Note to readers: This is part 1 of a three-part series.

By mid 1969, Jimi Hendrix was anxious for change. He’d spent nearly three years recording and touring as the Jimi Hendrix Experience, becoming one of the most famous Black musicians in the world. He wanted to take his music in a new direction, but record company and management pressure–especially from his personal manager, Michael Jeffrey–stood in his way.

On April 11, 1969, the Jimi Hendrix Experience began its final tour. For some of the shows, Experience bassist Noel Redding’s side band, Fat Mattress, served as the warm-up act. The relationship between Jimi and Noel had been tense for some time. As a result, on April 17 Jimi telephoned Billy Cox in Nashville and asked him to come to Memphis to meet with him after their concert the next night. After a long talk at the hotel, Jimi asked Billy to be on standby to join him as soon as the Experience tour ended.

It was natural that Hendrix turned to Billy Cox. They first met in 1961 at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, when they were both members of the U.S. Army’s elite 101st Airborne Division. After leaving the military, they had roomed together in Nashville and played in an R&B band, the King Casuals, during 1962 and ’63. They’d crossed trails a couple of times since then, such as when Jimi stopped by while on tour with Little Richard. Jimi had also reportedly invited Billy to fly to England with him just before the formation of the Experience, but Billy could not afford the ticket. At their meeting in Memphis, Billy recalled, “Jimi told me he was having trouble with Noel, so I agreed to join him.”

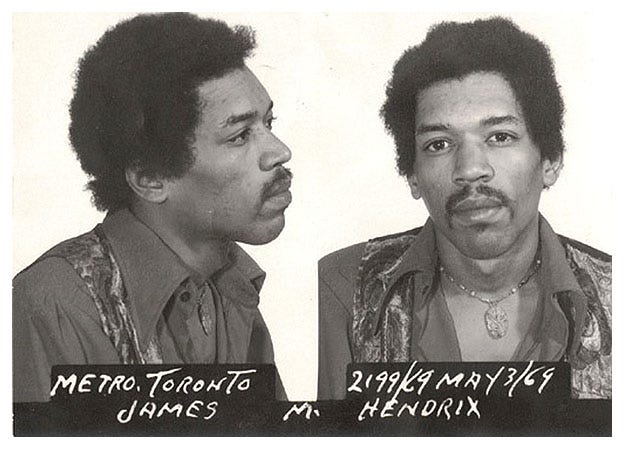

Life was about to get a lot more stressful for Jimi. On May 3, Jimi’s luggage was searched at Toronto International Airport, and he was arrested for heroin possession. It was widely rumored that Michael Jeffrey was responsible for planting the drug as a way of increasing Jimi’s dependency on him. For the next few months, the possibility of going to prison hung over Jimi. As the tour continued, Jimi took many opportunities to play with musicians outside of the Experience, appearing at various venues with Johnny Winter, Stephen Stills, Eric Burdon, drummer Buddy Miles, and Jefferson Airplane bassist Jack Cassidy.

On May 26, the Jimi Hendrix Experience and Fat Mattress flew to Hawaii for a series of concerts. After their final show on June 1, Noel Redding returned to England, while Jimi went to Hollywood, California, where he was joined by Billy Cox. Five days later, Jimi told interviewer Jerry Hopkins that Billy Cox would be playing bass for him in the future. Noel apparently was unaware of the upcoming change.

At a preliminary hearing in Toronto on June 19, Jimi was informed that his trial would begin on December 8, news that greatly upset him. The following day, the Jimi Hendrix Experience reunited for its final gigs–the Newport Pop Festival on June 20 and the Denver Pop Festival on June 29. Just before the Denver show, a reporter walked up to Noel Redding and said, “What are you doing here? I thought you had left this band.” Noel was visibly shaken by the news. During the show, rioting occurred between concert-goers and the police. Immediately after the performance, Redding fled to England. Thus ended the Jimi Hendrix Experience.

On July 10, 1969, Billy Cox made his first public appearance with Jimi, playing “Lover Man” on the Tonight Show. The next morning, the new issue of Rolling Stone contained the headline: Jimi Hendrix Has a Brand New Bass.” The article reported that “Hendrix has named an old Army buddy as the bass player he may soon be recording with and hinted that as soon as contracts allow, the Jimi Hendrix Experience may make the transition from trio to creative commune.” This “creative commune” would rapidly evolve into Gypsy Sun and Rainbows, the name Jimi choose for his Woodstock lineup.

