During my 47 years as a music journalist, I’ve bylined more than 150 cover stories. Many of these were penned for Guitar Player during the magazine’s so-called “Golden Era,” which ran from the mid-1970s to the early 1990s. I’ve bylined dozens more for other music magazines published in English, French, German, Spanish, Italian, and Japanese. This two-part article tells the backstories for a dozen of my favorites, presented in chronological order from 1978 to 1995. Click on the underlined passages to view transcriptions of the interviews and/or hear the original audio.

In the spring of 1978, I was living in a duplex on Detroit’s West Side, and the situation seemed dire. From my front porch, I could point to houses up and down the street where murders had recently occurred. I’d never open my door to strangers after dark. Most houses had bars on the windows.

Every weekday morning I drove downtown to my first editorial gig, writing biographies for Gale Research’s Contemporary Authors series. I talked the higher-ups into letting me write a detailed bio of Doors singer Jim Morrison, who’d published an evocative volume of poetry called The Lords and the New Creatures.

Anxious to escape the crime and low pay, I sent my resume to Guitar Player magazine. I attached a Xerox-copy of the Morrison piece, the only article about a musician that I’d written, and a bio of e.e. cummings.

Guitar Player’s Editor, Don Menn, liked what he saw and arranged for me to fly to San Jose, California, for an interview a few days later. A few hours after arriving in late April, I was hired. That evening Don brought me to his home in Palo Alto for dinner. Little did we imagine that the little girl running around the living room, Don’s daughter Gretchen, would grow up to become a beloved, world-renowned guitarist.

The magazine wanted me to start immediately, so I flew home, watched movers pack my belongings and ’68 VW into the back of a truck, and caught a plane back on May 4 – Ascension Thursday. As soon as I arrived, suitcase in hand, Don asked me to write my first record review.

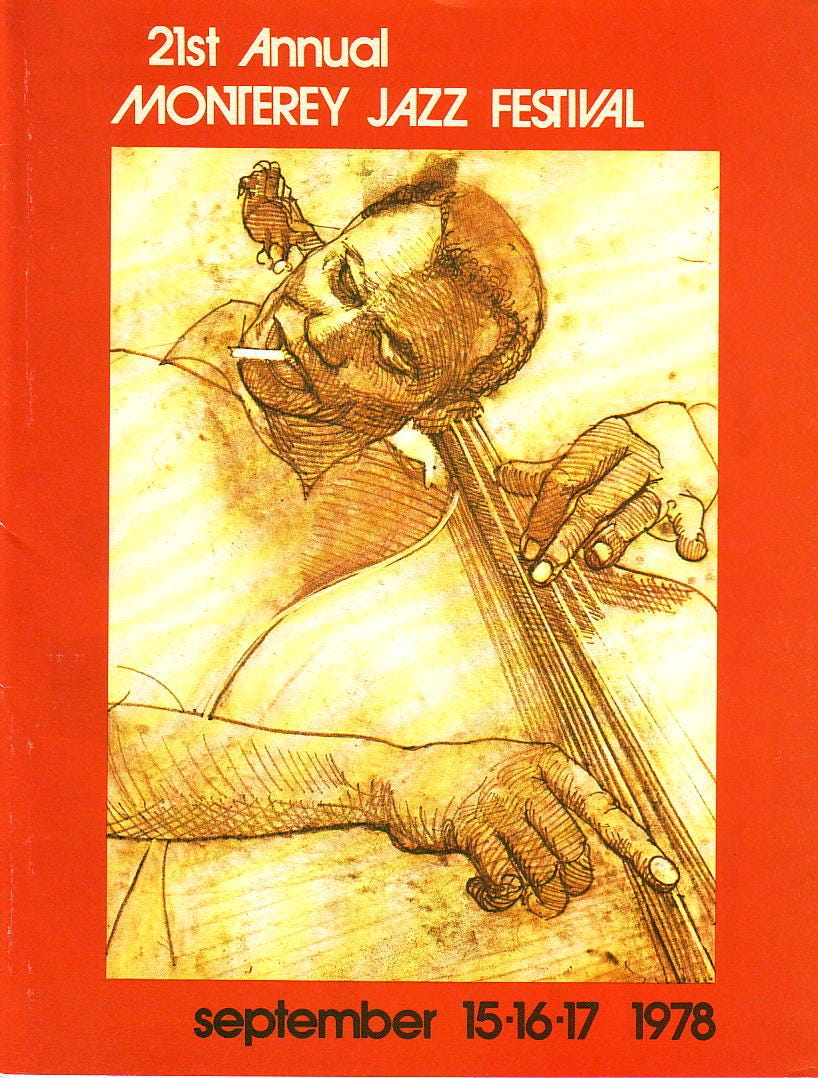

The next morning he called me into his office and asked, “How’d you like to make $600 freelancing for the Monterey Jazz Festival?” $600 was more than two month’s rent, so yeah! He explained that our company, GPI Publications, had been hired to produce the festival’s magazine-style program. The assignment: write all the bios of the performing musicians. I borrowed armloads of books from GPI’s library and got to work writing bios of Dexter Gordon, Dizzy Gillespie, Milt Jackson, Ray Brown, Kenny Burrell, Maynard Ferguson, Billy Cobham, Etta James, Ruth Brown, Clifton Chenier, and many others. It was my first freelance gig. My contributions filled half of the magazine. Susan Dysinger was commissioned to create the Ray Brown illustration that graced the cover.

