of blues elements in it as well, but it’s more of a rock production, whereas this [Fresh Evidence] is kind of – not mellow, but we didn’t overdo the compression and we didn’t overdo the cleaning up and the noise gates and things like that. We left it fairly wooly and casual, which is the way I think suits the songs, you know? I hope people catch up on Defender, because that’s an album that’s still quite current in the set, even though we move the repertoire around every night.

What year was Defender? Two years ago?

Two years ago.

It was released in England?

Released in England and all over Europe. It will be released here in two weeks’ time, in fact, so it will be running concurrently with this new album. But obviously the emphasis is on Fresh Evidence.

Defender has more of a rock stance?

Rock songs, some tough songs like “Kickback City” and “Road to Hell,” but there are some blues songs. Like, one of the numbers we do is called “Continental Op,” which was influenced by Dashiell Hammett – that’s one of his characters. Even though it’s a rock boogie feel, it’s very much a John Lee Hooker chording, with suspended fourths and things like that. It also had a song called “Loanshark Blues,” which was there again a bit like a Slim Harpo “Shake Your Hips” type of feel to it, but it had some nice lyrics about a down-and-out guy in debt to the loan shark – very fast, alliteration-type lyrics. There’s a song called “Ain’t No Saint,” which is very much an Albert Collins-Albert King feel. I’d like to get to the point where it will be a Rory Gallagher feel rather than…. But you have to refer to all these inspirers or influences, you know.

Although there is definitely a certain Rory Gallagher feel. “Slumming Angel,” “Living Like a Trucker” – there’s a continuum between those songs. “Living Like a Trucker” was one of my favorite songs in school.

I remember that one quite well because we had the clavinet with the wah-wah. I was so straight-laced then, I wouldn’t play a wah-wah pedal myself. It’s like somebody joked to me the other night – they were disappointed to hear certain equipment I was using. They didn’t even want me to use electricity. Some people have this image of you as so purist that you wouldn’t even use…. you know [laughs].

They’ve obviously never heard Taste at the Isle of Wight.

Right. But this is the way it goes. But “Living Like a Trucker,” I like that track myself. All those albums will come out in the next year or two on IRS on CD, with lyric sheets. And some will be slightly remixed and EQ’d and things just for CD. With this absence behind me, it’ll be great to have all my old material out again and people can look at it and see if it’s held up in court or if it’s not. I think it hasn’t dated too badly.

Blueprint and your live record – all that will stand well.

That’s good.

When you’re recording solos, you definitely have your own style and sound. What do you expect from yourself? What should a Rory Gallagher solo be about?

I try to split the difference between being fairly clever and technical, and still primitive. Because I think if it’s just a technical exercise, that’s all very well. Even if a solo has to lean towards the primitive, so be it. It depends on the song, if you have to play very calculated or if you’re overdubbing the solo, sometimes…. You know, I used to always go for live leads, mistakes and all, just for feel. But now I’m prepared if a certain song needs a very melodic type of solo, I’m prepared to work on it over and over. But I try not to get in the habit of dropping in [punching in notes] because it’s very tempting to get the perfect solo. I have been guilty of it once or twice [smiles], but only just to save it if you’re in a great direction. But as a rule I try and keep a grip on technology, so it doesn’t take the human factor out of it and you get too lazy about things, you know.

Has technology impacted the way you make records? Was recording the new album different than, say, recording Blueprint or Tattoo?

A little bit different, yeah. Of course, we’ve got the 24-track now. Both of these albums were 8-track. When we went 16-track, I thought that was the year 2000! In fact, on this album we brought in tape echoes, spring reverb. We tried to use more vintage equipment. We did use, obviously, certain modern EQ’s. I’m not that mad about digital equipment, and obviously if you had to clean up something, you would use a noise gate – you know, very subtly. But performance-wise, I don’t think there’s that much difference, except that we probably were a bit more rigid in those days about getting it. We still try to get it in the first take. I would repair something now if I thought it was a great performance, whereas in the early days, I’m sure that just because of a repair we could have saved some tracks, but we were very keen with getting it as-was, even with the Telecaster whistling and everything. It was a ridiculous kind of attitude, but that’s the way I thought. We needn’t have been so strict with ourselves, but that’s the way we were. I had the same attitude to echo, as well. I was very conservative in that area, which probably was a mistake. But you learn as you go along. It also depends on the engineer that you’re working with and the confidence you have in him and the whole sound and feel. I still think the approach for performance isn’t that different from the early records, but we’re probably a little more aware of what’s sonically possible now and what we can do. And also all those early albums were done in three to six weeks, whereas albums now take six months, nearly, this album, between remixes and retakes and what have you.

