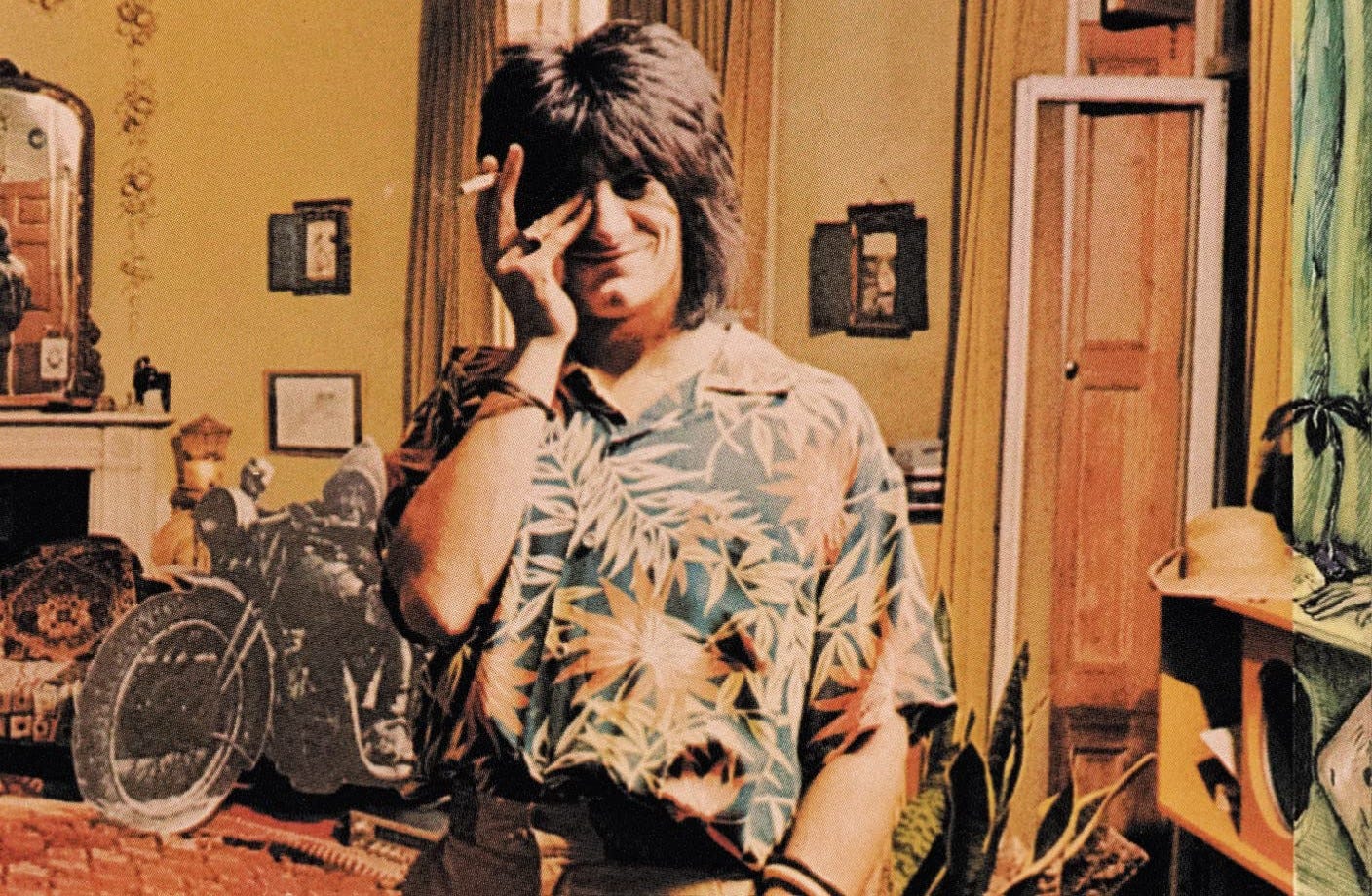

Ronnie Wood: On The Jeff Beck Group, Faces, Rolling Stones, and Slide Guitar

Our Complete 1994 Interview

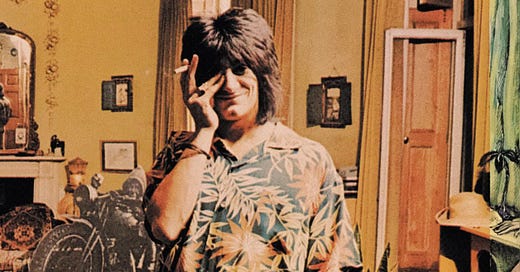

Ronnie Wood first found fame as bassist in the original lineup of the Jeff Beck Group. Then in the early 1970s he distinguished himself as the lead, slide, and pedal steel guitarist for The Faces and Rod Stewart, with whom he played on The Rod Stewart Album, Every Picture Tells a Story, and other classic LPs. In 1974, he replaced Mick Taylor in the Rolling Stones, a gig he still holds today.

