Do you use open tunings?

Yeah. I use the DADGAD tuning on “Out on the Western Plain,” the Lead Belly song. That’s one of my favorite tunings. That was supposed to be discovered by Davy Graham, a Scottish guitarist, and then it was used a lot by Bert Jansch and Martin Carthy, all great players in their different ways. I’ve been messing around with dropped D lately, which is taking down the bottom D and the top D. It’s quite nice. Open A is related to open G, and I use that a lot as well, putting on the capo.

What did you use on the record for the slide tunes?

Let me see. Open G. Even though “Ghost Blues” is in A, the guitar was tuned to G. The slide on “Walkin’ Wounded” is just in standard tuning, which I can do. “Empire State Express” is open G. I think any other slide parts are all in standard tuning, in the same way in which Earl Hooker could play chords and then go into the solo.

Muddy told me that Earl Hooker was the guy, the best [slide player] that ever was.

He used to play great single-string guitar too, particularly on the early Junior Wells records. On the original “Messing with the Kid,” he plays great slurpy Stratocaster sounds, before he went off to the Danelectro. And then he went on to that Gibson.

His slide on songs like “Anna Lee” is just out of this world.

“Anna Lee” and “Sweet Black Angel” are both, as you know, Robert Nighthawk songs. But he was the first guy, aside from Hendrix, that I could accept the wah-wah pedal from [laughs].

I had trouble with Earl’s wah-wah – sometimes he went overboard.

Yeah, yeah. Well, I think what turned a lot of people was the Howlin’ Wolf record where they added so much wah-wah pedal – remember that one that came out around the time as Electric Mud? [The Howlin’ Wolf Album, on Chess]

The one with Pete Cosey on it.

Yeah. I can’t remember who else was on the album. The liner notes were funny. They even put on the front that “Howlin’ Wolf doesn’t like this record, but then he didn’t like his electric guitar ….”

That was a great record.

Yeah.

We interviewed Pete Cosey, who played on Howlin’ Wolf sessions and played some stuff with Miles Davis too.

Oh, really?

And there’s a quote that he said that when he showed up for the session he had real long hair and a beard, which was unusual for a Black guy in those days. And Howlin’ Wolf said, “Why don’t you throw all that wah-wah and shit in the lake on your way over to get to the barber shop?”

Ooh.

That’s how he met the guy. [Howlin’ Wolf’s longtime guitarist] Hubert Sumlin was really underrated.

Absolutely, yeah. It’s a shame.

He’s trying to make a comeback. He’s in Wisconsin.

How is his health? Is he okay?

I’ve heard he’s feeling good lately.

Yeah. He’s made some records that I’ve got since the Wolf days, but he’s either produced the wrong way or the material’s not there or he misses Wolf or all the chemistry that went on.

Hammond Scott and those producers have him with their house players. Hubert should be a guy who’s allowed to pick his own band and do his own material his own way.

It’s important, really.

It’s too generic otherwise.

Well, a lot of people think they know best, once they get this producer mentality. I know it’s an important job, but some people can be extremely unsympathetic to what’s right, you know what I mean? But then as the years move on and on, everything becomes tighter in terms of budgets, P.R., pressure, and all these other factors. Hubert’s a guy who deserves his hour in the sun, really, because he played some amazing stuff, really, both on the Les Paul and on the Strat. You never knew which guitar he was playing on the records – he’s got a great sound! And then he showed up in England with this tigerskin-type Strat. I saw a photograph of it on one of those Kent albums of Memphis blues – all that Joe Hill Louis type era. But there’s a photograph of the guitar, and I have a vague idea it was an African guitar. Somebody told me it’s called a Zanzibar or something like that. If you ever see him, ask him. Particularly with all this interest in all these pawnshop specials, this one has never cropped up – unless he painted it himself or something.

That could be. Hubert is such a gentle guy.

So I believe. I never met him.

Always has a kind word about everybody.

Yeah. That’s good.

When you’re playing slide, do you use a guitar pick?

Yeah, pick and fingers, you know. I also vary the slide. Sometimes I use a Coricidin bottle on my ring finger, sometimes on my small finger. Then sometimes I use a brass slide if I’m playing the National. But if I’m playing the straight electric, I use a steel bottleneck.

Do you hear a difference in tones between the various materials?

I do, actually, yeah. The glass is obviously more – I won’t say Hawaiian – but more smooth and sweet. The brass or copper is very harsh, if you want to get that Son House sort of attack. It’s almost too harsh all the time. Steel is a good compromise. It depends on the guitar you are playing.

Do you use a socket wrench like Muddy, or a steel slider?