Did you tend to try to avoid layering tracks and go for live as much as possible?

Yes, in general. I also went for a strong rhythm guitar part in tracks like “Middle Name” and “King of Zydeco” and “Walkin’ Wounded.” Instead of the Strat, for instance, I’ve got this small Chet Atkins Gretsch, which is great for rhythm with fairly heavy strings.

6120?

Not the Eddie Cochrane model, the Les Paul-shaped one, the little orange one. And that was great for rhythm. And I used a Les Paul Junior on the rhythm part of “Kid Gloves” and also the rhythm part of “Walkin’ Wounded.” Even though I’m identified with the Strat and I like the Strat, I think if you have Strat rhythm and Strat lead, except in a Hendrix situation, it can be a little bit one-dimensional. So it’s nice to have an alternative guitar to broaden the sounds. Even a Telecaster sounds good for rhythm and then Strat for lead, depending on the track.

Do you still have the old Strat that you used on all those records?

Yes. It’s super-glued together now.

Like Albert King’s has just been super-glued back together, his Flying V.

Great.

His bus flipped over, and it landed in a river.

With them all onboard? With the band onboard as well?

Yes. He wasn’t hurt at all – it was just his equipment.

I always like the out-of-phase sound he had, but he would never give you any information about his tuning or anything. Also, he was one of the few bluesmen that I know that was using Acoustic transistor amps, solid state, which had a distortion control on them. Steve Winwood used to use one alright when he was with Blind Faith. And I think on the Gary Moore album, when Albert was working on it, he was actually playing through a Roland JC-120, which is a transistor. So obviously he’s at home with them. But then the pickups on the Flying V’s are very full and warm, and they can take the match-up with the solid state.

It’s funny. When Albert sent the guitar to the guy [Dan Erlewine] to get it repaired, he put it in a burlap sack without a case, wrapped some rope around it, and sent it by Greyhound bus.

God almighty!

The guy asked Albert why he did it, and he said it was too good a case to risk having anything happen to it.

[Laughs.] That’s funny.

That’s Albert.

That’s strange. That’s like the story of Mike Bloomfield showing up to record with Bob Dylan with the Telecaster without a case, in a zipper bag. That casual thing is great, you know. Everything’s gone into flight cases now. But we still have a few funky areas left in terms of cases. But the more you travel around the world, you really have to be cautious of your instruments, because it’s only when they stolen or they get broken that you really miss them at that particular show.

Have you lost instruments?

We’ve lost a few. No, I did actually have the Stratocaster stolen in Dublin in the ’60s. I got it back after two weeks because they had a police program on TV and they put it on there. I lost a Telecaster at the same time – somebody broke into the van and stole the Strat and a Telecaster, which was only on loan to me. That never came back. But I got the Strat back. It was found over a ditch, with a few extra scratches from the brambles and things. It had been out in the rain, as well. So I swore I’d never sell it or paint it after that. I had to borrow a guitar to get me through that fortnight. I had given up hope in getting it back, to be honest with you, and I really couldn’t afford another Strat at the time. I was playing a Burns which a roadie had leant me. But that’s the way it goes. But it’s [the Strat] playing well. Obviously, machine heads, frets, pots, and things have been changed over the years, but it’s still the same.

Do you know the year it was made?

