Milt Gabler: On Recording Classic Jazz and Rock’s First #1 Hit

A 1981 Interview With the Producer of 40+ Million Sellers

During his six decades in the music business, Milt Gabler produced hundreds of beloved jazz and pop records. His triumphs include the Kansas City Six’s historic jazz sides, Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit,” and Louis Jordan’s “Choo Choo Ch ’Boogie,” which he co-wrote. Then, in 1954, he produced Bill Haley’s “(We’re Gonna) Rock Around the Clock,” the first rock song to reach #1 in the pop charts. By his own reckoning, Milt Gabler was responsible for more than 40 million-sellers.

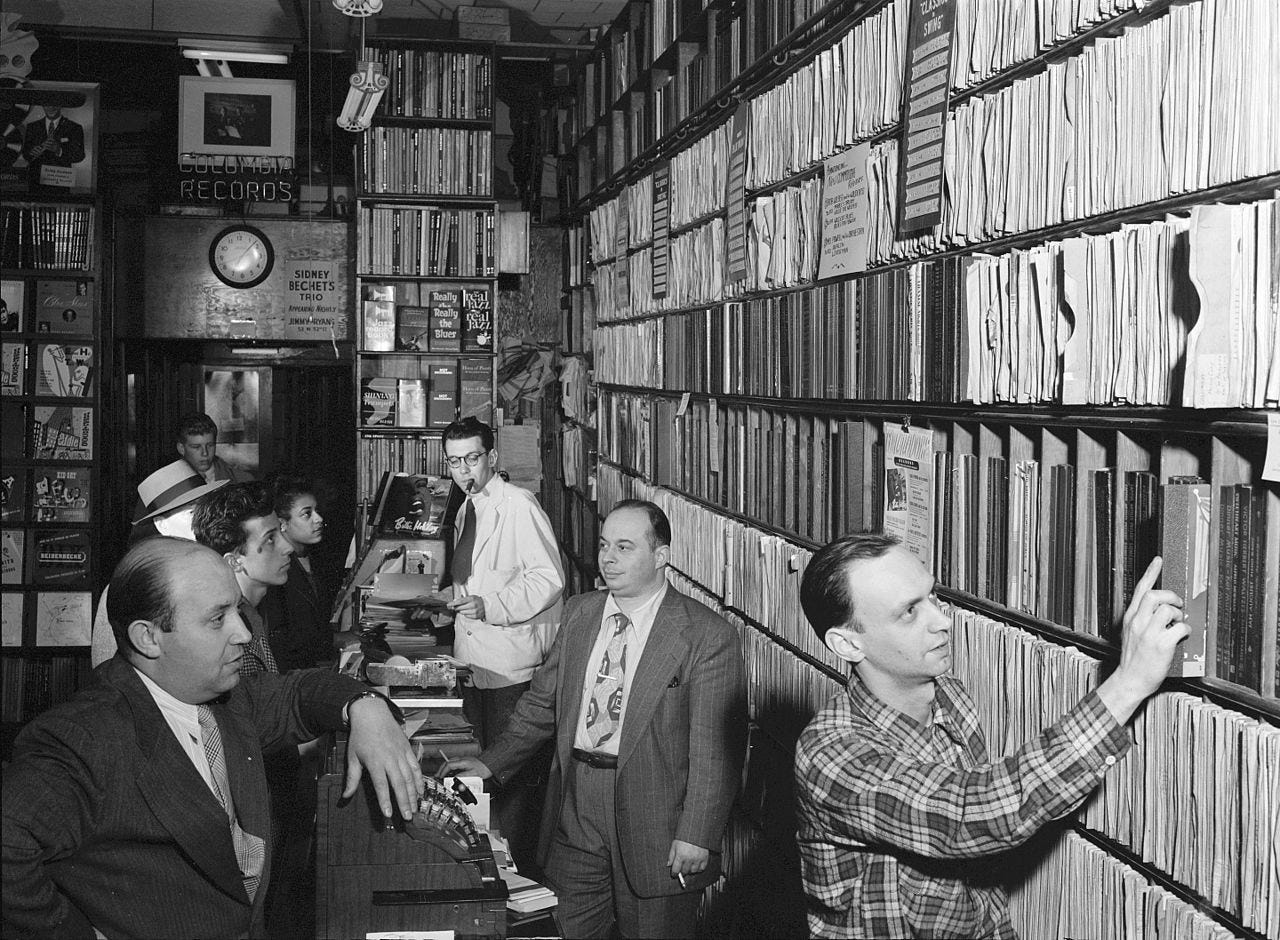

Born on May 20, 1911, in New York City, Milt began his retail career working in his father’s 42nd Street store. During the 1930s he opened his own store, the Commodore Music Shop, on 52nd Street in midtown Manhattan. He couldn’t have chosen a better location. Swing music was in its ascendancy, and the street had such a vibrant club scene it was nicknamed “Swing Street.”

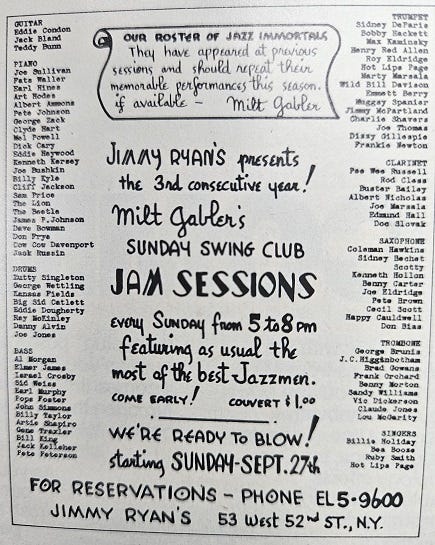

To fill his store shelves, Gabler initially bought unsold stock from record labels stateside and abroad. He and Marshall Stearns created the United Hots Clubs of America to promote the sales of jazz records. Launching his own Commodore record label and securing licensing deals, Gabler became a pioneer in reissuing records. His innovative mail-order service expanded his reach. Held for many years at Jimmy Ryan’s at 53 West 52nd Street, the weekly “Milt Gabler’s Sunday Swing Club Jam Sessions” attracted a who’s-who of pre-war jazz greats.