A steel slide. I have a socket wrench because John Hammond told me he was using a socket wrench, and then Lowell George, who we played with, had one as well. They’re fantastic, but you really need very heavy strings for them. I don’t know which one I have – a 5/8th or 7/8th or whatever it is. They’re fantastic, but if you’re playing more than a couple of numbers, they do wear your small finger down. They’re very heavy, but they’re ideal for slide. That’s my one complaint – not that I like light slides, but you don’t want them to be tiring your hand.

Do you set up your action differently if you’re going to play slide, or do you have a special guitar for it?

I have a Gretsch Corvette which is in open G or open A, depending on the song, and that’s got strings from like .013 to .050, something like that – medium. My regular strings would be like .010 to .044, something like that, and the action is quite high. So it’s okay for slide. But if you want to play real open-tuning slide, you need the heavier strings. But I can cope with both, you know. I try to, anyway. [Laughs.]

What is your favorite amp?

Good question! It’s a battle between the Vox AC30, which is my first amp, and the 4x10 Bassman Fender, although I love the little Deluxe Fender, which is nice as well. But I have played Ampeg VT-44s, which are very nice. Over the years I’ve used Marshall 50-watt combos in conjunction with a Fender or a Vox, and they’re very good for volume and bite. But the warmth of the Fenders and the character of the Vox is pretty hard to beat, so it’s somewhere in there.

What do we hear on the record?

On the rhythm tracks it would be a combination of Vox and Marshall. Nearly all the lead parts were done with the Fender 1955 Bassman. We took the back off it and put mikes in the back as well as the front, so we got all kinds of variations. That was pretty much the way – I mean, not every track was laid down as a rhythm track, but I’d say 80% of the tracks were like that – Vox and Marshall for rhythm, left and right, and then the Fender Bassman for leads.

We’ve been waiting for you to come through [tour the United States] for a long time. What’s been the delay?

I don’t know. We just went back to Europe after the last American tour, in ’85, and we just got stuck in Europe, recording and touring. We played in Yugoslavia and Hungary and so on. And then we were trying to sort out the right record deal in America. I don’t know where the years went.

We’d see ads in N.M.E. that you were playing over there.

We just got irritated too. We were on a couple of big nationwide tours with these big, stadium-type rock bands. We’d do that in order to get to America, to pay for the flights and also to give us some free time to play clubs and colleges. But doing these others gigs, you’d go home feeling dissatisfied, because you’d be badly treated in some cases with monitors and amount of stage room and lights and stuff.

Time onstage.

Time, indeed.

American audiences aren’t always kind to opening acts, especially if it’s a different genre.

Indeed! And that was the problem. It wasn’t so bad when we were on the same bill with, say, ZZ Top or somebody in that line. But then we happened to be on a couple of bills that were totally alien to our kind of stuff. We weren’t booed or anything, but you felt you’d wasted a couple of weeks of your life when you could be playing clubs or small theaters or whatever. I regret we didn’t come back in the meantime, but it gave us a chance to reassess what we were doing and we got very busy in Europe and so on. And then I developed a flying problem, as well, to make matters worse.

Fear of flying?

Yeah.

I read that in the L.A. Times.

Yeah, I had a couple of bad flights and I got my Buddy Holly complex. It got so bad, I couldn’t even fly to Ireland, which is only an hour away [from London]. Then to play on the Continent, I would have to fly out the night before so I’d be okay on the date.

Would you get really nervous?

Yeah. It was not so much a fear of death thing. It was a mixture of claustrophobia and a few other things. This is a miracle – I flew from London to Tokyo, Japan, to Australia, Australia to L.A., L.A. to San Francisco, and so on. We’d have to make our way cross country and then back to London. So far, so good. My prayers have been answered, then. To beat that flying phobia was quite an ordeal for me, I can tell you, because it’s the last thing I needed after all those years of touring and flying two times a day. So that compounded my problems of not being able to get to the States.

Do you have advice for keeping your sanity while you’re on tour – keeping yourself centered? It is a rather unusual life.

It is, indeed. There’s also a terrible danger – between travel and other things and getting to the gigs and so on, you get little time to play on your own in the hotel, and you can get lazy about playing. So I make a point of playing every day in the hotel room and bring a little cassette player and record what I’m doing, and try and write songs as well, just as a by-product of that. But to keep your sanity, I don’t know, it takes you about twenty years to find out. You know what all the ABC’s are to begin with, but there’s an awful lot of time to wear down the nerves of a musician. It’s just your attitude, really, in terms of traveling and flying, for hotels, for remembering where you are, and trying to keep all that group feeling every night to put on a good show. I mean, every musician has to go through that. You just have to develop a sense of humor and patience and just keep it cool, you know. I think the old cliché of deal with tonight’s gig and not worry about the one next Tuesday or the end of the tour or anything like that.

