Donald Kinsey: On Playing with Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, Albert King . . .

In 1985, Donald Kinsey Reflected on His Extraordinary Musical Journey

By age 23, Donald Kinsey had already assured his place in music history, having played in the bands of Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, and Albert King. His credits for 1976 alone include Peter Tosh’s Legalize It and Live and Dangerous albums, as well as Bob Marley’s Rastaman Vibration and Live at the Roxy. In short, Kinsey, master of the poignant guitar solo, has one of the most impressive blues and reggae resumes imaginable.

Son of bluesman Lester “Big Daddy” Kinsey, Donald was born in 1953 and raised in Gary, Indiana. Playing with his father’s revue, he became known as “B.B. King, Jr.” At 18, he was hired to go on the road with blues great Albert King, who featured him on his classic Stax albums Blues at Sunrise, Blues at Sunset, I Wanna Get Funky, and Montreux Festival. Donald’s next project, the short-lived power trio White Lightnin’, was signed to Island Records, which led to his celebrated stints with labelmates Peter Tosh and Bob Marley. Between 1976 and 1984, Kinsey went on several tours with Tosh, including opening for the Rolling Stones in 1978, and he accompanied Tosh on six albums. He became a full-fledged member of Bob Marley and The Wailers in 1976 and, as he describes below, was in the room the night Bob Marley was shot by would-be assassins. Three years later, Donald joined the reggae legend’s final tour.

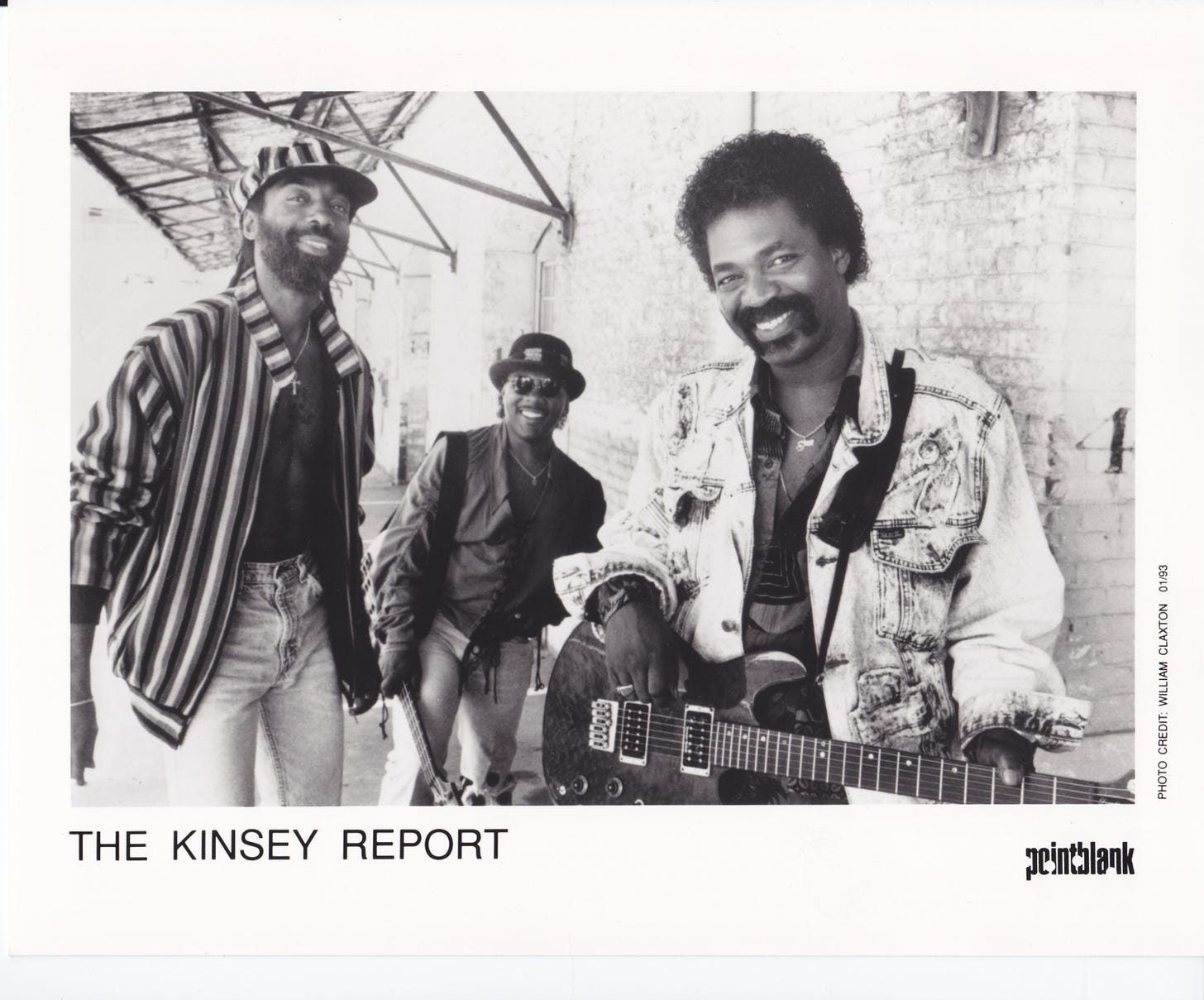

Since the mid 1980s, Kinsey has devoted himself to playing alongside those who share his family name. He’s recorded albums with his father and the Kinsey Report, which features his brothers Ralph on drums and Kenneth on bass. Our interview took place in Gary, Indiana, on August 1, 1985. At the time, Big Daddy Kinsey’s first album, Bad Situation, was about to be released.