In September I made the pilgrimage to Monterey to watch the Saturday performances from stageside. My favorite memory of the event is a half-hour spent backstage talking with Dizzy Gillespie and Ray Brown. Dizzy, in a wonderful mood, was especially welcoming to the newcomer with the brand-new press pass.

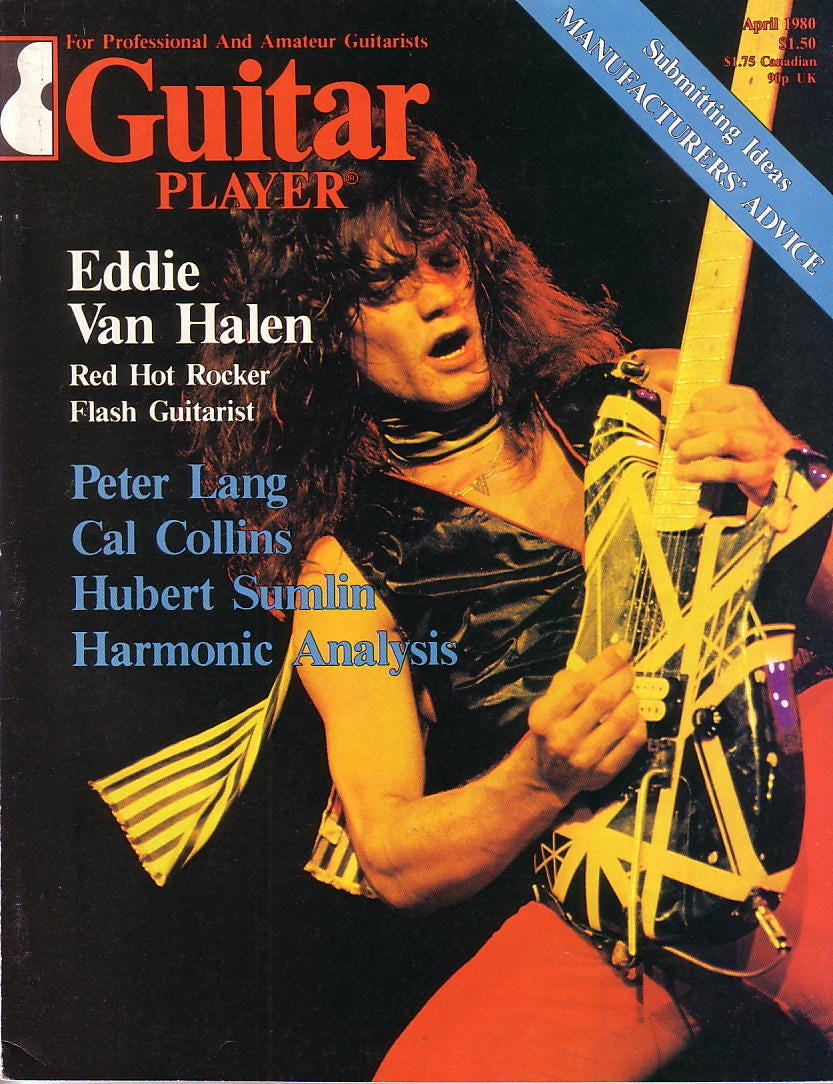

My April 1980 cover story with Eddie Van Halen was actually his idea. I’d done his first-ever interview, which he always appreciated, and he trusted me. At the tail end of a 1979 phone interview, Eddie told me that for him appearing on the cover of Guitar Player would be “a dream come true.”

I flew down to Hollywood a couple of weeks later and we ended up spending about eight hours together at Neil Zlozower’s photo studio. Eddie had agreed in advance to talk about his groundbreaking techniques, so he brought a couple of his guitars to the interview. The one I remember best is the homemade electric guitar now known as the “Frankenstrat.” When I first played it in 1978, Eddie had spray-painted it white and created black stripes using electrician’s tape. By the 1980 interview, he’d refinished it with red paint. He played it unamplified as he demonstrated his techniques, favorite Clapton solos, and parts of Van Halen songs.

In those days drugs were fairly commonplace in interviews with rock musicians. By then Eddie was already well into consuming cocaine. That’s how he jumpstarted the interview, which began around 10:00 AM. I didn’t join him in that particular endeavor, but after lunch I asked if he’d like to join me for a joint. “Hey, I have one,” Eddie replied. He reached in his pocket and pulled out an old-fashioned wallet that had plastic inserts for credit cards.

The only contents in that wallet were his driver’s license and most of a partially smoked joint. He lit it up, and we each took a toke. I remember the surprised look on Neil’s face as he mentioned that he’d never seen Eddie smoke before. Eddie put the rest of the roach back in his wallet. Almost immediately he became woozy—to the point where he had to sit down. “Dave smokes all the time,” he said, “and I don’t know how he does it. I just can’t do it.” When Eddie recovered, we proceeded to shoot the hands-on-the-guitar photos that appear in the magazine.

