Cover Story Stories 2 takes up where Cover Story Stories 1 left off. These write-ups are presented in chronological order. Click on the underlined passages to view transcriptions of the interviews and/or hear the original audio. Hope you enjoy these memories!

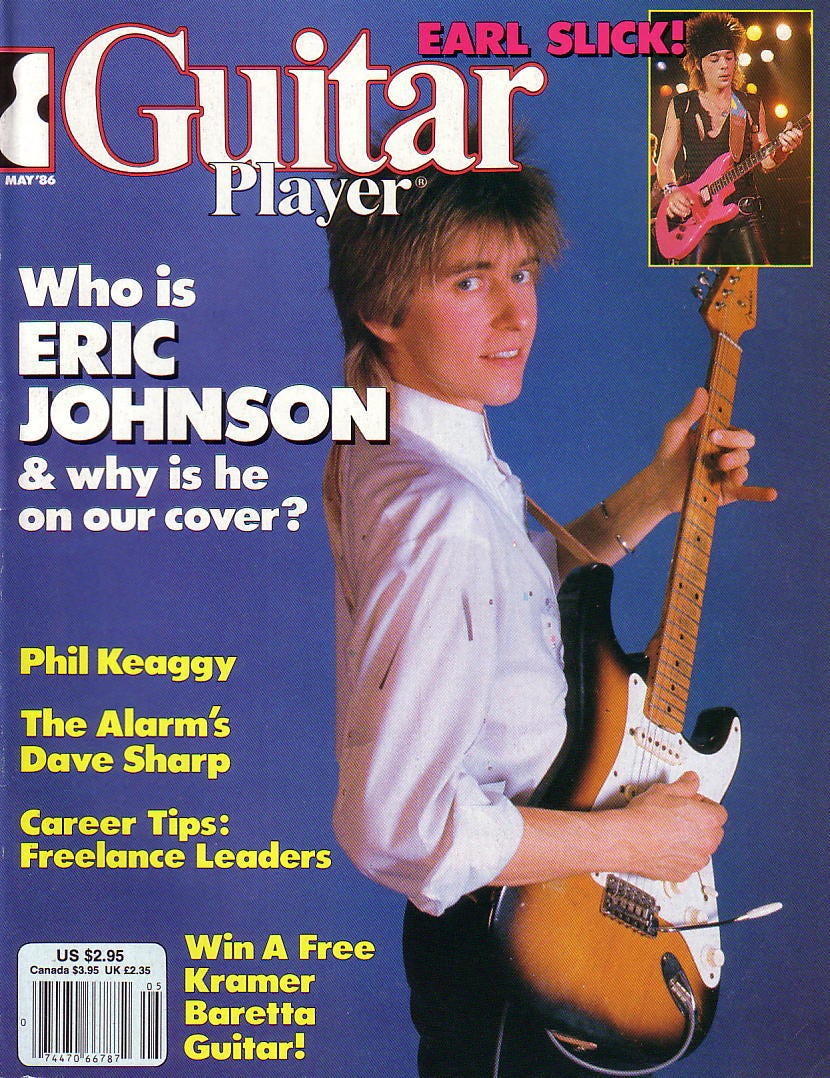

Guitar Player broke a longstanding precedent with the May 1986 Eric Johnson cover story. Until then, a hard-and-fast rule held that players couldn’t be considered for covers unless a reader could go to a record store and purchase their albums. When we decided to put Eric on the cover, his recording credits consisted of guest appearances on LPs by Carol King, Christopher Cross, and Steve Morse; the out-of-print Electromagnets album and Mariani’s hard-to-find Perpetuum Mobile; and a spectacular 1984 televised performance on Austin City Limits.

In late 1985, Eric’s manager Joe Priesnitz sent me an advanced cassette of Eric’s Tones album, which Reprise Records had scheduled for a June release. When Tom Wheeler and I heard it, we were stunned. As I wrote in the intro to Eric’s debut cover story, “His playing blends deep emotion with wide-ranging technical finesse. He often highlights intriguing chord voicings, and his solos are consistently brilliant and packed with feeling. The album’s collage of guitar tones range from purest-of-pure Strat to Hendrix psychedelia to majestic, violin-like textures.” We talked our publisher, Jim Crockett, into featuring Eric on the cover before his debut solo album hit the record racks.

Eric and I had done a 90-minute phone interview four years earlier, based on the strength of an unreleased demo tape he’d sent me called Seven Worlds. At the time, he was basically laboring in obscurity in his hometown of Austin, Texas (read it here: Eric Johnson: Our Complete 1982 Interview). We met in person for the first time in late January 1986, when we spent two days together doing the cover interview and photo shoot. (Here’s the audio: Eric Johnson: The Complete 1986 “Tones” Interview.)

I was happy to learn that beyond being a fabulous musician, Eric’s an extraordinarily earnest, thoughtful, humble, and nice human being. Through his bandmates I also heard that he has perfect pitch. One example cited by drummer Tommy Taylor: As the band was leaving the studio one day to take a lunch break, a garbage man tossed an empty trash can back onto the street. As he heard it bounce on the ground, Eric called out “C#.”

We met with Mary Beth Greenwood for the photo shoot. While Mary Beth finished setting up her equipment, Eric was noodling around on his plugged-in Stratocaster. We’d been talking about Jimi Hendrix, and I casually said, “I wonder how Jimi would have played ‘Amazing Grace.’” Eric immediately launched into that famous old song, sounding just like Jimi Hendrix might have if he’d channeled the gentle approach heard on “Little Wing.” As Eric finished, I said, “How about Wes Montgomery?” Same thing—Eric’s thumbed octaves sent shivers up my spine.