One day at a time.

Yeah. It’s a classic, but it’s true.

If someone was overhearing what you’re playing in the hotel room, would they be surprised? Are you a closet country player or a bluegrass guy or a flamenco player?

Flamenco, definitely. No, I do actually do some country licks. I’m quite keen on the playing of Roy Nichols, who used to be on Merle Haggard’s records, and some of the players that have worked with Waylon Jennings and Johnny Paycheck.

I’m surprised to hear that.

I don’t like this commercial country. I can’t really play flamenco that well – I can fake it, just for my own ears. I do a little bits of jazz things and ragtime – anything that will loosen you up. Also it’s good for your mental health not necessarily to do what you play onstage. And also even if you’re playing cassettes in your room. I play a lot of folk things, like Martin Carthy and some Irish music and some Django [Reinhardt] and things. Particularly if you’re doing a very long tour, it’s quite hard to listen to similar kind of music in your room then, I find. So it’s good to play something slightly different. And country and folk is quite a departure. That’s not to say I don’t play blues in the hotel room – I do. It depends what phase you’re going through, what year it is, and what mood you’re in and all those other things.

I am continually re-amazed at what a universal language the blues is.

Yeah.

How it speaks across borders to so many divergent people.

Particularly this recent interest in it. I was despondent in the late ’70s up until the mid ’80s – I thought we’d gone right into the age of technology, and that was the end of it. Drum machines, techno pop. So there’s this interest in the blues now in the early ’90s, thanks to Stevie Ray [Vaughan] and all the people who kept playing it, like Albert Collins and [George] Thorogood and all those people, to this peak that’s happening at the moment with this interest in Robert Johnson and John Lee Hooker and so on. And Bonnie Raitt’s comeback, if you like. Who would have predicted that? So that makes me very optimistic for the ’90s. I mean, if it gets better and better. Maybe it’ll fade away again, but I don’t think so. I think there’s going to be a nice, serious interest in the years to come, which would be great, you know?

Of course, a lot of people are interested in zydeco as well, and African music. And of course the whole world music thing is fresh for the ears, because people have had enough of mainstream pop lately. A lot of teenagers will surprise you. They say, “Oh, we love real drums. We love real bass guitars.” They get fed up with all that space-invaders machine music. That’s all it was, to my ears anyway. Because all that metronomic heartbeat stuff – I have a theory that’s bad for you. It’s like ticker tape, it’s like tele text. Because the heartbeat and the mind and everything doesn’t work digitally.

It’s more like reggae.

[Laughs.] Something like that, yeah. That’s a good way to put it, yeah. Somebody ought to check that out and see. It’s like some people have that theory about digital echoes – even though it’s in time, it’s different. You get tape echo that’s not entirely to the second. I don’t know – somebody had a ridiculous theory, but I kind of believe it.

I believe the time is coming when music will be used more to physically heal.

That it can do. Music can heal. It can cool down the savage breast, as they say. It does have that power. All kinds of power. By the time you subtract the music business and all of the good and bad things that go with it, you’re left with a piece of music and the player, and it’s important that that should remain fairly – not precious, but it should be left fairly organic and true.

What do you like to hear at the end of a show?

Our shows tend to become very rocky some nights – people jump around the place and all that. I can accept that, as long as they’ve listened to the slow blues and the acoustic and the blend. I like it to be fairly up at the end. You can’t pick and choose, but I don’t want it to be a recital where people politely clap. You have to create an atmosphere. But at any one show, I like, if I can, to hit about two or three different bases, in terms of reaction and performance. We try and create dynamics in the set, so it’s not just too predictable. “Oh, that’s going to be another number like that.”

You change the set around from night to night?

Oh, we do, yes. We rarely use a set list – only if it’s going to the airtime on a TV program, where they have to have cameras ready for whatever. We never use a set list. Occasionally, at, say, a big festival where your time is limited, it doesn’t hurt to have a list just to guide you a bit. But nine times out of ten, I just work off of the top of my head, and we move from album to album. Particularly on this tour, because we’ve been away so long, we’re not just only playing the new songs, we’re doing some old ones as well, just to refresh people’s memories.

You’ve been using the same musicians for a long time.

Yeah. The bass player since ’71 – Gerry McAvoy. Drummer since about 1980 – that’s Brendan O’Neil. The harmonica player for about six or seven years, Mark Feltham.

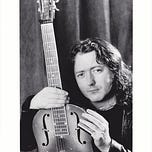

Not to make you self-conscious, but if someone were to put together a compact disc collection called “The Essential Rory Gallagher,” are there certain tracks you feel should be included?

