Note: Some of the interview sources quoted in this series preserved the speakers’ Jamaican patois, while others presented their words in more standardized English. I’ve stayed true to the way the words originally appeared in print, hence the differences in the phrasings of Bob Marley and others.

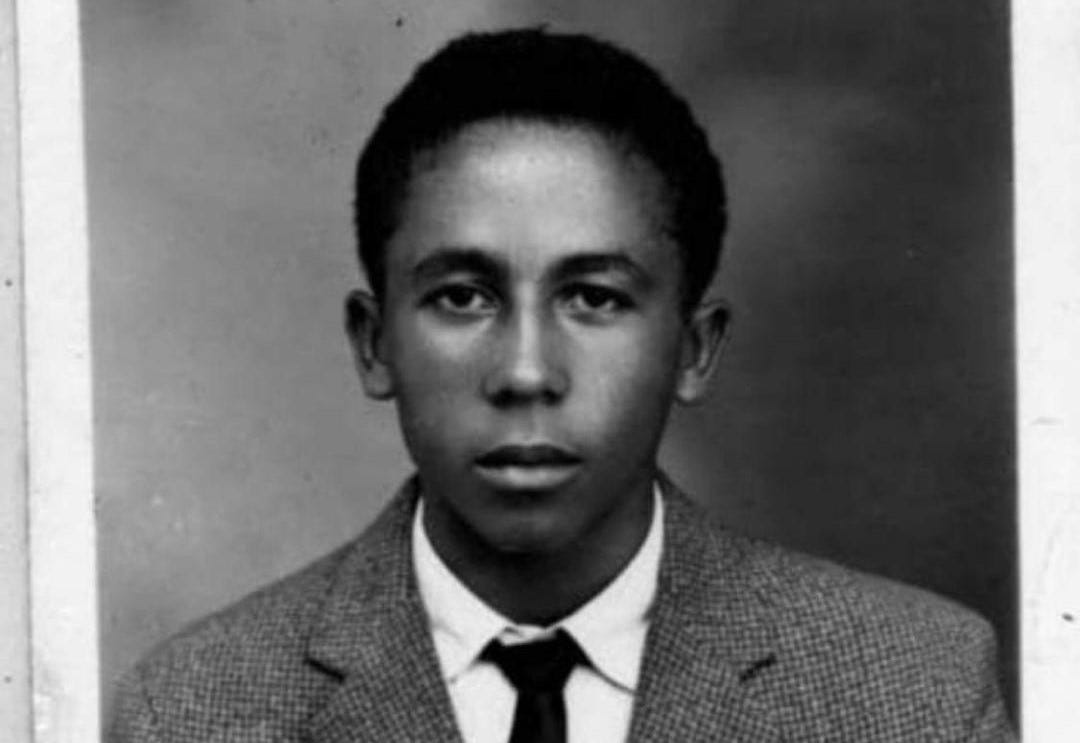

Bob Marley’s music transcends politics, language, cultures, borders, and the passage of time. Equally suitable for the prison yard and the cathedral, his songs speak to the oppressed, the broken-hearted, seekers of spiritual enlightenment, and celebrators of life.

As Charles Shaar Murray wrote in Crosstown Traffic, “Marley developed into possibly the most extraordinary figure in the history of Western pop culture: not only the acknowledged leader of his chosen musical idiom, but the world’s most prominent spokesman for a religion previously unknown to almost all but its practitioners, and finally the most politically influential recording artist of the 20th century.” Four decades after his death, Bob Marley is still listened to around the world and revered as a national hero in his homeland.

During Marley’s lifetime, his influence left an indelible imprint on Jamaican contemporaries such as Dennis Brown, Gregory Isaacs, and Burning Spear, to name but a few. His first notable disciple outside of Jamaica, Eric Clapton, turned a respectful cover of “I Shot the Sheriff” into an international hit in 1974, scoring his first #1 single in the process. “Bob Marley was a wonderful songwriter and a great rhythm guitarist,” Clapton said. “He was just an amazing musician.” Marley’s inspiration soon resounded in artists ranging from the Police, Elvis Costello, and the Clash to Paul Simon, Joe Jackson, and Stevie Wonder, who wrote “Master Blaster” as a tribute to him. Marley’s influence endures to this day.