Wood’s amplified lead guitar sound is one of the most distinctive in all of British rock and roll – sure-handed, heartfelt, and scrappy, all at the same time. Deeply rooted in prewar American country blues and postwar Chicago blues, his acoustic and electric guitar slide playing likewise have great depth of character and an appealing, bittersweet sound.

Our interview took place on July 14, 1994, in the empty cafeteria of Toronto’s Crescent School, where the Rolling Stones were rehearsing for their Voodoo Lounge tour. The previous evening, I’d been invited by Keith Richards to watch the band rehearse in the school’s gymnasium, an event Ronnie references in our interview. On the table in front of us was a photograph of various guitar slides that guitarists used over the past century. Ronnie examined the photo and pointed excitedly to an old hunk of thin copper pipe. This jumpstarted our conversation.

****

Copper pipe – that’s what I use! 3/4”. I also use the Stevens bar with the lap steel and a Bullet bar with the pedal steel, and I’ve used knives and lighters.

You have a very distinctive slide tone. The second you hear it, you know it’s Ron Wood.

Right.

It’s on some your Rod Stewart records, the Stones’ “Sweethearts Together.”

That’s the lap steel. It’s an old one I got for $150 from an old lady’s attic. Apart from the distinctive pedal steel sound, which you can only get by them pedals, I’ve always used the black Zemaitis 6-string for slide, the “Stay with Me” guitar. I use the B-bender and the lap and the black Zemaitis in open tuning. I play slide on normally tuned guitars as well.

Where did your interest in slide begin?

Duane Allman. When I heard him play on [1969’s] “The Weight” by Aretha Franklin. I was playing bass with the Jeff Beck Group, and when that folded I immediately went into slide. Picked it right up. I’d never really played it before.

Did anyone help you?

No. I just did it. I learned that very quickly, and the harmonica as well – blow and bend like Jimmy Reed.

Did your initiation into slide lead you on a journey back to older players?

Oh, yeah. But I’d already been hip to old slide players – Blind Willie McTell on the 12-string and those kinds of players. Leo Kottke was a modern-day kind of player. Remember that album with the armadillo? [Takoma’s 6- And 12-String Guitar.] Boy, that was really a door opener. Yes! There’s another guitar player called Hop Wilson. I got songs that I wrote like “Black Limousine” from him, those kind of licks. I thought Mick Taylor was a really good slide player. I liked him on things like “All Down the Line” and “Love in Vain,” you know.

Slide lets you hit the notes between the notes.

Yeah! And a lot of it is by accident. You hear a lot of great things. People say, “Oh, how do you do that?” When I first went into slide, I only learned [sings Duane Allman’s opening figure from “The Weight”], like Duane did on “The Weight,” and then I took it from there. I tuned my guitar to open E, and that’s when I got my first slide instrumentals, like [the Small Faces’] “Plynth.” And then I carried on that tradition on things like “That’s All You Need” and “Borstal Boys” with the Faces.

Yeah. That was pedal steel. First time I played pedal steel, as well. I picked it up [snaps fingers] just like that.

So not long after hearing it, you were playing slide on records.

Probably the same day. As soon as I could get the instrument, I’d play it. I’ve always been lucky like that – very quick to pick up.

Do you follow Elmore James’ technique that it’s better to record slide at a low volume?

Now I would. Now I’ve matured a bit. But in the early days it was 11! [Laughs.] Actually, when I did things like “Plynth” in the studio, they weren’t very loud, yeah. You get a much cleaner sound. But funny enough, the Elmore James sound to me sounds like the amp’s on overdrive, sort of like it’s in distortion mode.

Homesick James, who played bass on those records, insists that Elmore would not play loud in the studio.

Eric [Clapton] probably picked up a lot of that approach, because he likes to play it soft as well.

You had a lot of opportunity to express yourself on Voodoo Lounge.

Yeah.

Are you happy with it?

Yeah! The Edge’s guitar man, Dallas Schoo, gave my roadie Church a big compliment yesterday. He rang up and said, “Oh, man, who’s playing that steel on the album? Did you get someone in from Nashville?”

Or Bakersfield.

Yeah! Didn’t sound like Nashville to me, but he thought they brought a pro in, you know, who just does that.

How did that happen to get on there?

[Producer] Don Was is very encouraging. He’d suggest, “Hey, how about a pedal on this one? How about a lap?” I would be thinkin’ it, but I thought, “No, it wouldn’t get used.” Don would say it once, and everyone goes along with it. He’s so easy to work with.

What are your favorite tunings for pedal steel?

Well, as I call it, the Nashville tuning. There’s a Hawaiian one, isn’t there? There’s one that’s C6 – I think that’s Hawaiian – and I use the other one. E9? Whatever that means! But, you know, with the ten strings you go [sings an E9 tuning from high to low]. That’s all I know!