As Eddie drove me back to the airport for my late-afternoon flight, we got stuck in a long line at a traffic light. He flashed me an impish smile, said “Hold on, man!,” jumped the curb, and raced his four-wheel drive across the front lawns of several houses. We landed on the cross-street, turned right, and sped off. The whole time I was thinking, “If we get pulled over and Eddie has to show his license, we’re going to jail.” But hey, who better to go to jail with in 1980 than Eddie Van Halen?

That April 1980 magazine became the era’s fastest and best-selling issue of Guitar Player. I’ve posted several hours of the audio on my Talking Guitar YouTube channel, including sections where he’s playing the unplugged Frankenstrat. Here’s a link to the first part: Eddie Van Halen: The Complete 1980 Interview - Tape 1.

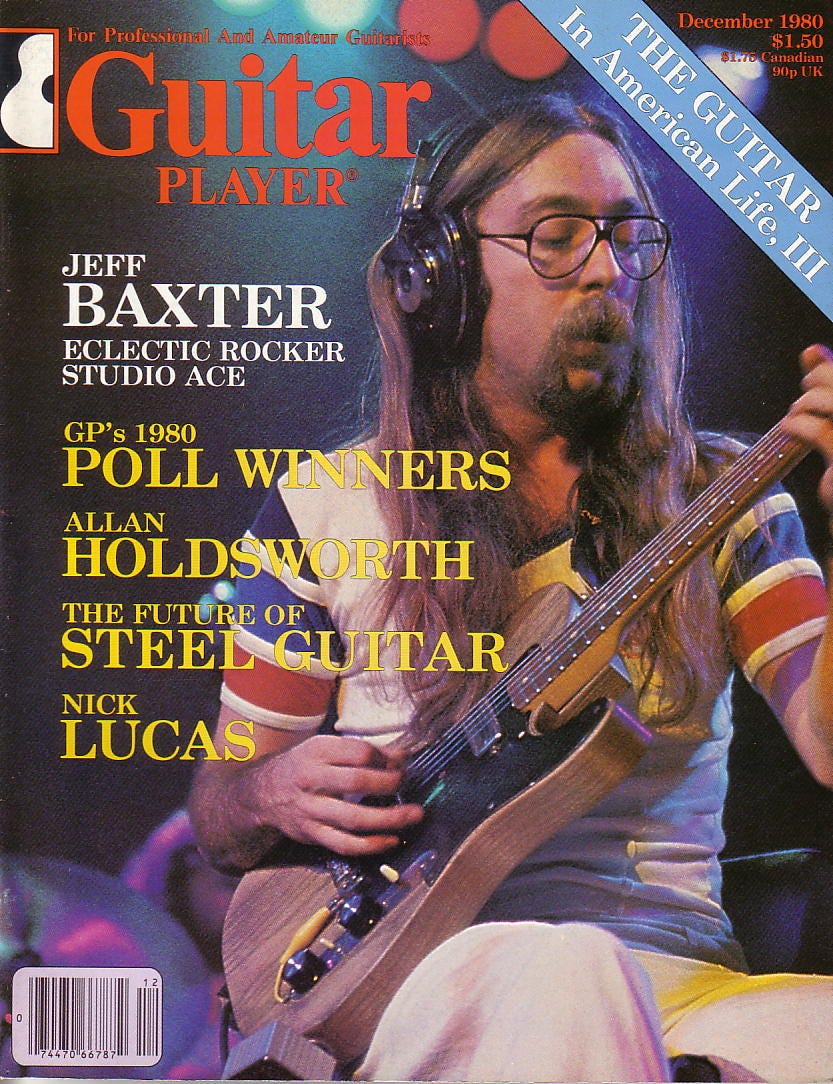

I love Jeff Baxter’s playing. Always have. His solos, then and now, are among the most spectacular on record. One of my first assignments at Guitar Player was editing his monthly column. Sometimes he’d write them out, sometimes he’d dictate them to me over the phone.

Given Jeff’s high profile with the Doobie Brothers and Steely Dan, as well as his accomplishments as one of L.A.’s top studio sharpshooters, he was a natural choice for the December 1980 cover. I was delighted to be given the assignment.

At the time, Jeff had a spacious home atop the Mandeville Canyon section of Los Angeles. As I recall, Ronnie Wood lived next door. When I arrived on a sunny morning, Jeff greeted me warmly, invited me in, and we got right to it.

After an hour or two, we decided to take a break. One of us brought up the idea of getting stoned—I forget who—and I pulled out a joint. Jeff said, “No. Let’s smoke some of mine. It’s really good.” He led me into a room that had pinball machine and a deep freezer. He opened the freezer, pulled out a large bag of weed, and twisted one up. We passed it back and forth and relaxed for a while

When time came to resume the interview, I asked Jeff something and he launched into a long, involved response. When he finished, my mind went completely blank—the only time that’s ever happened in an interview. He grinned at me knowingly and said, “I told you it was strong!” Skunk.