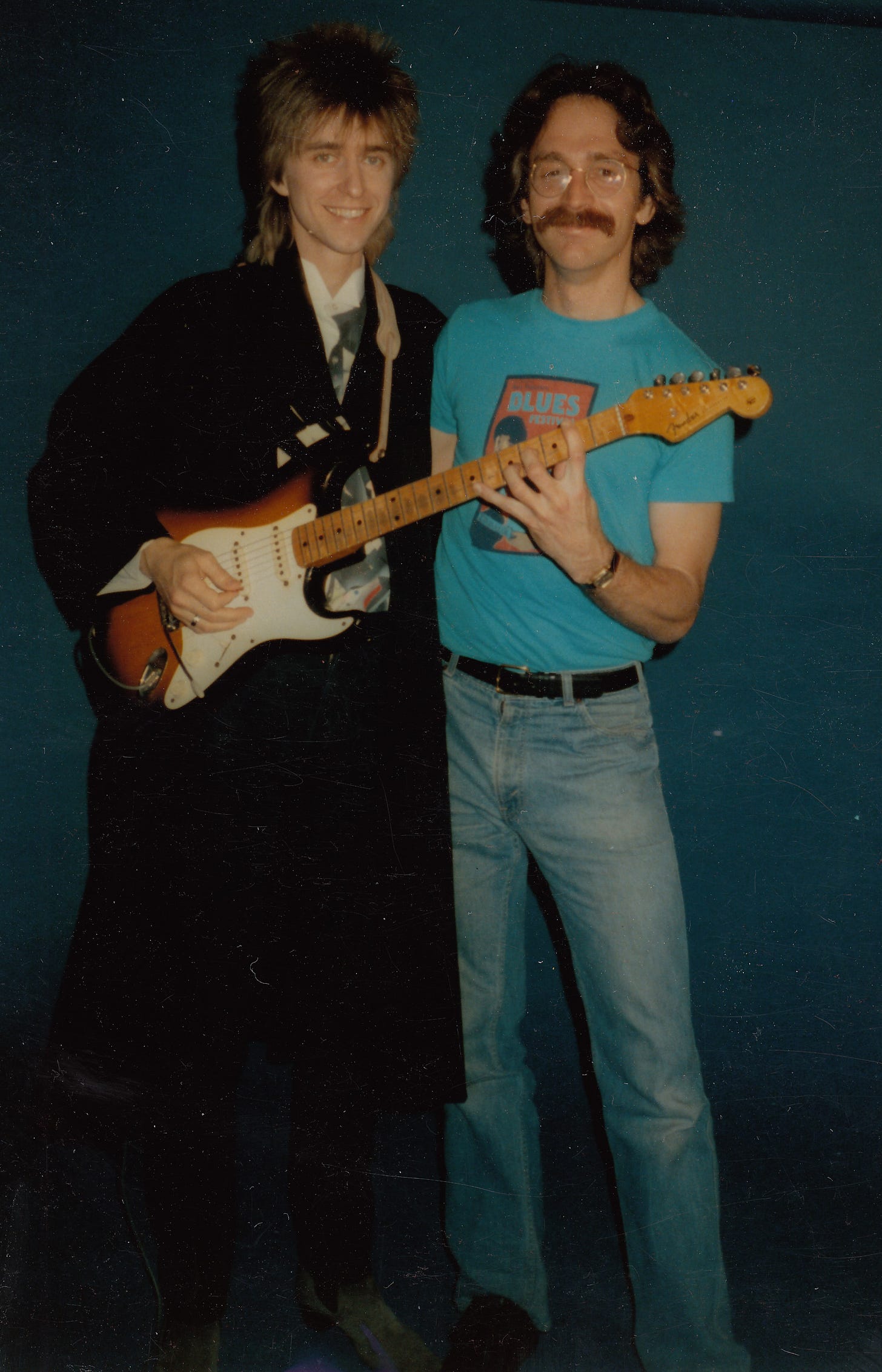

I’d brought along my little Nikon sure-shot camera, and Joe or Mary Beth snapped a few casual shots of us. This one captures our vibe that day:

I’d like to take ownership for the cover type—“Who is Eric Johnson & why is he on our cover”—but that credit goes to my friend Tom Wheeler. And it was Tom who handled the negotiations with Austin City Limits that enabled us to release Eric’s “Cliffs of Dover” as the issue’s tear-out vinyl Soundpage.

As soon as the May 1986 issue came out, Reprise Records reproduced the cover and interior pages in press kits distributed to radio stations, publications, journalists, and record stores. For Eric and me, that issue was the start of an enduring friendship.