In 1941 Gabler joined the staff of Decca Records. He initially oversaw the reissuing of Brunswick and Vocalion releases before being promoted to the head of A&R. During the ensuing three decades, he produced hits by Louis Jordan, Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong, Lionel Hampton, the Andrews Sisters, Andy Kirk, Jimmie Lunceford, Billie Holiday, the Weavers, the Mills Brothers, the Ink Spots, Peggy Lee, Brenda Lee, and many others. When MCA acquired Decca in the mid-1960s, Milt stayed on to oversee reissues. He retired in 1971.

A decade later, I sought out Milt and asked if he’d be willing to discuss New York’s pre-war jazz scene and how he recorded the first #1 rock single. He graciously agreed. An edited version of our Q/A appeared as in the August 1981 issue of Guitar Player magazine; below is a complete transcript.

###

In 1926, you opened your first retail store.

Right.

How old were you then?

I was born in 1911, so that makes me 15. Well, actually I was working for my father. He had an electrical and hardware store and took in radios, you know, after World War I. When radio came in, we were kids, and we lived behind the store. I went to Stuyvesant High School because it was near the store and I used to go there after school.

How broad were you musical tastes by then?

Oh, at 15? It would just be popular songs of the day.

Were your parents interested in music?

Well, they liked music. You know, the popular music. They used to go, I found out later, to opera once in a while. We had a phonograph, a crank machine, in the house, and they had popular artists, classical symphonies, and cantorial records and stuff like that.

Did you learn to play any musical instruments?

No.

When did your interest in jazz begin?