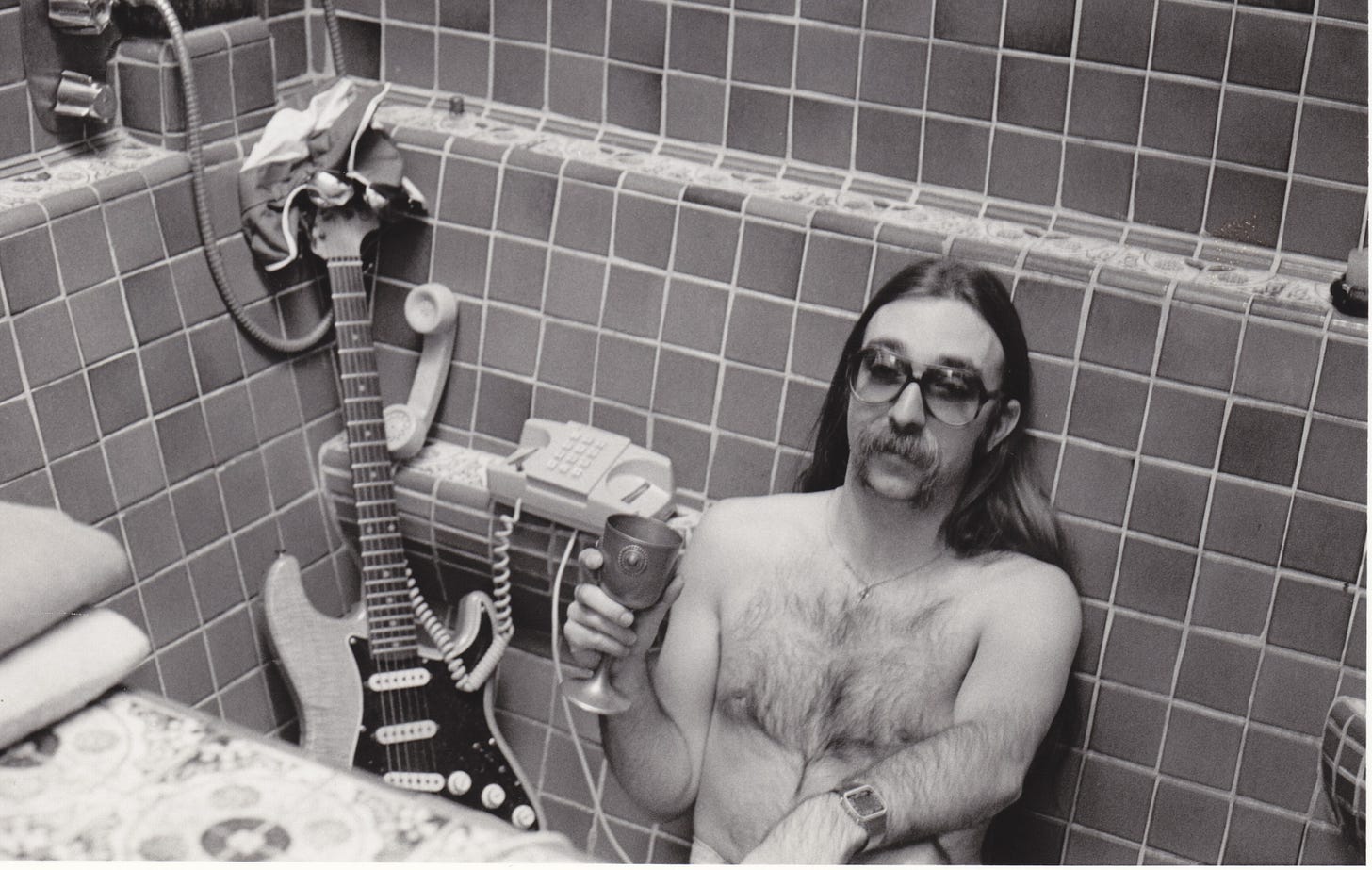

I’d brought along a Nikon camera, so we decided to take some photos. Jeff suggested we do a few in his jacuzzi, with him holding a wine goblet while his Stratocaster negotiated a deal over the phone. He peeled off his shirt, grabbed a phone and a guitar, climbed into the empty jacuzzi, and set up the shot. Exhibit A:

After that, Jeff led me to his guitar room to show me his instruments, including his Strat with a see-through Lucite body. I was astonished to learn that he had not one, but two archtop guitars crafted by legendary New York luthier John D’Angelico. The one I remember best was a gorgeous New Yorker. Noticing my reaction, he graciously handed them to me one at a time. Magnificent sounding guitars! This was the first and only time I’ve ever played an early D’Angelico, although I later saw another one up-close in Tommy Tedesco’s den.

After our cover story came out, Jeff called my publisher, Jim Crockett, to tell him how much he enjoyed the article and the interview experience. To this day, hearing Jeff Baxter play guitar always brings a thrill. And going by his recent YouTube videos, he plays as well today as he did back then. What a guy!

As soon as I heard Are You Experienced in 1967, Jimi Hendrix became my favorite musician. After he passed away, I felt a void, as did many others. A few weeks later one of the guys in my dorm told me about the Allman Brothers, describing them as “the best damn band in the land.” One listen to their albums, and I was hooked. Then we heard Derek & The Dominos’ Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs, which featured more of Duane’s spectacular soloing, both bare-fingered and with a bottleneck.