It’s November ’61, and I got it in August of ’63. So it was second-hand. It was the first Stratocaster in Ireland, apparently, but the guy who ordered it wanted a red one, like Hank Marvin, and they sent him a sunburst one instead. So he had to wait for a year-and-a-half or whatever to get the red one, and then he sold this one through the shop. So I got it. Prior to that, I had loan of a guitar. I had one electric Solid 7, which was an Italian, very flimsy guitar, which used to distort and everything through this four-watt Little Giant amplifier I had. I wish I had it now as a tune-up amp, because it was like a Pignose type of sound. In those days, you were trying to get the clean sound of Hank Marvin and the Ventures, or whatever. Buddy Holly. But when I got the Strat, I was set.

It must have been a happy day for you.

Oh, it was. I mean, for weeks, every morning I would wake up, I’d go over and look at the guitar in the case, and treat it like a living being or some kind of magical thing. Even the smell of the case – I mean, [smiles] I was really standing on my head at that time.

Do you still travel with it?

Oh, I do, yeah. I don’t necessarily carry it myself on the plane, but we’ve got it taken care of. We watch it. Luckily, I have a ’57 as well, which is in great condition. I got that from a guitar player called Robert Johnson, of all people.

From Texas?

Actually, he’s based in Memphis, or used to be, and he worked with John Entwistle and so on. I got it through him, and it’s a great guitar. I use that on the albums when I don’t use the old Strat. It’s more a Fifties sound – it’s more of a clean, rockabilly, Buddy Holly sound. Let me see. On the record I used it on – I can’t remember off-hand. Sometimes it’s a little more, because of the maple neck, zingy. Because my old Strat is a classic Strat, I suppose. Because of the age and sweat in it and everything else, the tone is a lot dirtier, raunchier, than your standard Strat. It borders on the sound of an SG almost, sometimes, I think, or a real raw Tele, which suits me. But the ’57 is nice. All I’ve done to that was I put the big frets on – I like the jumbo frets. And I also disconnect the middle control, which is the tone pot for the rhythm pickup. So on both Strats I have the lower tone pot as a master tone. I like that on a Telecaster. You can adjust the tone on the lead pickup. But I think the idea that Fender had was that in those days you played rhythm on the rhythm pickup and then you clicked into the “Peggy Sue” position and went for it. In the early days, you see, some bands didn’t have bass or bass guitar, as you know. The same with the Telecasters – in the rhythm position, that big capacitor creates big, boomy bass lines. In fact, Muddy Waters, up until a couple of years before he died, he left his guitar in that style, so he could great that real boomy rhythm thing, you know.

Muddy played that Tele to the very end, as far as I know.

The red Tele. Apparently the neck was a replacement neck. The guitar was originally white, or blonde, and Fender of Chicago – there must have been a branch there – gave him a neck with an extra-thick back to it, so that’s what happened there. But Muddy had a great feel. Even when he wasn’t playing slide, the figures he would play – particularly with Jimmy Rogers and, of course, Sam Lawhorn, who just passed away fairly lately.

Six or seven weeks ago, was it?

That’s right.

You were lucky to have gotten to work with Muddy.

I was, yeah. Haunted. Originally Al Kooper was going to produce that album [The London Muddy Waters Sessions], and he made the call. They changed producers then, and the project was back on. But I was obviously delighted. It was three nights. I was playing every night, gigs, at the same time, and they would hold up the session till midnight till I got there. And he was sitting there tuning his guitar, a glass of sparkling wine in his hand. He handed it to me, treating a 23-year-old youngster. But, I mean, it was serious business, because he had half his own band there, and then he had Mitch Mitchell on drums, Steve Winwood on piano. So we had a good time. They remixed it back in Chicago, I think. They brought a few spare tracks from it out on some of these compilations or these best-of series.

What was it like working with Albert King [on his Live album]?

The situation was, he showed up in Montreal. It was all arranged to be recorded, and his second guitarist left him on the day, so they asked me would I stand in? He asked me himself. I said no, because his material is quite arranged – it’s not loose like Muddy’s, you know? He’s a more intense guy than Muddy, I thought, not as friendly. I hate to say it, but I was forced to sit in and just fill out as best I could. There was no rehearsing, no nothing. You just had to guess what chord, what key he was in. Any time I’d ask him what key it was, he’d say “B natural,” and he’s playing in minors. His tuning is like Em6 or Em7, as far as I know, back to front, so I just had to busk it. But it was an experience! I got over it.