Well, we didn’t call it jazz in those years when I was a kid. The popular dance music I used to dance to would be similar to Dixieland—you know, small bands. The first live music I heard was like a jazz band trying to play pop music for dancing.

Who were the best-known early jazz guitarists?

Eddie Lang, Dick McDonough, and Carl Kress were the first three big white guitarists. With black guitarists, you had the blues players like Lonnie Johnson.

Could you trace a genealogy of jazz guitarists who became popular afterwards?

Boy, that would take a little thought because you’re talking of rhythm guitarists and guitarists who took solos. With rhythm players, you would have to include Eddie Condon, even though he played a 4-string. He would give the guys right chords and keep the band straight. Of course, when the dance bands came in, all the good guitar men were playing rhythm. Freddie Green never soloed; he was with Count Basie. It wasn’t much sense to play solos with acoustic guitars unless the guitarist was sitting right by the mike.

In the early days of recording direct to wax or disc, the banjo and then the acoustic guitar was mainly used as a rhythm instrument. Fingerpicking was used on blues, folk, and occasionally pop music recording, and definitely on country-style accompaniments.

The amplified solo added a whole new dimension. Guitarists were able to speak for themselves the same as the others in the band because for the first time they were able to be heard above the din of the room. In my record shop Django Reinhardt was very popular on acoustic, but soon the American players overtook him as they were here in the U.S. and, I feel, more adventurous. Tal Farlow with Red Norvo was one of them.

Who were the first to record jazz solos with an electric guitar?

The fellow I used on the Kansas City Six records, Eddie Durham. They’re the first ones I know of on electric guitar. We only used one mike on those sessions, and Freddie Green played acoustic. That was 1938. Charlie Christian came after that. Charlie was a front-runner and an innovator. He really made it popular. The thing is, the instrument had just come out then. Durham was the first guy to experiment with it. They were just building those amps and things then. Christian came in right with that, right on top of that. When was Charlie’s first records with Benny?

1939.

Yeah, well, the others we did were ’38, so he started to get the instrument right away. Durham, being really a trombonist/arranger, was into something else, but he was experimenting with it. You know, the solos he played on those Kansas City Six records aren’t that great, but they are there. They are solos. They are the first ones I know of on electric guitar.

What was the energy like in the 1930s when Swing Street started happening?

The energy? What do you mean by energy?

Was it an unexpected new musical direction, and did it bring about a new image for musicians? You read about it now, and it seems like it brought in a whole new lifestyle.

Well, that would be the end of the ’30s and the ’40s. In the early ’30s, you had the crooners and bands like [Paul] Whiteman and [Fred] Waring and stuff like that, hotel bands. The jazz musicians were buried in those bands. It wasn’t until just below the mid-’30s that guys started to play around the 52nd Street area—I can only speak for New York, you know. At Plunkett’s and stuff like that, the Whitby Hotel. Guys started to sit in.

When the networks moved to Radio City and CBS was on 52nd and Madison, the prohibition bars along 52nd Street had guys like [Art] Tatum and [Joe] Sullivan playing piano. And guys would carry their horns and go for a drink and sit in. That would be around the mid-’30s. I was already into jazz by that time, because when I got in the OKeh records—the Ellingtons and the Armstrongs and the Red Nichols records—that was the kind of stuff I liked. And the [Eddie] Condon stuff that was made at the end of the ’20s. I didn’t know Eddie then. I met him in the early ’30s, when he came to New York. That was jazz, to me, and I started featuring it in the Commodore shop. Of course, I couldn’t compete with the big fancy shops on selling symphonies and a lot of records. I specialized in the ones that I liked.

Was it strictly jazz records?

No, I sold everything in the world. When we first started, it was just pop records.

When you started Commodore Records, who were the guitarists featured on your releases?