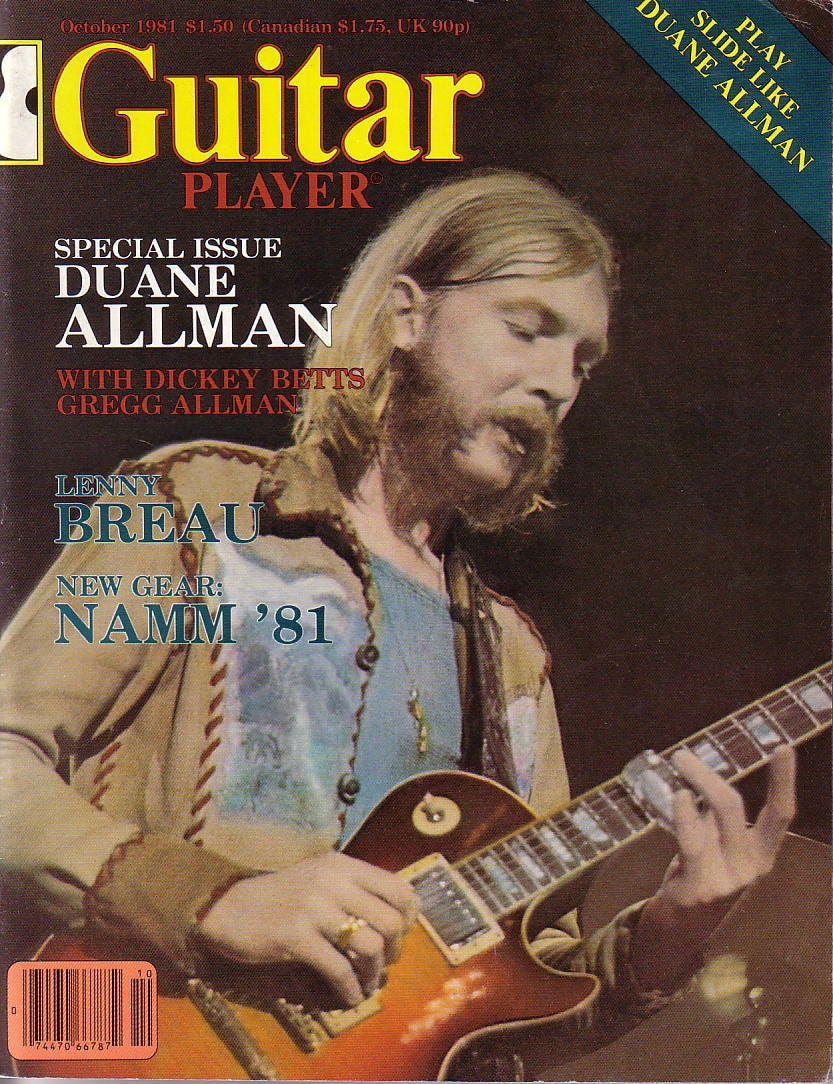

With the tenth anniversary of Duane’s tragic death approaching, I asked our newly appointed Editor, Tom Wheeler, if I could do a tribute in the October 1981 issue. Tom, who had a profound love for guitar music, not only agreed, but said, “Duane Allman?! Let’s make it a special issue!” I was given carte blanche to fill as many pages as I wanted—and the time to do it. In those days, Guitar Player was always good about that.

I reached out to musicians who’d worked alongside of Duane. To a man, everyone agreed to be interviewed: Gregg Allman, Dickey Betts, Pete Carr from the Hour Glass, Billy Gibbons, Duane’s best friend John Hammond, and David Hood and Jimmy Johnson, who’d worked with Duane at Muscle Shoals Sound Studio. (I also tried to find Duane’s boyhood friend/guitar teacher Jim Shepley and Bob Greenlee, who led the first bands Duane and Gregg played in, but was unable to locate them before the deadline.) Tom commissioned Arlen Roth to write a musical analysis of Duane’s slide style. Jim Marshall, who shot the iconic front and back covers of the Allman Brothers’ At Fillmore East, agreed to provide us with photos.

Due to deadline constraints, all of the interviews were done by phone. The one with Gregg was especially poignant (hear it here: Gregg Allman: The Complete “My Brother Duane” Interview, 1981). He was unabashed in his admiration of his older brother, and by the end of our conversation he was choked up. In fact, everyone I spoke to held Duane in very high regard. Months later I finally located Jim Shepley and Bob Greenlee, and we spoke at length about Duane as well. (Transcriptions: Young Duane Allman: The Jim Shepley Interview and Young Duane Allman: The Bob Greenlee “House Rockers” Interview.)

About six months after the issue was published, Guitar Player’s secretary rang my phone to inform me that Gregg Allman was on the line. “I just wanted you to know that you did a real fine job on that magazine,” Gregg told me. “I gave a copy to my mother, and she’s kept it displayed on her coffee table ever since.” R.I.P. Duane, Gregg, and mama Geraldine.