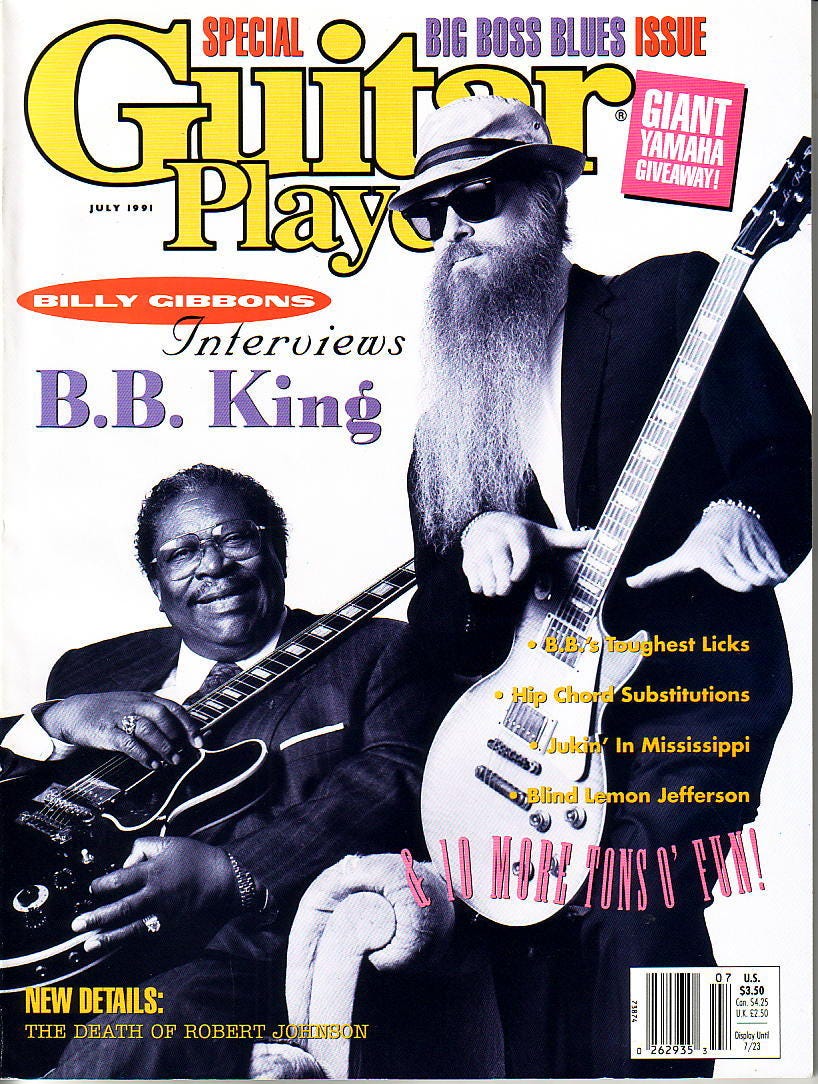

Billy Gibbons and I have long shared a love for postwar blues. During the 1980s we did two cover stories together and often communicated with each. Billy would occasionally mail me cassette tapes he’d made of vintage blues records. These tracks typically featured hair-raising electric guitar from the late 1940s and ’50s. One of us—I forget who—remarked that it would be cool to get together to interview one of our mutual heroes, B.B. King, about his early days in Memphis.

Luckily, B.B. loved Guitar Player magazine. While in the San Francisco Bay Area he’d stop by to visit with Jim Crockett and our staff. He’d even sat in on one of our company’s monthly jam sessions. When asked about doing a joint interview with Billy and me, he quickly agreed. After weeks of negotiations with managers, we found a time when Billy had a few days off from ZZ Top. Our office manager, Lonni Gauss, made the arrangements for the interview to take place when B.B.’s tour took him to Indianapolis.

Billy and I met at the airport. As we waited at the luggage carousel, a cheap guitar case with a bungee cord wrapped around it came up the conveyor. Billy grabbed that case and the rest of his luggage, and off we went in a limousine.

The interview took place the next morning in my room at the Embassy Suites. B.B., gracious and accommodating throughout, showed up in a suit. To set the mood, I’d brought along a sepia-toned video of Bukka White, with whom B.B. had roomed in Memphis around the time he made his first records. A minute or so into the interview, Billy said, “Let’s show that little piece of film we peeked at, which shows someone you know playing lap-style.”

As the video began, B.B.’s eyes widened. “Bukka White!” he exclaimed. “That’s my cousin.” He laughed heartily and added, “Thank you! Old traditional blues song. I sure appreciate this. You don’t know what you’re doin’ to me.” We were off and running.

That evening Billy and I went out for dinner before taking in B.B.’s performance. As if his beard wasn’t recognizable enough, atop Billy’s head was a baseball cap emblazoned with a ZZ Top logo.

Midway through our meal, a woman about a decade older than us approached the table. “Mr. Gibbons,” she said, “I’d like to ask you a question.” Billy told her to go ahead. She said, “Over or under?” Billy shot me a quizzical look. Again, the woman asked, “Over or under?” “I’m sorry, ma’am,” Billy politely responded, “I don’t understand.” She replied, “Do you sleep with your beard over or under the covers?” “Ma’am,” Billy smiled, “that’s a story that’s never been told.” As she walked away, I asked him if he was often asked this sort of question. “More than you’d imagine,” he replied, dousing his food with hot sauce from the bottle he carried in his sportscoat pocket.