###

How does it feel to be back playing the blues?

I’ll tell you, it’s a good feeling. It really is. I was deep off into the reggae scene for a minute there. It was refreshing and almost regenerating coming back and playing the blues. Being here at home in the Midwest really, really, really did me wonders within myself.

When did you come back to the Midwest?

It’s been two years. Man, we were on the road for almost eight months out of the year with Peter Tosh on that Mama Africa album. We toured all of Europe and we went to Africa. When we were in France, and even before, I was noticing there was something happening with the blues. It seemed like it was coming alive more. You would see more of it on TV. You would see artists. You would hear it on the radio. It was like it was coming alive again. My father, who put the guitar in my hands, he’s been really consistent with me. I called him, and I told him that the vibe just felt right, as far as my feelings go, for him to work on his first album. So I just told him that when I come back home, I wasn’t going to go back out on the road with nobody else or do anything, that I was gonna really spend some time working with him trying to get an album out there. So that’s what we did, and it just so happens that the timing and everything just was perfect, because Peter hasn’t done anything since.

When was your last album with Peter Tosh?

The Mama Africa album – that album was maybe two, three years ago at the most.

You co-wrote all of the songs on your dad’s album.

Yeah. Normally how we work as a family is I might come up with a basic structure, and might even have a melody, but I might not have one word. I make a tape of whatever it is I have for my dad or brother. Or vice versa – they’ll do the same thing. We’re very creative musically, and usually the music is almost the first thing. We might have a concept of where we want the song to go. It was dad’s album, so we were writing for it to really fit dad. He had to be a part of everything, you know.

Like the “Nuclear War” tune, for an example. We picked a topic that was a now topic. It just so happened that his father was still living. His father was in World War I, my father was in World War II. I didn’t go into the service, but my brother Ralph, he was also in the service. So we just took it a little more recent than that and just said, “Well, my son is in Lebanon,” you know. It’s always a group effort. We always get together at my father’s house. Downstairs we have a little four-track system set up, so it’s like headquarters.

You’ve played with your brother Ralph in a few bands.

Yeah. First of all, it was White Lightnin’. We did an album on Island Records [called White Lightnin’]. That came about after me playing with Albert King. When I was with Albert, I met this bass player who goes by the name of Buster Jones. During that time my brother Ralph was in the service. He came home, and then the three of us got together. We put together a three-piece. It was rock and roll – kind of like heavy metal.

Lot of solos?

Right, right. It was good. And it was bluesy. I can’t think of anything that I’ve done, man, that wasn’t bluesy. We came here to Gary, and we got together. We started writing the material and just shooting stuff around, trying to see what our sound would be as a three-piece. We were using big chords and heavy solos. There’s something about three-pieces – I used to really check out a lot of Cream – and I was interested. “Mississippi Queen” was one of my favorite tunes, by Mountain. And then also playing with Albert King taught me a lot. It helped me at that particular time, because I was going through that period where I was thinking speed was it, as far as soloing and really trying to get something across. But Albert and a lot of people helped me grab my heart, man, and slow down a little bit. Then I was more into delivering something that would be easier for people to catch on to, something that they can carry with them in their memory.

Did you learn that from Albert King?

Yeah, Albert. Every now and then he would give me solos, you know, and one day we was on the bus and he just came to me and said, “Hey, when you solo, slow yourself down.” He said, “Those people out there in the audience, by the time they are getting ready to leave from that concert, they not gonna remember anything you done. You’re not gonna leave them with a feeling. It’s better for you to utilize four or five notes in some type of melody that can really connect with the people than to play 150 notes within a solo.” And it kind of made sense to me. I just took that and tried to mold it into something. It done me good. I try to play more with the melody type of form, where the solo is almost a vocalist type of situation.

What should a Donald Kinsey solo do?

It should enhance whatever the song is all about musically. It should be like an icing on the cake and not change the flavor of the cake. Yeah.

Talking Guitar is a reader-supported publication. Every paid subscription helps ensure that this work continues.

Did you play any solos on Albert’s I Wanna Get Funky and Montreux Festival albums?

Yeah. Let’s see. On the I Wanna Get Funky album, I don’t know if you’d call it an actual solo, but I did the slide work on the “I Wanna Get Funky” track, and the slide is kind of dominating that song. On “That’s What the Blues Is All About,” I’m doing the wah-wah track on that, the rhythm. “Till My Back Ain’t Got No Bone” – there’s slide on that one too.

Did you play the wah-wah on the Montreux album?

Yeah, I’m playing the wah-wah. On the last cut, when we’re going out, I’m actually the one that’s ending the album. You know, after he goes off during “For the Love of a Woman.”

Did Albert ever give you playing advice, like how to bend notes?

No. It was something that I already had, because they used to call me “B.B. King, Jr.,” when I was like 15 years old.

I’d heard about that. How did you get the name?

[Laughs.] My father was a B.B. King man – he liked B.B. King. Every time B.B. King came through town, my father would be there, if he was available. He has a lot of photographs of him and B.B. King around. And I used to listen. I was one of those types of guys that would put the record on. My father, if he wanted me to learn a song, man, he’d get me a record and say, “Here. You sit here for this record.” And I would learn it until I had it. My father used to be playing, like, “Johnny B. Goode” type of things, as far as rock and roll was concerned, on the guitar. And so I would pick up on stuff like that. But as far as really blues, I heard a lot of B.B. King when I was younger, and Muddy Waters and Lightnin’ Hopkins.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Talking Guitar ★ Jas Obrecht's Music Magazine to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.