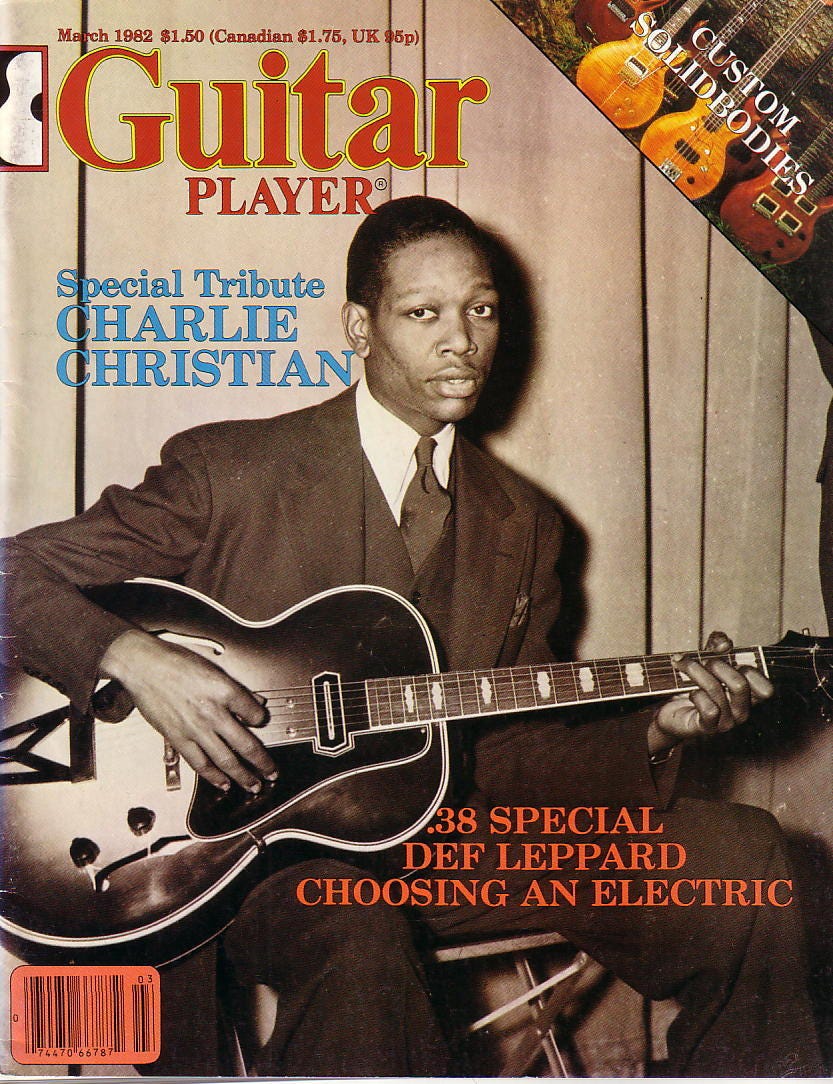

While most of my fellow Guitar Player editors tended to be deeply interested in the gear side of things—guitars, amps, and effects—for me, it’s always been about how the player thinks, composes, and finds inspiration. And few players have sparked as much inspiration or caused such sweeping changes to the guitar’s basic vocabulary as Charlie Christian.

Like Robert Johnson and Jimi Hendrix, Charlie was one of these rare musicians who burns incandescently for a relatively short while and then disappears from this earthly realm. With the success of the Duane Allman issue, Tom Wheeler was happy to greenlight my proposal to do a special issue on Charlie Christian. After all, Christian was and still is the single most important figure in the history of jazz guitar. Players today continue to draw inspiration from his sound, note choices, and finesse. Rightfully so.

Among my responsibilities at Guitar Player was editing monthly columns by Jeff Baxter, Michael Lorimer, Tommy Tedesco, and Barney Kessel. Through his columns, which he hand-wrote on lined yellow legal paper, I was well aware that Barney Kessel, a famous jazzer in his own right, was a dedicated disciple of Charlie Christian. With that in mind, I called Barney and told him about my idea for the special issue. He immediately insisted that he had to be a part of it.

When the time came for our interview, he was raring to go. It was one of those rare interviews where I barely had to ask questions. Barney knew what he wanted to say and took control of our conversation. I was happy to let him do it. (You can hear it here: Barney Kessel: The Complete 1981 “Charlie Christian” Interview.) It turns out Barney not only appreciated Charlie’s music, but had met and jammed with him. If you’re into Charlie Christian, jazz guitar, Davy Crockett hats, hula hoops, or the history of the electric guitar, Barney’s insights are a must-hear.

Christian had made his mark in the late 1930s and early 1940s as a member of Benny Goodman’s sextet. Benny’s brother-in-law, famed Columbia producer and talent scout John Hammond, had “discovered” Charlie playing in Oklahoma City. Hammond brought him to Los Angeles to audition for Benny Goodman, leader of the era’s most famous swing band.

At Barney’s suggestion, I called Columbia Records in New York and left a message for John Hammond (father of Duane’s friend John Hammond). Finding Benny was a bit more challenging. Unable to get a lead from a record label or the Musician’s Union, I finally called information—which in those days meant speaking to a long-distance operator to request someone’s phone number.

An operator in Manhattan informed me that she had no listings for a Benjamin Goodman, but six numbers for “B. Goodman.” I asked for all six. On the second try, an elderly gentleman answered the phone. I said, “I’m calling for Benny Goodman.” “You got him,” came the response. “The bandleader?” “Yep.” Benny Goodman had a listed phone number! A day or two later, we did a brief but insightful interview. (Here’s the audio of that call: Benny Goodman Remembers Charlie Christian and Sings One of His Solos.)