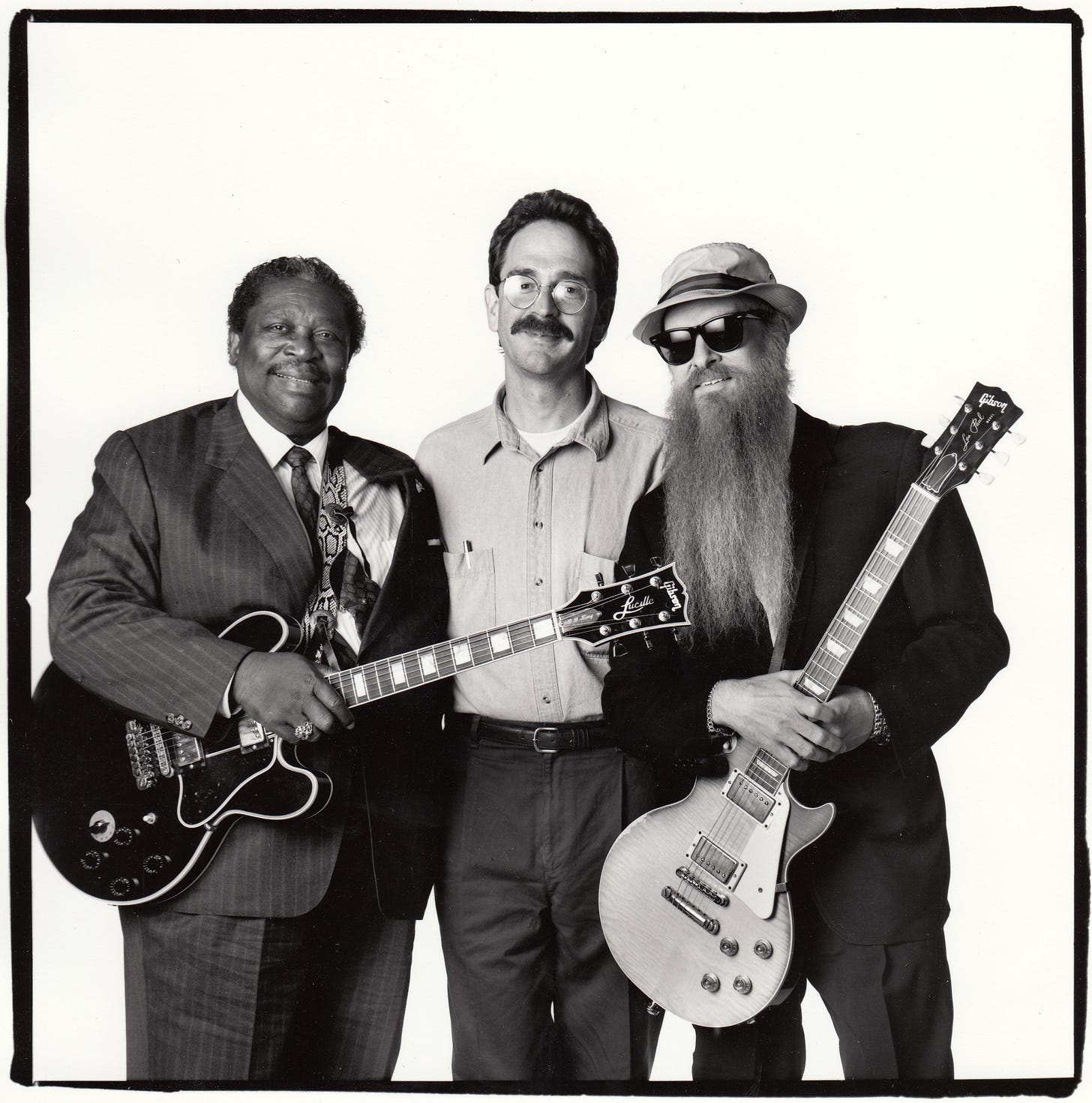

The next day we met at a rented studio with the always-excellent Bill Reitzel for the cover photo shoot. As Bill set up his camera, Billy unfastened the bungee cord, opened up his guitar case, and pulled out his most famous guitar, Pearly Gates. I was stunned. “Gibbons,” I exclaimed, “I can’t believe you put a ’59 Les Paul in airline luggage. Why didn’t you buy it a seat?!”

Billy smiled slyly and handed me the guitar. “Take a real close look at it, amigo.” Holding it inches from my face, I saw that someone had glued a full-sized photograph of Pearly Gates’s distinctively flamed maple top onto the face of another Les Paul and varnished it over. From more than a few inches away, you’d swear that instrument was Pearly. “American ingenuity,” Gibbons said, sagely raising his index finger, “does not end with the paint job.” A good time was had by all.

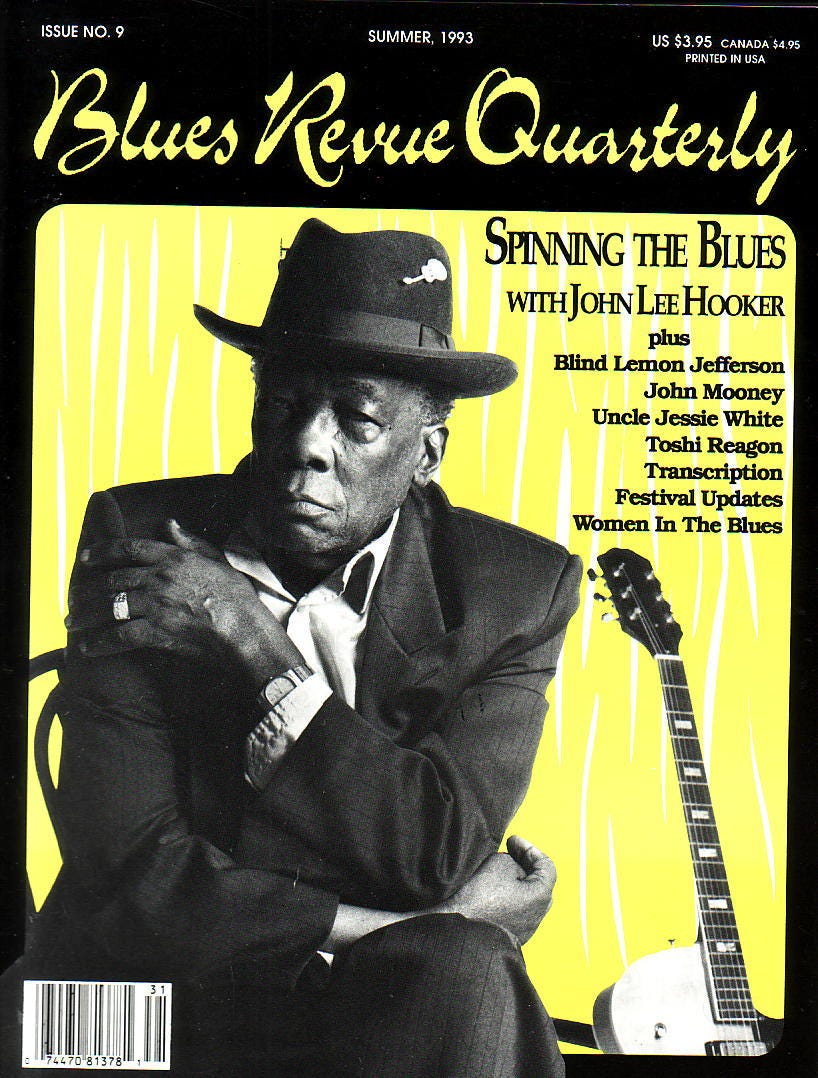

Since my early teens, I’ve felt a real affinity for John Lee Hooker and his music. Seeing him perform solo when I was an incoming freshman at Detroit’s all-boys Jesuit high school sparked my love for blues music. His 1966 Live at the Café Au Go-Go, recorded about a month before he played my high school, was the first blues album in my collection.

When we began doing interviews together—first for Guitar Player, and then Living Blues, Blues Revue, and Mojo—John and I discovered that we had a few things in common. We’d both spent decades living in Detroit before moving to California. We’d both pushed brooms in the steel-rolling mill of the Ford Rouge plant. To top it off, a girlfriend I’d lived with in the early 1980s moved into his house right after we broke up. John sometimes had trouble remembering who people were, especially later in life, but every time he saw me he’d say, “You’s Bonnie’s guy!” and flash me a knowing smile.