For Carlos Santana, among others, Marley’s imprint has been as much spiritual as musical. “Bob Marley was a champion liberator,” Santana says, “because his songs liberate us from our own personal demons, and you thank God that you have ears and a heart to take it in. It’s so precious. Marley is supremely important for his divine message of one love, which is the equivalent of the message of Martin Luther King and John Coltrane’s ‘A Love Supreme.’ ‘One love’ means no popes, no pimps, no gurus, no swamis, no government, no church or anything like that. One love is all of us being spiritual enough to complement life. We all heal each other. We all mend a broken heart. We all lift up somebody who falls. Bob Marley shows the supreme balance of being so close to God and so human at the same time.”

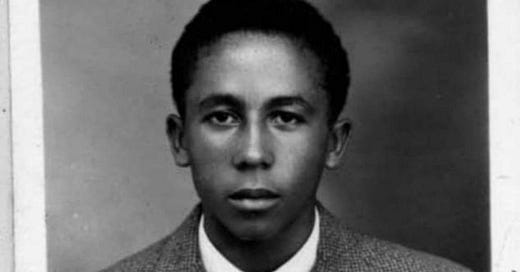

He was born Nesta Robert Marley on February 6, 1945, on the farm of his maternal grandfather, Omeriah Malcolm, near the village of Nine Mile in St. Ann’s Parish, Jamaica. Eight months earlier, Bob’s mother, Cedella Malcolm, had married his father, Norval Sinclair Marley. “I was about seventeen and livin’ in St. Ann when I met Bob’s father,” Cedella explained in Stephen Davis and Peter Simon’s Reggae International. “He was a handsome white man, in his fifties, a captain in the Army who worked as a foreman over the Army property contingent, a place for people who are back from war. You see, Jamaica wasn’t independent then, and the British Army was still there. St. Ann was farm country, a beautiful place, but Norval was not a farmer. He was a soldier.”

The day after the wedding, Norval Marley departed to work in Kingston. He returned for Bob’s birth, but soon left again, leaving Cedella to fend for her infant. Nevertheless, Cedella had fond memories of her husband: “To me, he was a good man,” she revealed in her memoir Bob Marley, My Son. “I was very young, but he was always loving. He was very affectionate. And anybody ask him, he would give them money from his pocket and things like that. Everybody in the district sort of looked up to him.”

Until Bob was six, he and his mother shared a small shack in the lush, mountainous countryside. “He was my first-born and very precious to the family and friends.” Cedella wrote. “He was always a jolly, happy little young man. He loved to make friends, loved to play. I never had no trouble with him going to school and things like that. He was very obedient, very cooperative as a little boy.”

While Cedella ran a small grocery store, selling homegrown produce, her son found a father figure in his grandfather, Omeriah Malcolm: “He would always be up early with his grandfather,” Cedella explained. “He liked to ride the donkeys out into the field. He liked to milk the cows, milk the goats, to feed them.” In an interview near the end of his life, Marley fondly recalled his days on the farm: “Me grow up in it, you know. That’s the first thing me ever do – farming. My grow up in it and it is me really love. But the farming I used to do, it was slave farming with the machete and a hoe. Or we dig it by hand. We didn’t have dem t’ing that you drive and plough it up.”

Around 1951, Captain Marley returned to Nine Mile and convinced Bob’s mother and grandfather that the boy could receive a better education at a boarding school in Kingston. Months later, a friend who’d just returned from Kingston told Cedella that she’d spotted Bob on the street. Traveling the 75-mile bus journey to Kingston, Cedella discovered that rather than enroll Bob in school, Captain Marley had loaned him out to serve as the caretaker for an elderly woman named Mrs. Grey. Diabetic and barely able to ambulate, Mrs. Grey implored Cedella to allow the seven-year-old to continue to care for her: “Without Nesta,” she told Cedella, “I can’t even get food from the market.” Furious with her husband’s behavior, Cedella immediately returned to St. Ann with her son. Asked about his father decades later, Marley responded, “I only remember seeing him twice, when I was small.”