Meanwhile, I’d been having difficulty getting a response from John Hammond, and deadline was fast approaching. As soon as I got off the phone with Benny, I thought I’d give him one more try. When I told his secretary at Columbia that I’d just spoken to Benny, she said “Just a moment.” Seconds later John Hammond picked up the phone. Here’s what happened next: Columbia Records’ John Hammond Remembers Charlie Christian.

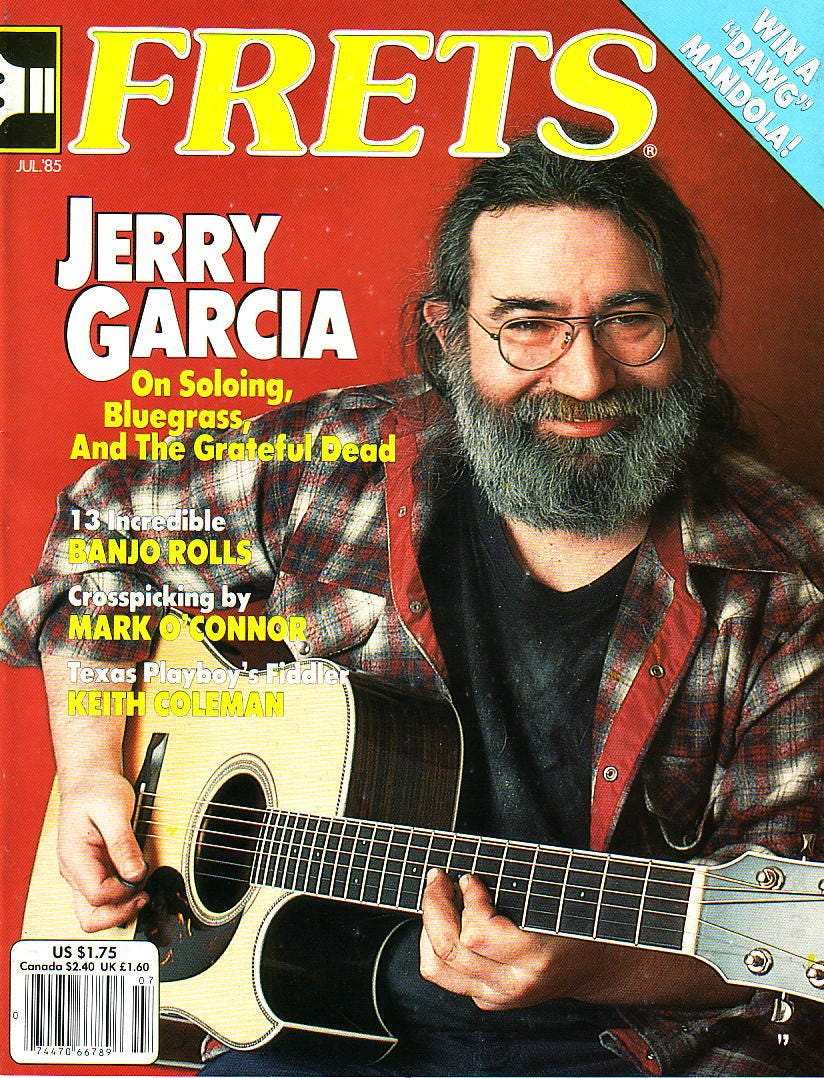

Guitar Player was GPI Publications’ largest-circulation magazine. Its “sister publication,” the brilliantly written and edited Keyboard, was the go-to publication for anyone who played piano or keyboard synthesizers. In the early 1980s Jim Crockett decided to launch a third magazine devoted entirely to acoustic music played on stringed instruments—guitars, banjos, violins, cellos, etc. He named it Frets, and it quickly caught on with bluegrass and classical players. Frets Editor Phil Hood enlisted me to write a monthly column called “Acoustic Roots.”

During the mid-1980s the Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia was doing a lot of side gigs playing acoustic guitar. To celebrate the Dead’s 20th anniversary, I proposed that Frets do a Jerry Garcia cover story. Phil gave it the go. Jerry liked Frets magazine, but getting him to sit down for the interview proved challenging. On at least three occasions band publicist Dennis McNally called me to cancel the scheduled interview.

Jerry finally agreed to a sit-down on January 12, 1985. As fate would have it, I already had another cover story interview scheduled that morning, with Yngwie Malmsteen, who’d just released Rising Force. After meeting with Yngwie in a San Francisco hotel, I drove over the Golden Gate Bridge to someone’s home in San Rafael and met with Jerry in the early afternoon.

Jerry sat down in a chair across from me. He locked eyes with me and seldom looked away as he spoke, rapidly answering questions. I remember being grateful in the moment that I was an experienced interviewer, because I had the feeling that if I looked down at my questions I might lose his attention.

A while into the interview, Jerry pulled out a sizable rock of cocaine and nonchalantly chopped it into lines. He did not offer any to me or the others in the room—photographer Jon Sievert and freelance writer Lissy Abraham, who had volunteered to write the intro to the Frets piece. I’d seen people snort coke before, but I was surprised by the amount and the speed at which Jerry ingested it. The only musician I’ve ever seen rival his intake was Leslie West, but that’s a story for another day…..