My favorite cover story interviews with him are John Lee Hooker: The Complete 1996 “Living Blues” Interview and B.B. King and John Lee Hooker: Their Only Interview Together. Another memorable one, for Blues Revue Quarterly’s Summer 1993 issue, took place in his spacious home in Redwood City, California, on December 29, 1992. Rather than retread old ground, we decided to have a listening party. So I brought along a stack of blues records that I figured he’d enjoy talking about.

John offered insightful comments as I spun T-Bone Walker’s “Trinity River Blues,” Albert King’s “Personal Manager Blues,” B.B. King’s “Miss Martha Blues,” Lonnie Johnson’s “No Troubles Now,” Memphis Minnie’s “Ma Rainey,” Lucille Bogan’s ultra-salacious “Shave ’Em Dry,” Robert Johnson’s “Preaching Blues,” and his own early 78s “Shake Your Boogie” and “Good Business.”

I got the impression that his favorite song that evening was Blind Blake’s “Hastings Street,” which he hadn’t heard before. Blake’s lyrical references to 169 Brady and Hastings Street in Detroit resonated with John, who knew exactly where these locations once were. “Brady was right off of Gratiot,” he explained. “Brady Street is gone now; I don’t think it is no more. Hastings Street is gone. Jefferson is still there, Gratiot is still there.

“When I got to Detroit, Hastings Street was the best street in town. Everything you wanted was right there. Everything you didn’t want was right there. It ain’t no more. It’s a freeway now, called Chrysler Freeway. But that was a good street, a street known all over the world.” About Blake’s playing, he said, “That’s the old sound there. That’s the real blues.” (A transcription of this interview appears in my book Rollin’ and Tumblin’: The Postwar Blues Guitarists.)

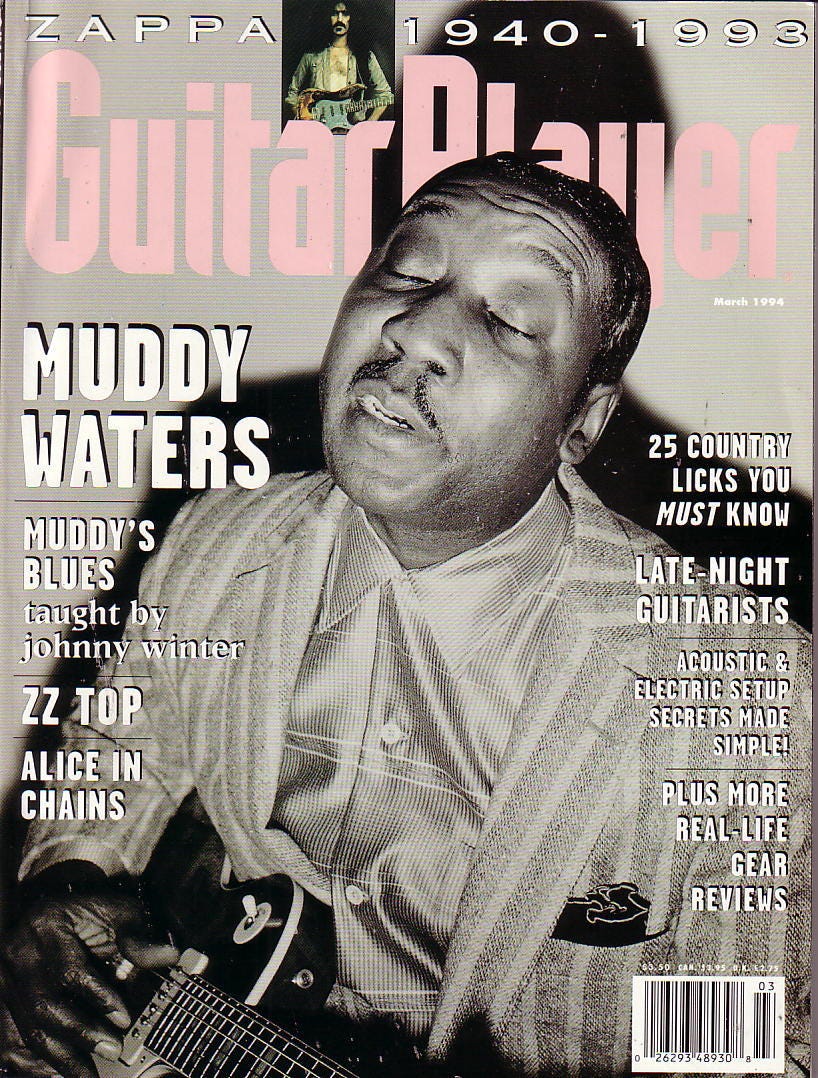

I never did a formal interview with Muddy Waters—that honor went to Tom Wheeler, who wrote the Guitar Player cover story published a dozen years before the 1994 issue depicted here. But I was blessed to spend some time with him backstage when he played two nights at California’s Paul Masson Winery in September 1981.

Muddy carried himself with great dignity as he moved about backstage. He was relaxed and self-assured. He smiled as he entertained us with his account of growing peppers that summer that were so hot they’d burn any fingertips that touched them. Before going onstage, he left us with that unusual handshake of his seen in the famous 1950s photo where he’s gripping another musician’s fingertips rather than doing a full-press palm-to-palm. His performance that night was electrifying. A lion in winter.

As the 1980s progressed I carefully kept up with popular releases and changing musical styles. I read the music trade magazines and scanned the record charts in every issue of Billboard. As more and more styles emerged, this grew tiresome. When Guitar Player hired younger editors such as Joe Gore and James Rotondi, I was able to turn over a significant portion of this “keeping up with the trends” to them, and they rose to the occasion. As did Andy Ellis, Art Thompson, Chris Gill, and a few trusted freelancers.

This freed me up to devote more time to writing about the historic music I care about most. My March 1994 cover story about Muddy Waters is a good example. Headlined “The Life and Times of the Hoochie Coochie Man,” the article covers his influences, recordings, and the history of his life from his birth in rural Mississippi to his death in 1983. It’s among the longest and most in-depth articles published in Guitar Player.