Jimi explained: “It’s nothing personal against Noel, but we finished what we were doing with the Experience. Billy’s style of playing suits the new group better. See, Noel, he has his own group, and he’s into his own thing. I wanted the bottom to be just a little more solid. Noel’s more of a melodic player, and Billy plays more of a solid bass. We’re doing a lot of bass and guitar unison things, like a lot of rhythms and patterns.”

Years later, I asked Billy about his role in the new lineup: “Jimi tended to be a little more energetic with me than he was with Noel,” he replied. “Noel was a good bass player, but I guess Jimi felt more at home with me. It was a homecoming. He was more relaxed. My role was not to compete with Jimi, but to assist him an any way he chose. Of course, we had structure–we knew where we were going–but most of the time we just jammed. As long as it was feeling good, we’d go.”

The next step toward realizing Jimi’s vision of a bigger band was finding a second guitarist. Instead of bringing in one of his famous jamming friends, Jimi asked Billy to find Larry Lee, whom they’d known back in Nashville. In the excellent book Jimi Hendrix Sessions, co-written by Billy Cox, John McDermott, and Eddie Kramer, Billy explained: “Jimi had played both the rhythm and the lead with the Experience. He thought it might free him to concentrate on his lead playing if he had someone else playing rhythm. Larry Lee was the first and only guy considered, and Jimi gave me the assignment of finding him.

“In Nashville, Larry had been a sort of master to Jimi, teaching him some very important things he would need on this journey. Larry had taken Jimi by the hand and taught him a lot of things about the blues you couldn’t find in a book. That instruction helped Jimi put everything in perspective. Jimi respected Larry, and he knew that Larry knew as much about his own music as he did.” On July 14 Jimi Hendrix picked up Larry at a New York airport. The Woodstock lineup was nearly complete.

With the Woodstock performance just a month away, Michael Jeffrey rented an eight-bedroom mansion on Tavor Hollow Road in Shokan, a village about 12 miles from the festival site and about 100 miles from New York City. Jimi, Billy, and Larry moved into the mansion. Jimi invited a young percussionist, Jerry Velez, brother of singer Martha Velez, to move in with them. They were soon joined by a second percussionist, Juma Lewis, who was renowned around the Woodstock area for his work with the Aboriginal Music Society. “Jimi had broken up the Experience and wanted to do more ethnic music,” Velez reported in Jimi Hendrix Sessions. “He wanted to try African and Afro-Cuban music with a bigger band.”

On July 17, Jimi signed a contract to headline the Woodstock festival for $18,000; he would also be paid $12,000 for appearing in the film. While this fee was considerably less than what Hendrix was paid for festivals, it was higher than any other act at Woodstock. It was still unclear who’d be the drummer. The musicians rehearsed for several days without a drummer.

On July 30, Jimi suddenly disappeared. He told the others at the Shokan house he was going to New York City for the day, but wound up flying to Africa to spend six days tooling around Morocco, then a hippie haven, with some friends. The move infuriated Michael Jeffrey, who was nevertheless unable to stop Jimi. In Charles Cross’s essential book Room Full of Mirrors: A Biography of Jimi Hendrix, Deering Howe observed that this was “the best, and maybe the only, vacation Jimi ever had. Jimi had a ball. It was amazing to watch him, a Black man, experience Africa. He loved the culture and the people, and he laughed more than I’d ever seen him laugh.” During a two-day layover in Paris, Jimi reportedly hooked up with actress Brigitte Bardot.

On August 7, Jimi returned to upstate New York. He had just 11 days to prepare for what could be the most memorable gig of his life. Even at this late date, though, no one was fully aware of the magnitude of the Woodstock festival. When Jimi signed his Woodstock contract, only 60,000 tickets had been sold, and its promoters predicted its size would be less than 100,000. Rumors of a much larger attendance were already beginning to swirl around the Woodstock area.

At first Jimi worked with Juma on some acoustic guitar-conga arrangements. Juma described these as “phenomenal–a sound somewhat like Wes Montgomery or Segovia, but with a Moroccan influence.” Then they moved on to electric instruments. On Sunday, August 10, Jimi and his new bandmates made their first public appearance, jamming at the Tinker Street Cinema in Woodstock, where Juma often performed. This is believed to be the first time Jimi used a Uni-Vibe onstage.