Well, you would have Condon, Al Casey, Jimmy McLin, Freddie Green. We didn’t do too many guitar solos. Let’s see. I did [Coleman] Hawkins, Chu Berry, Roy Eldridge. On all the Dixieland-type records, I always had Eddie [Condon] on guitar. On the others, some of the bands didn’t have guitar in them. We would use rhythm without guitar. But I always liked the sound of a guitar in there to add color to the afterbeat of the high hat. The high hat had no note to it, so I used to mike my rhythm guitar so it would give it a more mellow sound. You’d hear the guitar chord rather than just the high hat.

By this time were there multiple microphones?

No. Well, there were multiple mikes in the sense that essentially on a jazz date you would use two microphones. We’d group the rhythm section around the piano—you know, bass, guitar, and piano—so that we could open that mike in case the pianist took eight bars or sixteen bars or a full chorus. Otherwise, you would just crack it and get your rhythm. And all the other guys played around the main mike.

Were any of the musicians intimidated by recording or by the studio?

Hell, no.

Leonard Feather mentioned that in 1936 you sponsored a concert for Bessie Smith.

That was one of the jazz sessions we had on 52nd Street. It wasn’t a Bessie Smith concert—she came to sing! They weren’t called “concerts.” They were just called jam sessions. And we invited the public. Teddy Wilson was at that concert. I think Bunny Berigan was there. Of course, Eddie and the guys.

I started to move them [the jam sessions] into nightclubs to save the money of taking over and getting a super to open the building and renting 150 chairs, you know, and not having any booze for the people that came. If I did it in a nightclub, they would sell booze to them. They would give me the room for nothing, and the drums would be there because at night there was a group working there. It was much easier and more homelike. Of course, we couldn’t get as many people in, but no admission was charged either.

It was after that session that Bessie Smith sang at that the Hickory House found there were so many people there on a summer day, on a Sunday, that went to the Hickory to hear Joe Marsala that night. They said, “Where the hell did all these people come from?” Well, they were the people that hung around. They went over there to get a steak or to eat, and waited for Joe to start to play. Then they got a WNEW wire and Wingy [Manone] went in there, and they started a broadcast from the Hickory House. They had jam sessions every Sunday. Ralph Burton started to have them down in the Village, and he started charging a dollar admission. And the musicians weren’t getting paid. When Pee Wee [Russell] told me he worked Burton’s and he didn’t get any money, that’s when I started running them commercially at Jimmy Ryan’s. Then I charged a dollar and I had to give ten cents of it to the IRS as an admissions tax.

What would a jamming musician make?

In those years? Ten or twelve dollars an afternoon.

Were jam sessions racially mixed?

Yeah, right from the beginning. And all my recordings.

In 1941, Jack Kapp invited you to join Decca.

Yep.

What was your capacity with Decca through the years?

Well, I went from a guy that was hired…. I got him to buy the Brunswick/Vocalion records that were owned by Warner Brothers and lying fallow. Up to 1932, they were unavailable. I wanted to reissue a record—that’s how I found out about it. Columbia wouldn’t press it for me. I always thought they had the rights to it. It was “Pinetop’s Boogie Woogie.” They wouldn’t press the record for me after I’d advertised it in Down Beat. The legal department stopped the Custom Division, and they said, “We don’t own this record.” So they called me and said they can’t make the record. I said, “Damn it. I got it advertised!”

I knew that Jack Lapp, who was president of Decca, was originally head of A&R for Brunswick/Vocalion in one of his capacities. So I called up Jack, and he said, “Oh, I know all about those records. They belong to Warner Brothers.” So I said, Well, if you get the rights to them, I’ll come up and reissue them for you.” So he worked it out. Decca bought the rights, and then he called me to come and work for Decca. It was November of 1941.

How long did you stay with Decca?

Thirty years.

And then you retired ten years ago?

[Laughs.] I was asked to retire. They moved the whole operation to California. A conglomerate bought it—MCA bought it—and they didn’t need me. But while at Decca I became vice-president of A&R, made pop records, jazz records, every kind of record in the world.