Upon his return to St. Ann, Bob was enrolled in school and began showing an interest in music. “I don’t really know how I got started,” he reported in 1975, “but I know me mother was a singer. Me mother is spiritual, like a gospel singer. She writes songs. I hear her singing first and then I just love music, love it, grow with it.”

Bob drew further inspiration from more secular sources: “I preferred dancing music. I listened to Ricky Nelson, Elvis, Fats Domino. That kind of thing was popular with Jamaican kids in the Fifties. The only English-speaking radio station we heard was from Miami, but we got a lot of Latin stations, mostly from Cuba, before and after Castro.”

A cousin gave him his first instrument, a guitar fashioned of bamboo and goatskin. Bob befriended another Nine Mile youth who shared his interest in music, Neville “Bunny” Livingston, who’d later adapt the name Bunny Wailer. “They were like brothers,” Cedella recalled. “When you see one, you see the other. They were always together.”

In 1955 word reached Bob that his father had died. At that time, Cedella wrote in her memoir, “We were living hand-to-mouth, battering from pillar to post.” During a visit to St. Ann, Cedella’s brother John, who owned a house in Kingston, offered her a position as housekeeper. After discussing it with the family, Cedella left Bob in the care of Omeriah Malcolm and moved to Kingston. She worked a variety of low-paying jobs to send clothing and food back home. When her Aunt Ivy offered Cedella and Bob the opportunity to move into her apartment on Beckford Street, Cedella sent home for her son.

Cedella and Bob frequently moved during their first two years in Kingston. They finally settling into a two-bedroom, two-story dwelling at 19 Second Street in the infamous west-side ghetto known as Trench Town. Their government-subsidized concrete dwelling opened out into a shared common area – a “government yard,” locals called it. Built over the drainage ditch from which it got its name, Trench Town was rife with poverty, disease, malnutrition, and violence. It also had a vibrant music scene.

Years later, Bob immortalized his experience living there in one of his best-loved songs, “No Woman, No Cry”:

’Cause I remember when we used to sit

In the government yard in Trench Town

Observing the hypocrites

Mingle with the good people we meet

Good friends we had

Good friends we’ve lost, along the way

In this bright future you can’t forget your past

So dry your tears I say

No woman no cry…

In 1974, Marley cited this as one of his favorite songs: “Me really love ‘No Woman, No Cry,’ because it mean so much to me. So much feeling me get from it. Really love it.”

Young Bob attended three schools in Kingston. Cedella remembered him coming home after classes one day and singing the gospel song “In the Garden.” “I was stunned at how well he sang. Nesta had always been a singing child, but this is the first time I can remember being struck by his beautiful singing voice.” He made his first public performance in a talent show at a local theater.

In 1960 Bob Marley reunited with his childhood friend Bunny Livingston, who’d moved to Trench Town with his father, Thaddeus “Taddy” Livingston. The Livingstons moved in with the Marleys, and Cedella and Taddy had a daughter together, Pearl Livingston. Their sons, meanwhile, immersed themselves in music.

Bunny crafted himself an instrument: “When I was a yout’ I used to play a homemade guitar,” he reported in Reggae International. “I took the strings for it from some electrical wire—electrical wires ’ave fine wires inside. I took the rubber off them and used the fine wires. I took a sardine can, nailed it to a piece of wood, and the bamboo pole was the neck of the guitar. At the time Bob and I were living together on Second Street in Trench Town.” The boyhood friends initially practiced singing calypso and American R&B songs together. They were also drawn to “ska,” a new sound emerging right in their own neighborhood.

Most ska music was instrumental, with the after-beat played on rhythm guitar or piano. Ernest Ranglin, the “daddy” of Jamaican guitarists, explained that local musicians originated the term “ska” to “talk about that skat! skat! skat! scratchin’ guitar strum that goes behind.” Ska typically featured a fast rhythm accented by horns riffing on the off beat. The style drew from the syncopated mento style popularized in the 1940s and contemporary R&B records, especially the sound of New Orleans, with its horns, boogie piano, and strong bass.