Mitch Mitchell flew in from England, and on August 14, with their Woodstock performance just four days away, Jimi began rehearsals with the full lineup of Gypsy Suns and Rainbows. In his autobiography, Inside the Experience, Mitchell describes the scene at Shokan: “The band was grim and the house was grim. Jimi had installed Billy Cox and his lovely wife Brenda, and Larry Lee–a guitarist Jimi had known for years. He was another guy who hadn’t seen Jimi for ages and suddenly there is this whole other Hendrix to take in. Larry started putting a scarf around his head because he thought that’s what hippies did–looked very strange. A nice man and more than adequate guitar player, but did Hendrix need a rhythm guitarist?

“Also around were the two conga player, Jerry Velez and Juma Sultan, both good players in their own right, but there’s always a problem with two or more drummers or percussionists–either it works well or it gets competitive. It’s all right to have competition if you can count. If you can’t, you’re fucked. They couldn’t count. The band was a shambles. Apparently, they’d been working for about ten days when I got there, but you’d never have known. We were basically there because we were contracted to do the Woodstock festival, and I got the feeling several times during the rehearsals that Jimi realized it wasn’t working and just wanted to get the gig over and start again. It was probably the only band I’ve ever been involved with that simply did not improve over time.”

“There was a lot of percussion,” Velez agrees. “I was a novice, and both Juma and I overplayed. Mitch’s style involved a lot of playing as it was, with a lot of offbeat time signatures.”

Tape recorders were brought in to record the sessions. “Jimi knew I was a recording buff,” Billy Cox recalls. “At first we set up a Scully two-track machine, but it was just too difficult to operate and haul around. So we went to the office and got enough money to buy a Sony, which had sound-on-sound recording capabilities.” Among the songs that made it onto tape at the Shokan House and the Tinker Street Cinema are “Izabella,” “Beginnings/If 6 Was 9,” “Shokan Sunrise,” “Jimi’s March,” “Message of Love,” and various jams, including a flute instrumental. (Copies of these are easily found online, although their sound is often raggedy.)

According to Billy Cox, Lee’s choice of guitars, a semi-hollowbody Gibson ES-335, caused some friction. “I preached to Larry about getting a different guitar,” Cox explained, “but he preferred to play that 335, which was not musically compatible with where we were at musically. Consequently, it did not blend properly. I would tell him that he needed a Stratocaster, but he just didn’t listen.”

Part 2: Jimi Hendrix at Woodstock

Lots more Jimi Hendrix on Talking Guitar:

How Jimi Hendrix Learned to Play Guitar

The Jimi Hendrix Experience’s First Performances

When Jimi Hendrix Upstaged Eric Clapton

Jimi Hendrix’s “Purple Haze”: The Story of a Song

Jimi Hendrix’s “Red House”: The Story of a Song

Jimi Hendrix’s “The Wind Cries Mary”

The Jimi Hendrix Experience at Monterey

Jimi Hendrix: The Road to Woodstock

Jimi Hendrix’s Woodstock Setup

Roger Mayer on Making Effects Pedals for Hendrix, Beck & Page (Audio)

Joe Satriani: “When Jimi Hendrix Played the Blues”

Stevie Ray Vaughan: Our 1989 Interview About Jimi Hendrix

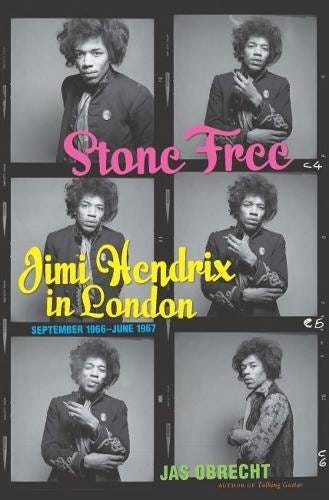

For an in-depth exploration of Jimi’s first nine months in London, check out my book Stone Free: Jimi Hendrix in London.

Help Needed! To help me continue producing guitar-intensive interviews, articles, and podcasts, please become a paid subscriber ($5 a month, $40 a year) or hit that donate button. Paid subscribers have complete access to all of the nearly 200 articles and podcasts posted in Talking Guitar. Thank you for your much-appreciated support!

©2024 Jas Obrecht. All right reserved.

I saw Jimi 4 times, carried his guitar into a jam sessionwith the Butterfield band at the aragon here in Chicago. I think he lost a lot after those first 3 albums. Not a fan of Band Of Gypsies. Buddy Miles wasn't the answer. Phillip Wilson of the Butterfield Band had it all...easily the best drummer Jimi ever played with. My opinion. I've been playing lead guitar for 50+ years. I've played with Buddy Miles at a Hendrix Birthday Party jam at Buddy Guy's Legends...just saying.