Can you think of any that would be of interest to guitar players?

Guitarists? I worked with all of them. Any studio guitarist of any note that was available, no matter what kind of session I had, I would always try and get who I felt was best for the job. I’ve forgotten a lot of their names. We used Mundell Lowe, Art Ryerson, Tony Mottola, Al Caiola. You’d have to refresh my memory. It’s ten years since I was at it. Blues guitarists, we used Jimmy Shirley, Teddy Bunn when he was alive, Everett Barksdale. Tiny Grimes with the Art Tatum Trio. All the jazz guitar guys. George Barnes was a favorite of mine. He’s such a great all-around guitar man.

How did recording change while you were at Decca?

Well, when tape came in it changed everything. And then the consoles changed and the amount of mikes you use and the separation. Balances changed. The isolation, when you’d have to isolate instruments. Then we started to work guitars and organs through the board in order not to have it leak in onto the mikes. Then you started to get all kinds of electronic reverberation and stuff like that. I did all the work in Nashville with Grady Martin and people like that.

When did overdubs start happening?

The first overdub that I know of was a [Sidney] Bechet session that Victor did. The first rock session with overdub was the “Rock Around the Clock” session I did with Bill Haley.

Do you think that the technological advancements that came into the studios were always a good thing?

I think it’s a good thing, yes, because you can do so much more and make cleaner records. The only thing is, when you get to jazz playing, I think it’s best when you can group everybody like when they’re playing in a room or on a job or on a stage—you know, a dance band, I’m talking about. Use the normal setup that they would have in order to hear each other properly and get the right relationship on their instruments in their own ears without having to put on earphones. When you work a club, you don’t wear earphones. And you get more feeling when you’re playing jazz, because the guy hears what you’re doing. He’s sitting next to you and he can put in a fill or give a kick on his bass drum and get you really going. He can ride it or play quiet behind you. He can do anything because it’s a complete unit.

And after a while when you rehearse and you get used to playing that way, if you get in the studio and you have to sit in a little cage or a singer has to go into an enclosed booth with a glass window on it and work with phones on, how the hell you gonna get a record to swing? It becomes mechanical. You might just as well do everything with a metronome, which some of them probably do.

I always liked what they call today “direct-to-disc recording.” It’s only a throwback to what I did in the ’30s and ’40s. ’Cause you had to get it in one take. There was no editing. You cut on a wax master or an acetate disc. If a guy blew a note or you didn’t like the feel you had, you had to take the disc off, put on another one, and start all over. You had to get it in one take. It had more feeling.

It sure says a lot about the musicians who recorded that way in the ’30s and ’40s.

Well, I think the guys that play today could do it if they had to. They would enjoy it. But now with the sweetening and the overdubbing and everything. You know, we would get in four terrific sides or three terrific sides on a slow day. It’s three hours, and we’d go out feeling satisfied. Today, the guy that plays the date, the sideman or whatever, doesn’t give a damn. It’s a job. He leaves, and the genius producer listens to it and he calls a couple of guys back. He adds this and he adds that or he puts in a synthesizer to fix something or to get an effect. And it’s a whole different ball game. Recordings are different. But if you’re talking of jazz, jazz is better going down the first time.

When was the first time you heard Bill Haley?

Oh, I heard him when he had the “Crazy Man, Crazy” record, which he recorded for another label.

How did Decca get him?

The fellow that published “Rock Around the Clock,” Jim Wise, brought him to me from Philadelphia. They brought him to me because they knew I made good records.

Before Bill Haley, who were you working with?