Since it doesn’t have frets, does the steel guitar seem like more of an unlimited instrument?

No, because if you hit one of the ten strings that is not fitting in that particular chord, you can do an enormous blunder. There’s only certain strings you can hit to make a thick chord. I have to be very careful on that song “The Worst” [sings solo] – that last note there is going into restricted area. If you hit another one right beside it, it goes blech!

What’s your all-time favorite slide setup?

You should have Church up here, because he could give you some inner details only he knows. I just plug in. “Am I ready? Let’s go!” [Laughs.] That’s my approach. I don’t get into the technics of it too much. For 6-string slide my favorite setup in the open-string tuning would be the Zemaitis, or in the old days a Dan Armstrong – they were great. The Plexiglas. I made the mistake of giving that to David Bowie. I thought I could get another one, and I couldn’t. Also in the open-string mode, I love my Fender lap steel. Going through a Fender Twin or Mesa Boogie, even if it’s my regular-strung guitar, like my Les Paul Special that Jesse Ed Davis gave me. He used to play that with Taj Mahal; it’s a very special sound. I also use an Ampeg and a Vox AC30, and maybe incorporate a little Fender amp in there.

It’s interesting to hear you sing parts. Is that your approach when you hear a song for the first time?

Yeah. I’ve always done things by ear, whether it’s playing a guitar, a saxophone, piano, or harmonica.

Are you a schooled musician?

Yeah! I got lots of lessons in the art class and in the choir. I went from treble to alto to tenor to bass in the choir, all through my school years. It was Church of England, singing in cathedrals – St. Paul’s, Coventry – on behalf of the school, and it was great. I also had a jazz band at school as well. We used to get special permission to rehearse and play every now and again. We used to do Dave Brubeck stuff.

Did you share Mick and Keith’s love of blues?

Yeah, because my older brother Art, who’s ten years older than me, had the Artworks with Jon Lord and Keef Hartley. Art started with Cyril Davies and Alexis Korner, who were the blues pioneers in England. So while I was in short pants, I used to go down and see Cyril. I saw musicians like Nicky Hopkins, Colin Little, the drummer, who used to get me a lot of imports of Chuck Berry – “Blue Feeling,” that’s another lap steel piece that was a big turn-on for me – and “Deep Feeling.” Those records are marvelous. My other brother Ted, who’s eight years older than me, was in a traditional jazz band, playing Johnny Dodds, Louis Armstrong, and Bix Beiderbecke. They had a band that used to be allowed by my parents to rehearse in the back room, so while I was little there were always instruments knocking around. There were woodblocks, saxophones, clarinets, guitars, banjos, comb-and-paper, kazoos.

So your brothers were coming out of skiffle.

Yeah. I made my first appearance playing washboard at nine years old, between two Tommy Steele films at a local cinema. My big break with my brother’s skiffle group. They had a guitar player called Laurence Sheaf, who had a gut-string acoustic and used to emulate exactly Big Bill Broonzy. And I used to sit there and he’d play “Guitar Shuffle”: “Wow, man!” He’d just blow my mind, and that’s when I said, “I want to play like that!” I’d like to have been in the audience watching Big Bill Broonzy on this old video I have of him from Belgium. He’s a younger man. It’s all dark, and it’s got this swinging lamp shade and drinks and cigarettes and close-ups on him. Oh, it’s wonderful. And my first paying gig, in my local town near Heathrow Airport, was with Memphis Slim. I got a bottle of whiskey for it, and I was about 16. It was called the Ivy Leaf Club.

How then did you first find fame as a bassist?

When my first band, the Birds, split up, I had reached a saturation point on the guitar. I thought, “It’s not going anywhere.” I used to meet Jeff Beck on the road, and when he left the Yardbirds, I just rang him up. He said, “Hey, come over. Let’s form a band.” So the Jeff Beck Group was my first break on the bass. But I used to do sessions on it, as well, like Arthur Brown’s “Fire,” “Goo Goo Barabajagal” with Donovan. A lot of them.

Were you aware of Big Jim Sullivan?

Yeah! He had all the jobs. He had control. He was the man. Him and Jimmy Page were the top session men in England at the time.

When did you cross trails with the Rolling Stones?

At the outset. During the Cyril Davies era, Charlie Watts was the drummer, and my brother Art used to help Charlie’s dad set the drums up for him. One day Charlie said to Art, “I’ve got this offer to join this interval band called the Rolling Stones” – like they played during the interval between big bands, you know. He said, “I don’t know whether to do it or not.” And Art said, “Go for it!” Charlie didn’t know what to do, because he was a commercial artist, as well, as my brothers were, and I was gonna go that way as well.