Ska songs were broadcast on the radio and heavily featured in local open-air dances known as “sound system.” These were typically staged by record shop owners and disc jockeys who blasted songs through large PA systems. Producers often supplied sound system disc jockeys with acetates of just-recorded songs to test their marketability. If audiences raved, the songs were issued as seven-inch 45s days later.

Around age 14 Bob dropped out of school. His situation at home became increasingly fraught as tensions rose between his mother and Taddy. Cedella described one telling incident in her book: “Nesta, who was about 15 years old at the time, was very angry and upset when he saw me with a black eye. ‘When I grow big, Mamma, and become a man,’ he vowed, touching my bruised eye, ‘I’m goin’ lick dat man back inna him eye. You wait and see.’ ‘No,’ I said wearily, ‘you don’t have to do dat. You’ll just bring more trouble.’ And Nesta never did.”

Bob and Bunny began spending time with Joe Higgs, who lived near them on Third Street. Higgs owned a guitar and gave free voice lessons out in the yard. Well versed in the subjects of jazz, R&B, and Jamaican styles, Higgs tutored Bob and Bunny in the art of singing close harmony and the rudiments of song construction. “We looked up to Joe Higgs,” Bunny explained. “He was something like a musical guardian for us. He was a more professional singer, because he was workin’ for years wit’ a fella named Roy Wilson as Higgs & Wilson. They had a lotta hits and they had the knowledge of the harmony techniques, so he taught us them.”

Higgs introduced his pupils to another young musician, Peter “Tosh” McIntosh, and encouraged them to form a singing trio. In addition to having a strong baritone, Tosh possessed a battered factory-made acoustic guitar. “I always played an instrument – see, I was the beginning,” Tosh would later tell an interviewer. “Before I played guitar, I played piano and organ. I teach Bob to play the guitar. Yeah, mon!”

With Bunny singing the high parts, Bob handling tenor, and Tosh providing baritone, they practiced songs such as Sam Cooke’s “Chain Gang” and “Wonderful World,” Ray Charles’s “Hit the Road, Jack,” and the Impressions’ “Gypsy Woman.” “In the start,” Bunny explained, “it was jus’ Peter Tosh, me, and Bob Marley—nobody else. We jus’ sat around in quiet places in Trench Town and harmonized. Dis was the period when we nicknamed de Wailing Rudeboys or the Teenagers, but we never recorded with these names.” Tosh added, “Me and Bunny together had a kind of voice that could decorate Bob’s music and make it beautiful, so we just did that wholeheartedly.”

Soon after Tosh joined Marley and Livingston, a youth loaned Bob an acoustic guitar. “We hold on to that guitar for a good period of time,” Tosh recalled, “until I teach Bob to play it, and show Bunny some chords.” Joe Higgs also taught Bob some basic guitar chords. “When I started singing, I couldn’t play an instrument,” Marley explained. “How I learn to play guitar? I teach myself. Well, it grow together. The first time me try to write a song is the first time me try to play the guitar. So it really grow together. Me really like to stay with my guitar, but me never really take the guitar playing seriously.”

Meanwhile, Bob’s mother found him a day job: “I knew men who were doing welding for a livin’, and I suggested that he go down to the shop and make himself an apprentice. He hated it. One day he was welding some steel and a piece of metal flew off and got stuck right in the white of his eye, and he had to go to the hospital twice to have it taken out. It caused him terrible pain. It even hurt for him to cry.”