I did all the R&B records for the company. The biggest artists were Louis Jordan and Buddy Johnson & His Orchestra. There were a lot of singing groups and people like that. Then I did Lionel Hampton, Andy Kirk, Jimmie Lunceford. I think the greatest blues dance band in those years was the Buddy Johnson band—the one that did “Since I Fell For You” and “That’s the Stuff You Gotta Watch” and all those tunes. Of course, we had a good swing beat, although Buddy Johnson used a heavy backbeat. Hampton was starting to use a heavy backbeat. But when I did Jordan, we did a good swinging rhythm section with him. But the riffs that Jordan’s band used to play was that kind of riffing and stuff like we were doing on 52nd Street with pickup bands. I used to hum them to Bill Haley’s guys when we were working out riff backgrounds. But that wasn’t a reading band. Only one guy in the group could read music.

Bill Haley’s music must have been quite a change of pace when it first came out.

You mean for the consumer?

Yeah.

Oh, for white kids it was, yeah.

Did you see it as an extension of what black musicians were already doing?

Well, it was a combination of that, plus what the country and western guys were doing. It wasn’t rockabilly. It was something new. It was rock and roll, but it was a white kid trying to do what a lot of the blacks like Chuck Berry and Big Joe Turner were doing. But he got more of a backbeat and electronic sound than what the blues guys were doing.

How long did the “Rock Around the Clock” session take?

The most we could get in in three or four hours with Bill was two numbers because we had to put them together by rote. If a guy would goof, we had to go back to the top and start all over again. And then when we did the singing and the overdubs, we would be there all day to get a couple of numbers.

Was the guitar solo in “Rock Around the Clock” overdubbed?

No. That was original. I think Franny Beecher was the guitar player.

What was the effect at Decca when “Rock Around the Clock” became so popular?

Oh, they were very happy! The sales department flipped. We had a big artist. We all knew how exciting it was and what was happening out there in the street.

Was there a scramble to sign new rock and roll artists?

No. You could only handle one big act at a time in those years. That’s all the sales department would handle. We didn’t need to compete with our own act. There weren’t that many around that were that good that you could grab anyway. They started copying. We did get Buddy Holly & The Crickets, and we put them on the Coral label. But that was a little later. Haley was enough for me to worry about. I was with him for as long as he was at Decca—from around ’54 until he got in trouble with the tax department and he left.

Was he an easy guy to work with?

He was easy as an individual, but business-wise they got pretty impossible.

“Rock Around the Clock” is sometimes credited as being the first rock and roll hit….

That’s not true.

The first rock and roll record to make #1 in the charts?

Well, I don’t know how far [1953’s] “Crazy Man, Crazy” went. “Crazy Man, Crazy” wasn’t as good a record. It was the first big, giant record, but he had a couple in a row there, Bill did. Bill wasn’t knocked out of the box until Elvis Presley took it away from him. But they were making so much money, traveling all over and doing a couple of those films. They made so darn much money, they didn’t know how to handle it. They had very bad management. Bill Haley had very bad management.

As far as working with him as a producer goes, how much input did you have on Haley’s final product?

Oh, it was a combination. I think what I added was equal or even more than what they added. I just recognized what they were doing and put it all together for them. But they had a good idea. When they really got to learn it [laughs] and they took it down, it was it! It took them a while to learn their riffs and get their notes and all, but when it finally was all done you could get two or three great takes and choose which one you were going to use.

What happened to the takes that weren’t chosen?

They were probably wiped out. It was mono tape in those days. I don’t know what the engineers did with it.

Was there a steel guitarist in Haley’s band?

Yeah, that band had a steel guitar in it, like a Hawaiian guitar. Billy Williamson. He was one of the original guys. I used to use the steel for a percussive effect. I used to tell him to give me, like, lightning flashes, you know. I said, “Just hit the bar on the strings and get the percussive sound. And hit like brass.” I told him not to use it ordinary, when you slide it. I used to call it lightning flashes. He didn’t slide it and play it like a Hawaiian. Well, he might have sustained a chord.

He really came up with this effect, and I caught on to it right away and I made him do it intentionally. And then it became a really big thing with them. I said, “I want you to take that and make it explode! Give me a lightning flash, like lightning and thunder! Pow, pow!” And you’ll hear that on the records. It gives a terrific sound.