I heard Mike Bloomfield say something really telling once. He was talking about being onstage with Hendrix, and they were having at it a little bit. He said Jimi just pulled out all the stops. They way Mike told it, it was bombs exploding and World War III. He said, “All I could think was, I wish to God that I were Albert King!”

Yeah.

What a compliment.

If Albert wants to nail you to the wall, he’s got that amazing attack. He just hits that one-single-note-type syndrome. I was a Hendrix fan and a Bloomfield fan. I met Mike once – we did a TV show, Midnight Special, when the Electric Flag reformed. And he was a very nice, modest guy, and a beautiful player. A really soulful player. I could see him in a situation with Hendrix where he wouldn’t go into that trickery, really. But it’s a compliment to Mike if Jimi was that scared, because normally Hendrix was quite prepared to lay back and even play bass on these jam sessions.

This was onstage in New York.

Probably at The Scene club.

Had you met Jimi?

I never met him. I saw him playing two times, but three shows, if you know what I mean. I was in the Speakeasy Club in London once, and he was sitting a couple of tables away, talking to someone. I hadn’t the guts to go over and annoy him. That’s happened to me a few times. And you regret it later – I mean, all you got to do is shake their hand and make contact. Because these people pass through this world and you don’t get to say hello to them, you know.

If you could somehow transcend time to see any musicians play, who would be tops on your list of people you’d like to have witnessed? Living or dead.

Oh, there’s a whole glut. I’d like to have seen Django Reinhart live – I believe that was scary. Obviously I’d like to have seen Robert Johnson – who wouldn’t? Oh, I don’t know. I’d like to have seen the first Sonny Boy Williamson. There are so many people. I’d like to have seen Buddy Holly live, as well, for that matter. I didn’t see Son House live. I was lucky enough in the ’60s I saw a lot of the main people. I saw Muddy, I saw John Lee Hooker, Big Joe Williams. I saw T-Bone Walker. And we were lucky enough touring the States we played with Freddie King, we played with Juke Boy Bonner. I’d like to have seen Blind Boy Fuller live, mind you, although he was in the line of Blind Boy Blake. And I saw Gary Davis. I’m pretty lucky, really. But certainly some of the early people I’d like to have seen.

Blind Boy Fuller is a fairly obscure figure, even today. How did you happen to come across his music?

The Blues Classics record with Bull City Red on it and Sonny Terry.

With “Step It Up and Go” on it?

Yes, and “Three Ball Blues.”

Wasn’t he a wonderful player?

Oh, he was great, yeah. And Scrapper Blackwell I liked a lot, particularly when he recorded when he was about 71 or something like that. And he was in great form. In fact, when I went back and listened to the original recordings with Leroy Carr, I was slightly disappointed because he had actually improved, to my ears, as a player. But then the early records were recorded very dull – you couldn’t hear the guitar that well. That was a surprising thing about that blues revival, that Furry Lewis, John Hurt, a lot of them. They’d improved as opposed to going the other way. You know what I’m saying? It was fantastic.

Especially Furry. His slide playing got so magnificent when he was older.

Yeah. There’s a lot of people still alive. I hope now that John Lee Hooker has this big hit and that Albert Collins and Albert King are doing well, and B.B. King, that it will draw in some of the more less-known guys, like John Littlejohn and Johnny Shines, Johnny Young. They’re not the classic players, but they all have nice rough sounds, I think.

Honeyboy Edwards is still getting gigs.

Yes, yeah. Where’s he living now?

He’s living somewhere in Ohio.

Is that right?

In fact, I might have his address in my briefcase there. I have Johnny Shines’ address. He’s a sweet old man. He had a stroke. He can’t play real well, but his voice is the best Delta voice I’ve ever heard in person.

Yeah. I’m not surprised. That’s some project you’re on. You’re doing something I should do, really. [Here Rory is referring to the research I’d been doing for my book-in-progress Early Blues: The First Stars of Blues Guitar.]

End part 1. This conversation continues in Rory Gallagher 1991 Interview, Part 2

Thank you for supporting independent music journalism!

© 2022 Jas Obrecht. All right reserved.

Share this post