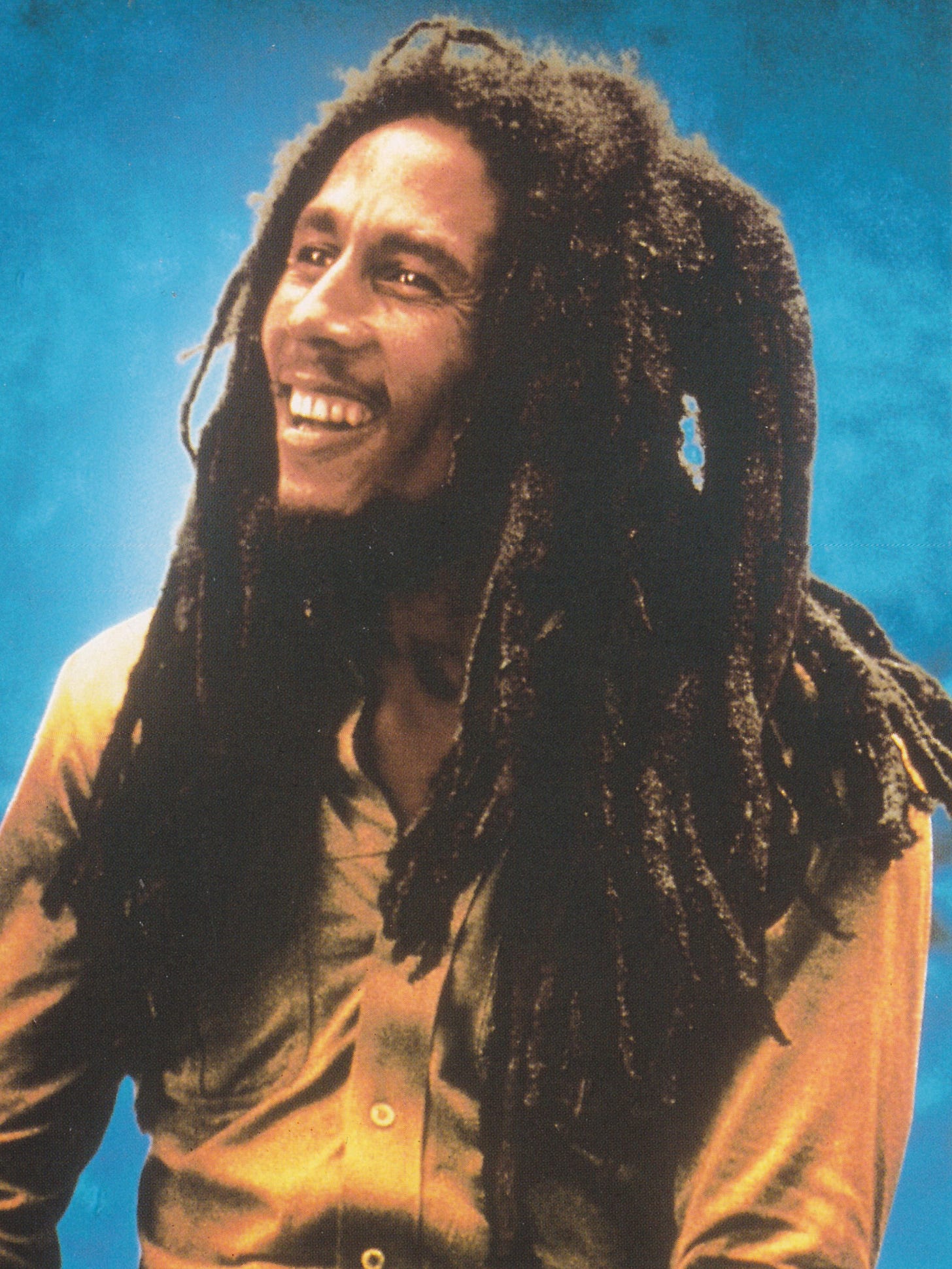

One of the workers Bob sang with around the welding yard, Desmond Dekker, encouraged him to pursue his dream of making records. “Me did sing in school and love singing,” Marley explained, “but what really made me take it seriously is when I go and learn a trade name welding. Desmond Dekker used to learn trade [at the] same place, and we used to sing and him write songs. . . . Him go check out Beverley’s [an indie record label] and him do a thing named ‘Honor Your Mother and Father,’ which was a big hit in Jamaica. After that, him say, ‘Come, man,’ and me go down there and meet Jimmy Cliff and him get me audition…. I loved to sing, so I thought I might as well take a chance. Welding was too hard! So I went went down to Leslie Kong at Beverley’s Records.”

