The First Amplified Jazz Guitar Solos

How Eddie Durham, Leonard Ware, and Floyd Smith Set the Stage for Charlie Christian

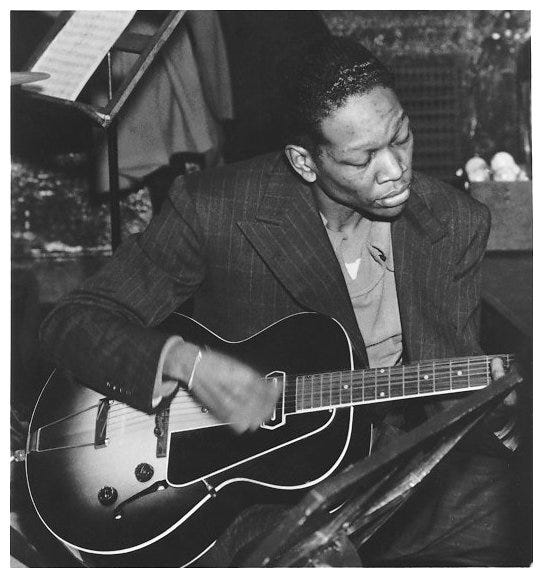

While honored today as the first influential electric guitarist in jazz, Charlie Christian was not the first to feature the instrument on a jazz record. During our 1981 interview, Columbia Records producer John Hammond remembered that two other jazz musicians were playing electric guitar before Christian: “One wa…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Talking Guitar ★ Jas Obrecht's Music Magazine to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.