Did Haley have a full lineup when you met him, or did you bring in studio musicians?

Well, he used a studio drummer. I think it was Billy Gussak, but the rest of the guys came from Chester with him. They used to woodshed it in his basement. They’d try and get it together, and then they would come in to New York, and it would take us two sessions to do two tunes. Four to six hours. They were good players.

How was the guitar solo in “Rock Around the Clock” recorded?

I just put a microphone in front of his little amplifier and let him go!

How many tracks was that recorded with?

That’s a mono record. When we had to overdub, we had to get an extra machine and have the guys play in the studio, feed back the original tape into another machine. It was a mono tape. You couldn’t do more than one overdub because the thing gets brittle and ruins the quality too much. But it hardened it up a little bit. It gave it an extra something. I recorded them in a big ballroom.

A lot of the echo you hear on there, we had one little machine giving us electronic echo, but a lot of the room sound comes from that ballroom we played in. It was a dance hall, the Pythian Temple. That was one of the greatest recording rooms in the world for natural sound. It was an old dance floor. We used it for the natural echo for normal recordings and everything. It had a natural reverb in it, with the seats up above. It had a balcony. We hung big drapes from the balcony to kill some of the kicking around. It had a very high ceiling, beautiful wooden floor. I always set my men without flats to shield them from one another. So the guitar solo in “Rock Around the Clock” is direct-cut.

After Bill Haley, did you work with other rock and roll artists?

No. Well, I tried when the British stuff came in. You see, they took me out of that department completely, and they never even let me go to San Francisco when the San Francisco scene started. The last important thing…. See, I originally did the Weavers. The blues guitarist I recorded even before the Weavers was Josh White. When I did the Weavers and the folk scene came in, they went for two or three years tremendously. And then they had troubles and the country had troubles. Then when the San Francisco thing started it was like a folk revival when the Kingston Trio came in and the Gateway Singers and people like that.

I went up there on a trip to the coast and I got the Gateway Singers. We never made a hit single with them, but the Kingston Trio came in. I think they followed them into the Hungry I [nightclub], and they broke wide open. But when the rock band thing hit San Francisco, the company kept me in the East. At that point I was going to Nashville and doing Burl Ives and things like that. And when it happened in Britain, they took me out of that department. There was a whole political upheaval.

Where did you end up?

Well, I was still in the A&R department, but I was doing pop bands, shows—things like that. Reissuing what was in the catalog on 12-inch LPs. Going to Europe and doing Bert Kaempfert. I always had my bread winners, but they took me out of the rock scene.

It’s amazing that the rock and roll scene has lasted so long.

Well, it’s good, basic, happy music.

From your vantage point, Milt, what were the best days of jazz?

[Laughs.] You know, I can only talk for myself, and that’s when you’re out in the rooms every night and you’re going out drinking and enjoying it and running my jazz concerts. How could I say anything any different? It’s an obvious answer.

You’re right.

But there are guys that say the music that was played on 52nd Street in those years is the purest jazz ever played. It’s before it started to get wild. It was good all through the bop period. It wasn’t until you started getting into—what would you call it? Contemporary composition and electronic sounds. You know, how far away can you get from the basic roots of the music? It’s just like classical composition. You can have electronic music, you can have anything you want. It’s a free world. You’re a poet, you do what you do. But I like what I was raised with. For me, it’s got to be ebullient and basic. Billie Holiday and Bessie and Teddy—all the good players.

Who has the masters of the recordings you made?

The Commodores I have. Columbia is putting them out now, and Columbia’s Special Products revived the Commodore label. They’ve got about 18 LPs out now.

Has that been the major thrust of your work since 1971?

Yeah.

Have you ever written a book about your experiences?

No. I wanted to do one with Ralph Gleason, but my dear friend didn’t stay around that long.

When you look back on your career, what are you most proud of?