While writing it, I spent nearly two weeks surrounded by albums, books about the blues, transcripts of old interviews, back issues of Living Blues and other magazines, and the most recent editions of the essential reference books Blues and Gospel Records 1902-1943 and Blues Records 1943 to 1970.

In the process, I fine-tuned the researching and writing techniques that would come into play as I wrote 2015’s Early Blues: The First Stars of Blues Guitar and 2018’s Stone Free: Jimi Hendrix in London. I still use them today for my “Let It Roll: The Essential Blues Recordings” feature articles, which have appeared in every issue of Living Blues for the past five years.

The best perks of the Muddy Waters cover: I got paid to immerse myself in the music of one of the greatest bluesmen to make it onto record, and I came away with a deeper understanding of the man whose music changed Chicago blues.

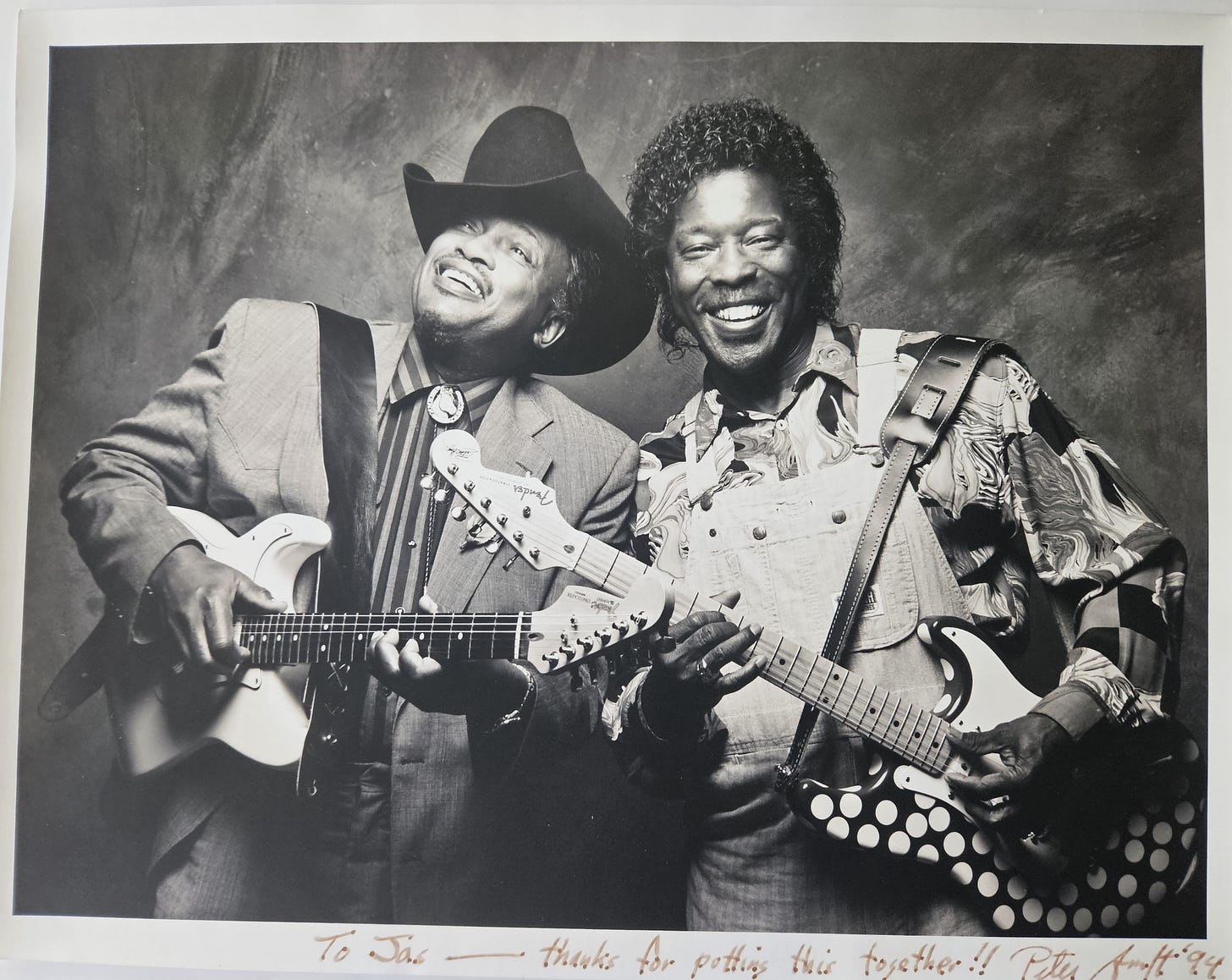

As any postwar blues aficionado can attest, Buddy Guy, Otis Rush, and Magic Sam played essential roles in the rise of the edgy, amplified “West Side sound” of Chicago blues during the late 1950s. All three recorded breakthrough singles for Cobra Records. Otis was the first to find fame, with his 1956 hit “I Can’t Quit You Baby.” Magic Sam was the next to land a record in the charts, with his tremolo-drenched “All Your Love” in 1957. With Otis Rush on second guitar, Buddy made his first Chicago-based recordings in 1958. (For more details on this period, see my post “Otis Rush at Cobra Records.”)

Magic Sam did not survive the 1960s, while Buddy and Otis were still hitting it hard in the mid-1990s. By then I’d interviewed each of them separately, doing a Guitar Player cover story with Buddy for the April 1990 issue and interviewing Otis for Guitar Player’s November 1993 cover story. I felt an affinity for both men.

Discovering that they had never done an interview together, I contacted Buddy’s manager and Otis’s wife Masaki and asked if we could get them together to talk about the old days. Arrangements were made.

Buddy and I rendezvoused at his Chicago nightclub, Legends, around noon on June 8, 1994. Buddy, as gracious a host as you could encounter, was effusive and effervescent as we waited 45 minutes for Otis’s arrival. He broke into a big grin when he saw Otis come through the door. They greeted each other with a handshake and a hug. “Sorry I’m late,” Otis said. “Oh, don’t worry about that!” Buddy responded. “This guy can be late any time! C’mon, make yourself at home.” “Okay,” Otis replied. “Let me run the bar if that’s the case.” They both laughed, and Otis poured himself some white wine on the rocks.