I suppose so. If I were to do a best-of from the old days, things like “Cradle Rock,” “Million Miles Away,” “Tattoo’d Lady.” There’s lots of songs that I’d like to re-do and remix, things like “Race the Breeze” I was very fond of myself. I’d like to re-record that, and try to get a Staples Singers-type gospel feel to it.

Pops Staples is another underrated guitar player.

Indeed! Particularly on the early records, with that tremolo on that Jazzmaster, you know. To record a guitar like that, there’s so much room for it to breathe, you know. “Loan Shark Blues” is a song I like a lot – that’s to cite some track from the new one. It’s very hard for me to…. I mean, we’re going to do a box set or something like that later this year if not early next year, so that will be the real testing point of going back and seeing what’s there and what wasn’t released and things like that. That will be interesting.

What’s the scope of your current tour?

In America? We started in the West Coast. We worked around San Diego, two or three dates, and we played the Roxy in L.A. And then we’re playing in this area, Santa Cruz. We played Oakland last night, we’re playing San Francisco tomorrow night. We’re playing San Jose. And then we’re moving across to Minneanapolis – I can never pronounce that name!

Prince’s home town.

Yeah. We’ll do “Purple Rain” for him there. Actually, he plays good guitar, I think. He’s a very underrated player. And he’s clever to have that old Hofner Tele copy – they were good, and no one spotted them except one guitarist in Nashville who uses one. I think it was the guy who played on Dobie Gillis’ [i.e., Dobie Gray’s] “Drift Away.”

Was it Reggie Young?

I think it was Reggie Young. They have reissued these copies, but they’re not as good. But I must keep my eye out for one. We’re doing, obviously, New York, Boston, Detroit, Chicago. We’re going into Canada to do Toronto. We’re missing out on Washington, Dallas, and all the Southern area, but we’re hoping to come back in two or three months and cover that. We have commitments after Easter in Europe, so we have to go back. Ideally, we should stay here for two or three months, but given that we were in Australia and Japan before this – and this is a fairly hard month’s work – we’ll be glad to get back and get a week off.

Where’s your home?

Well, I’m based in London at the moment.

Do you get to Cork much?

Oh, I do. Because of the flying, I haven’t been there for a while, but if that’s over with, I’ll go back as I was for a while. I’d go back every third weekend or every second month or whatever. At one stage I was nearly commuting, which was great, because I like to keep my Irish connection. London’s a good town to work out of, but naturally it’s not home, you know what I mean? All the musicians live there and the studios and so on. But now since the Irish rock thing has boomed, it’s quite feasible to record and do things in Dublin. It’s become quite a rock and roll city.

Is that because of U2, etc.?

Well, U2 ultimately, yeah, but it was building up before they because of Thin Lizzy and Boomtown Rats and so on. The music industry took Irish musicians more seriously, whereas in the early days of Van Morrison and when we came out, it was quite hard to cut through the image. Everyone thought you were like the Clancy Brothers or just a dance band. There were very few serious rhythm and blues or rock people from Ireland at that stage. So it was hard to cut through, initially, but it’s great now. I’m half-tempted to record the next album in Dublin, just to see. I did three tracks on a Davy Spillane album – he’s a uilleann pipe player – and I enjoyed working in the Dublin studios. But for an Irishman, with the exception of the Irish Tour live album, I’ve never recorded in Ireland. It might be the X-factor, you know. Whatever that is.

Thank you! I really appreciate it. I am glad you could give us the interview.

It’s a pleasure.

###

Epilog

A few hours after our interview, Rory performed a long, stellar set at the Catalyst. He played many of the songs we’d talked about during the interview – his own “Continental Op,” “Tattoo’d Lady,” “Kid Gloves,” and “Million Miles Away,” as well as covers of Robert Nighthawk’s “Going Down to Eli’s,” Lead Belly’s “Out on the Western Plain,” Son House and Robert Johnson’s “Walkin’ Blues,” Blind Boy Fuller’s “Pistol Slapper Blues,” and Junior Wells’ “Messin’ with the Kid.” Dring the next two weeks, Rory and his band completed their final North American tour. Upon Rory’s return to the U.K., his health declined and his appearances became less frequent. Following complications from a liver transplant, Rory Gallagher, age 47, passed away at Kings College Hospital in London on June 14, 1995.

Credits: A special thanks to Rory’s brother and manager, Donal Gallagher, for making this interview happen. I also send my thanks to curator Steve Weiss and the staff of the University of North Carolina’s Southern Folklife Collection for digitizing my interviews. And a special shout-out goes to Nik Hunt for his help assembling this podcast.

For more details on Rory’s final years, visit the “Rewriting Rory” website created by Lauren Alex O’Hagan and Rain Morales: Rewriting Rory

Thank you for supporting independent music journalism!

© 2022 Jas Obrecht. All right reserved.

###

Share this post