One of the first times I bumped into Mick and Charlie was at Hyde Park, when Brian had died and they were doing a concert. I was walking around the perimeter, and Charlie and Mick came across the road in front of me. We said hi, and they said, “We’ll see you soon.” I said, “Yeah, sooner than you think!” Thinking one day I was gonna be in that band. Yeah.

After Mick Taylor left, you helped kick the Stones to a whole new level.

Mick Taylor always underestimated himself. He didn’t think he could play the guitar, which I always used to tell him he was totally wrong about. Some nights he had so much stage fright when he was in the Gods that I had to go on and do his set. He was just too nervous to go on. I’d go on and play with this band I never played with before and do his set, then I’d go do my set with the Birds.

What were Mick Taylor’s strengths?

In his actual playing. He hasn’t changed that much. A few years ago when I had Woody’s on the Beach in Miami, a club where I got to play with all my favorites – you know, Buddy Guy and all those – I had Mick Taylor’s blues band there. I got up and played with him, and then when it came to doing an encore, he said, “I can’t go on. You do it.” It was exactly the same as the old days! I said, “Mick, what the hell is going on?”

You seem to have so much fun when you’re playing. It’s almost like that’s your high.

It is, yeah. I do feel very comfortable playing.

Are you a compulsive player?

No. I very rarely play when I’m on my own. I’m into playing with people – when I’m with Keith or Eric or even with Slash or Izzy [Stradlin]. You know, it don’t matter. We swap licks and just play. And Mick Jagger as well. Mick’s got a good rhythm style.

If one of your kids wanted to play guitar . . .

Like Jesse James, who’s arriving in a couple of days.

Would you suggest learning from records?

Well, I would have said record schooling, like I did, learning straight from the record if you’ve got the ear. But nowadays they have these guitar schools. As an option to further education in England, you can either go to university or to a special course for your A levels, or you can study the guitar at these schools. Not too long hours – just three or four hours a day, they go – and that’s what Jesse’s doing. It’s really improved his playing. He’s been blowing my mind, because he plays it a lot like Steve Cropper. The great thing is he never came to me for any shortcuts or tips or anything. He did it all on his own. I’m very proud of him. I did sit him down with Eric once and just left him alone in the room. He was very nervous, and I was listening outside. We’ve jammed together. He’s got a band now called Wood Spirit, which is the strongest alcohol you can get, as well. Blow your head off!

Do you collect vintage instruments?

Yep. Got old Uncle Harvey, my Dobro. I bought it from John Dopyera, one of the Dopyera brothers [founders of Dobro]. It’s very special. It’s downstairs. It’s a gold-plated and wooden Dobro. In fact, Mick’s playing it on “The Storm,” which is the B-side of the first single, “Love Is Strong.”

What’s it like touring at 50?

Even more fun. You just can’t wait to get out in front of the audience again and give ’em your best.

What’s the most challenging aspect of the Rolling Stones gig?

Trying to remember where the breaks come in songs. Like [imitates someone yelling at him] “Oh, Woody! You better stop now!” But that’s all fun, as well. You get that out in rehearsals, make all the mistakes.

During the rehearsal of “Heartbreaker” last night, you copped Mick Taylor’s solo after one listen. Quick study.

Yeah. That’s where I’m lucky. Blessed! By the way, that was an alternative set last night – none of those are in the set we’re gonna do.

Keith has described your playing relationship with him as being very intuitive, where one subconsciously covers the other.

Yeah. We don’t talk about where we stop and play. We just get on with it. I’ve that relationship with other musicians – Buddy Guy, Muddy Waters – but not as fluidly as it is with Keith. Muddy, he’s the boss, the daddy of ’em all. I love the way he did everything. The man! Another one is Hubert Sumlin, who I met in New York. He came back to my house, and we played all night. He’s fantastic. I love that man, and I love his playing with Howlin’ Wolf, you know.

Are you working on any outside projects or is it a total commitment to the Rolling Stones?

It’s total, really.

Do you do anything special to keep your sanity on the road?

I take these Chinese herbal pills called reeshee, which give you some energy. It’s like pill food for the brain. I do a little bit of general working out – a bit of running and swimming – and generally just enjoy the playing.

You’ve had a wonderful career.

I know. I wouldn’t change a thing. It’s great. It’s been brilliant.

###

For more on the Rolling Stones:

Charlie Watts: Our Complete 1994 Interview

Talking Blues With Keith Richards

Mick Taylor Interview: Inside the Rolling Stones

Help support the Talking Guitar project by becoming a paid subscriber or by hitting the donate button. Thank you!

© 2023 Jas Obrecht. All rights reserved.

Ronnies playing is stunning on the Stones' IMAX production! A blinder as they say! And even more stunning is his bass playing on his 2 albums with Jeff Beck!

Saw Ron Wood with Beck and Rod the Mod

Start of the Rock Era

Jas have read you for decades