For the next hour and a half the old friends recollected their salad days in Chicago, celebrated career highlights, and commiserated on the downturns. Naturally, the subjects of Muddy Waters, Willie Dixon, Magic Sam, Earl Hooker, Leonard Chess, and others on the Chicago scene came up. For me, the most fascinating parts came when the discussion turned to how to write songs, create guitar riffs, and the pros and cons of mixing drinking and performing.

We’d hired Peter Amft to photograph Buddy and Otis for the cover that same afternoon. Buddy always played right-handed. Otis, a southpaw, held his guitar the opposite way and strung it in reverse, with his low-E string closest to his toes. At one point during the shoot, the two friends decided to mimic the way the other held his instrument. After the interview came out, Peter sent me this inscribed photo, which has hung on the wall of my writing room ever since:

At the tail end of our time together, Otis revealed to Buddy that he’d given elaborate names to all three of his guitars. “Yes, sir,” he said. “One of them is ‘Check Me Out And If I’m Wrong I Don’t Want To Be Right.’ I also got ‘C’mon Smooth And Let Me Live.’ What lets you live? A pretty guitar hangin’ on your shoulder. What lets you live? Your guitar lets you live! Huh? It bring you the money, man. If you don’t have it, they might not pay you. My other guitar is ‘I’m Gonna Take ’Em To Meet Lucy And Lucille And See If We Can Make a Deal.’” We all laughed.

“Guitars bring a lot of joy, man,” added Buddy.