The jazz. The first 25 years of my musical career were jazz, and the second 25 was pop music plus some jazz. I got into seeing what the pop writers and lyricists were doing. I enjoyed competing with A&R men at other companies and seeing if they’d make a better record, catch the public’s fancy, and go to #1 or the Top 10. It got to be like a poker game or a bridge game—you trump their card or you try to beat them. It’s a contest. Very exciting.

Do you know how many hit records you’ve had?

In the days I had the big hits, there were no record industry association gold record awards, but I figure I made over 40 million-sellers. All by different artists. Computed to today, what originally might have been three million-sellers by Bill Haley in the continued sales through the years, Bill by this point may have five or six records that obtained a million. And Louis Jordan must have three or four, etcetera. You know, I did the Four Aces, the Mills Brothers, Ella Fitzgerald, Peggy Lee—her “Lover” record sold over a million records. Then you do a commercial thing like “Two For Tea Cha-Cha,” with Warren Covington fronting the Tommy Dorsey band. You have a million-seller when cha-cha came in. You gotta know what’s going on in the field. I did “Goodnight Irene,” “So Long (It’s Good to Know Yuh)” by the Weavers—they sold a million records each. “Hamp’s Boogie Woogie” sold a million records, “Flying Home” sold a million records. Those are by Lionel Hampton. I did the whole gamut.

What would you like to accomplish in the future?

[Laughs.] Enjoy my remaining years—that’s all! Make enough to pay my taxes and have bread on my table and keep the house painted and keep playing music. But to go out to the bars again and find another Billie—that’s not for me. No, I paid my dues. My son is in the television end of the business. He’s executive vice-president of ICM, in charge of television packaging. I got so burned up when MCA let me go and wouldn’t move me to California. He said, “Dad, you paid your dues. What are you gonna prove? They gotta catch up to you.” I says, “Yeah, but I got 20 good years of ideas and things I want to do.” So I went home and cleaned up my Commodore masters because the bootleggers were getting at them. I am happy to be doing that, and I would still like to do a record date or two. It’s a big thrill when I go and hear one of my old friends.

One last question. How did you ever come up with the name “Commodore”?

It’s a very simple answer if you know New York City. We were diagonally across from the Commodore Hotel. [Laughs.] That’s where the big bands played too, a lot of ’em. It was part of Grand Central. Actually, there’s no more Commodore Hotel. All you got left of those years is the Commodore label.

###

Coda: In 1993 Milt Gabler was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame by his nephew, actor/comedian Billy Crystal. In 2001, Milt, age 90, passed away in Manhattan, a photo of Billie Holiday at his bedside. Four years later, Billy Crystal produced the documentary and CD release The Milt Gabler Story.

###

For more on the early use of the electric guitar in jazz music:

The First Amplified Jazz Guitar Solos

Bennie Goodman Discusses Charlie Christian and Sings One of His Solo (audio)

Columbia Records Producer John Hammond Remembers Charlie Christian (audio)

Barney Kessel: The Complete “Charlie Christian” Interview (audio)

Finding Charlie Christian’s Gibson ES-250

###

Help Needed! To help me continue producing guitar-intensive interviews, articles, and podcasts, please become a paid subscriber ($5 a month, $40 a year) or hit that donate button. Paid subscribers have complete access to all of the 200+ articles and podcasts posted in Talking Guitar. Thank you for your much-appreciated support!

©2024 Jas Obrecht. All right reserved.

Thanks for this interview with a somewhat forgotten figure! "Jim Wise" is a phonetic spelling for Jim Myers, who not only published "Rock Around the Clock" but co-wrote it (as "Jimmy de Knight"). Also, the guitarist on the Bill Haley "Rock Around the Clock" session was not Franny Beecher, but Danny Cedrone, who died accidentally only two months later and never got to know what a classic it would become. Still, it's understandable that Gabler would remember Franny Beecher better, as he ended up staying with Haley for eight years after coming in as Cedrone's replacement.