Despite the drug use, Jerry impressed me with the sheer incandescence of his mind throughout the day. He was articulate, insightful, forthcoming, genial, and, frankly, a pleasure to be with. (Here’s the audio: Jerry Garcia: The Complete 1985 “Frets” Interview.)

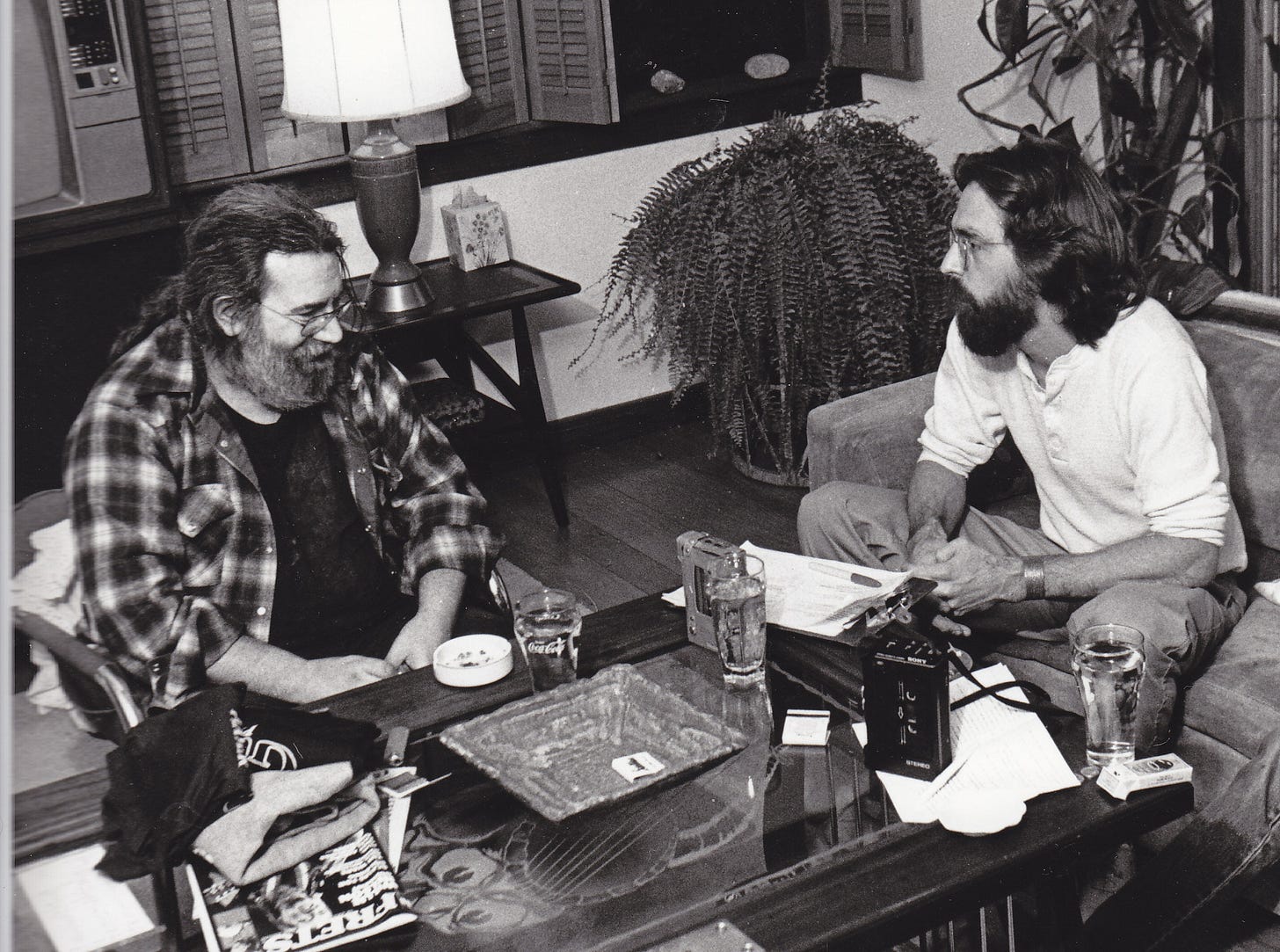

It turned out that Jerry did not have a guitar at the house he was staying at, so Jon Sievert went to a nearby music store and borrowed the instrument seen on the cover. I snapped this photo as Jerry played it for us:

A few days after this interview Jerry Garcia was busted for freebasing in his car in Golden Gate Park.

A Garcia side-note: Two years later, Jerry came to GPI Publications to sit in on one of our monthly jam sessions. At the time I was putting together a poster of famous players’ guitar picks, and I asked Jerry if he had an extra. He pulled a Dunlap 2mm graphite plectrum from his pocket. Before he handed it to me, he looked at it wistfully and said, “You know, sometimes I think that this is the only thing standing between me and abject poverty.”

###

Stay tuned for Part 2.

###

Thanks to Nik Hunt for helping with the graphics.

To help me continue producing articles such as this and podcasts of guitar-intensive interviews, please become a paid subscriber ($5 a month, $40 a year) or hit that donate button. Paid subscribers have complete access to all of the 130+ articles and podcasts posted in Talking Guitar. Thank you for your support!

©2024 Jas Obrecht. All rights reserved.