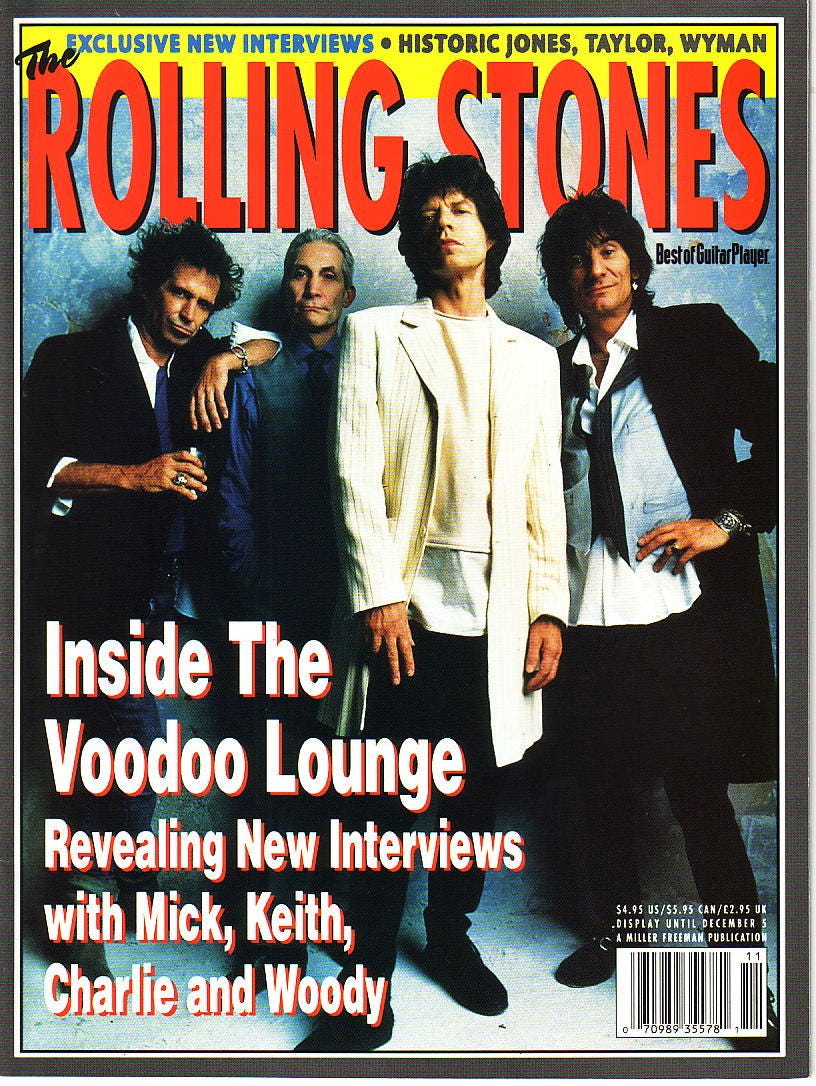

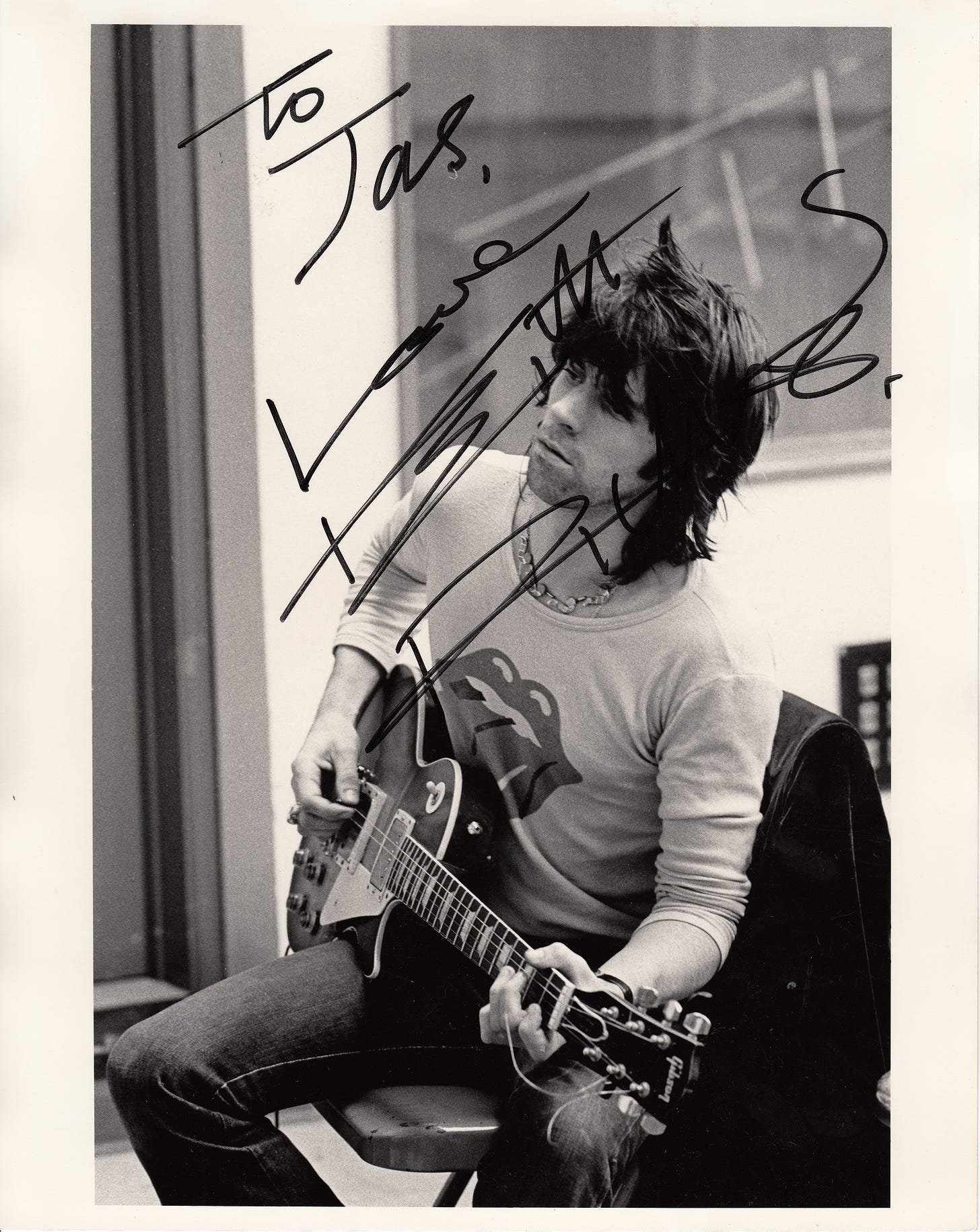

My first cover story interview with Keith Richards—Guitar Player, December 1992—took place in the Manhattan office of his manager, Jane Rose. I knew Keith was an avid fan of Robert Johnson, so I’d brought along hard-to-find Library of Congress recordings that Calvin Frazier, who knew and sounded like Johnson, had made in Detroit in 1938. Keith, who’d never heard them, was gobsmacked by the similarities. I played him a couple of other rare blues, much to his delight: “This ain’t an interview, man, it’s a party!” We hit it off.

Fast forward three years. The Rolling Stones announced that they were going on tour in support of their Voodoo Lounge album. I’d already written and edited about a dozen “one-shot” magazines, and I saw potential in doing a Rolling Stones one to sell at record stores, newsstands, and wherever they performed. I contacted Jane Rose, who, in turn, asked Keith what he thought. “Let’s do it!” he responded.

With Keith’s blessing, it was arranged that I’d fly to Toronto and interview every member of the band. In order to have the 82-page magazine written, edited, printed, and shipped in time for the tour, I had exactly 11 days to provide all the words. The pressure was on.

The day before my flight, I was watching a TV show with Michelle, my wife of three months. An ad showing a baby came on, and she uttered a heartfelt “Awww.” This was unlike her. I quipped, “What’s up with that? Are you pregnant or something?” We bought a test strip and, sure enough, she was pregnant with our first and only child. Suffice to say, I felt a whirl of emotions as I boarded a jet early the next morning.

Arriving in Toronto on July 14, 1994, I booked into the same hotel as the Stones. The band’s rehearsals were being held at Crescent School, a private high school they’d rented for a few weeks. I rode there in a van with Charlie Watts, Bobby Keys, and two of the backup singers. When I saw Keith, he greeted me warmly and asked, “How ya doin’, man?” I told him that I’d just found out yesterday that my wife was pregnant. “Don’t name the baby after me,” Keith advised, “especially if it’s a girl!”

My interviews with Mick Jagger, Charlie Watts, Ronnie Wood, keyboardist Chuck Leavell, and bassist Darryl Jones took place across a barren table in the school’s empty cafeteria. My conversation with Keith came down in Room 311, a classroom that he had redecorated in a harem motif with newly installed deep red tapestries, plush carpeting, instruments, a low-slung table, and a comfortable couch and chair.

In one part of the interview, I mentioned to Keith that sometimes I hear a real Bakersfield influence in Mick’s country twang. “Yeah!” he responded. “It’s funny, I don’t know why. It’s not Nashville. You’re right—it’s Bakersfield. I know he listens to—and used to—a lot of Merle Haggard.”

Keith invited me to attend that evening’s hours-long rehearsal in the school’s gymnasium. When they’d finished running through “Far Away Eyes,” Richards looked over at Darryl Jones and yelled “Shit, that’s country!” Then he turned, pointed to me, and wheezed “Bakersfield!” through his lit cigarette. He accompanied his observation with a half bow and palms-up, outstretched arms.

I flew home the next morning. Using my 1979 interview with former Rolling Stones guitarist Mick Taylor to fill the remaining pages, I made the deadline.

Something Mick Jagger said to me in Toronto proved prescient. When I told him of my wife’s pregnancy, he advised, “Watch out for the ninth month. It goes on forever!” Sure enough, my daughter Ava was two weeks late, waiting until the first day of spring to greet the world.

###

Thanks to Nik Hunt for helping with the graphics.

To help me continue producing articles such as this and podcasts of guitar-intensive interviews, please become a paid subscriber ($5 a month, $40 a year) or hit that donate button. Paid subscribers have complete access to all of the 150+ articles and podcasts posted in Talking Guitar. Thank you for your support!

©2024 Jas Obrecht. All rights reserved.