Bob found the audition at Federal Studios to be challenging: “I meet Leslie Kong at Federal. I was looking for [producer] Count Boysie, and Desmond Dekker say I should check out Leslie Kong. And dat man rude! Tell me to sing my song straight out, standing outside. Didn’t have no guitar, rass-clot. Dat focker!” Despite the rocky audition, Kong, a 29-year-old Chinese-Jamaican record producer, saw potential in a pair of Bob’s ska-style songs.

In February 1962 he supervised the 17-year-old’s very first recordings, at Federal Studios. Marley’s lyrics for “Judge Not” were inspired by one of his grandfather’s sayings, “Judge not, before you judge yourself”:

Don’t you look at me so smug

And say I’m going bad

Who are you to judge me

And the life that I live?

I know that I’m not perfect

And that I don’t claim to be

So before you point your fingers

Be sure your hands are clean

Judge not

Before you judge yourself

Judge not

If you’re not ready for judgement, woah oh oh

His lyrics for his second number, “Do You Still Love Me?,” could easily have served as an inspiration for the Clash’s “Should I Stay or Should I Go”:

Do you still love me like you used to do?

’Cause it’s a pain away, there’s another for you

Tell me, my darlin’, so I may know

If I must leave, stay or go

Accompanying Marley on both songs were the “Beverley’s All Stars,” a studio band featuring drummer Arkland “Drumbago” Parks, bassist Lloyd Brevett, guitarist Jerome “Jah Jerry” Haines, harmonica player Charlie Organaire, and tenor saxophonist Roland Alphonso, among others. (The identities of the pianist and the musician playing the flute and/or recorder melodies remain unconfirmed.) Followers of the Rastafari faith, Alphonso, Brevett, and Haines would become founding members of Jamaica’s premier ska band, the Skatalites.

“Kong must pay for the studio time for me,” Bob recalled of his debut session. “So I sing and Kong pay me two £10 notes and then push me out. When I say to him, ‘What if it a hit?’ him say, ‘Coo pon’ [i.e., “pay attention”], and say I’m trying to wreck the deal. Mon-a name-a Dowling [“a man named Dowling”] make I sign a release form, them then push me out a studio and I run home. First I wait for acetates, then I run home.”

First issued as Beverley Records LM 027, the 45 credited “Robert Marley” as the performer and “R. Marley” as the composer of both songs. About two months later, Bob returned to Federal Studios to record another pair of songs with Beverley’s All Stars, the unissued “Terror” and “One Cup of Coffee.” Upon its release, Kong identified the artist as “Bobby Martell” and incorrectly assigned the “One Cup of Coffee” songwriting credit to B. Marley. (About a year earlier, Claude Gray’s recording of the Bill Brock composition “I’ll Just Have a Cop of Coffee (And Then I’ll Go)” had reached #4 in Billboard’s Country and Western chart.)

Neither of Bob Marley’s debut 45s were promoted or garnered radio play. But they did launch Marley’s recording career and help him realize an early musical ambition: “Me just wanted to hear myself over the jukebox.” His singles were subsequently reissued in England by Chris Blackwell’s fledgling Island Records. It would be another two years before Bob Marley would record again.

Coming soon: “Bob Marley: The Early Years (1962-1966): From Trench Town Ska to the Wilmington Blues”

More Bob Marley:

Donald Kinsey On Playing With Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, Albert King…

Aston “Family Man” Barrett on Bob Marley and the Bass in Reggae

###

Help me continue producing guitar-intensive articles and podcasts by becoming a paid subscriber ($5 a month, $40 a year) or by hitting that donate button. Paid subscribers have complete access to all of the 165+ articles and podcasts posted in Talking Guitar. Thank you!

©2024 Jas Obrecht. All right reserved.

So good to hear about harmonizing “in a quiet place “ and the sardine can guitar!