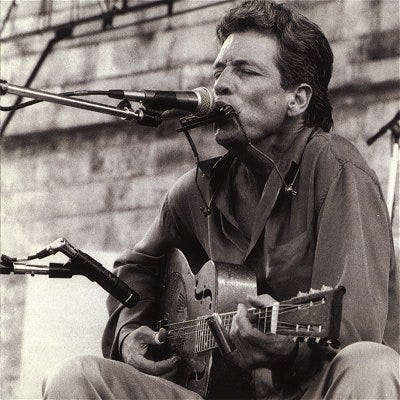

During my 1981 interview with Gregg Allman, I asked him to name his brother Duane’s best friend toward the end of his life. “John Hammond,” Gregg quickly replied. “He’s a beautiful man.” Duane Allman and John Hammond first met in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, in November 1969. John came there to record his Southern Fried album with the renowned Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section.

Earlier that year, Duane had scored his first major success as a studio musician, playing on Wilson Pickett’s “Hey Jude” with the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section. Duane’s band with Gregg, the Hour Glass, had just broken up, and Duane was now living in Muscle Shoals – a town so conservative that beer couldn’t be purchased anywhere – while Gregg remained behind in Los Angeles.

“I rented a cabin and lived alone on this lake,” Duane later said of his Muscle Shoals experience. “There were these big windows looking out over the water. I just sat and played to myself and got used to living without a bunch of that jive Hollywood crap in my head. It’s like I brought myself back to earth and came to life again through that, and the sessions with good R&B players.”

John Hammond had begun recording country blues music in 1962, and both musicians admired Robert Johnson and other early bluesmen. Allman was not originally scheduled to play on Hammond’s album, but he stopped by the studio one day to meet Hammond and ended up playing lead guitar on four tracks – “Cryin’ For My Baby,” “I’m Leavin’ You,” “You’ll Be Mine,” and “Shake for Me,” which was anthologized on 1972’s Duane Allman – An Anthology. They remained friends and jamming partners for the rest of Duane’s life. John has been credited with introducing Duane to the open-chord guitar tunings he eventually adapted for playing slide. I’ve done several interviews with John over the years. The one below – our first – took place on June 23, 1981.

###

I was wondering if you could tell me about Duane.

Sure! He was one of the premier lead guitar players – rock and roll, blues, any style. I mean, he was quite a terrific guitar player.

Do you recall the first time you met him?

The first time I met him was in Muscle Shoals, Alabama. I was down there to record with the band down there. It was being produced by Marlin Greene, and it had Barry Beckett, Roger Hawkins, Jimmy Johnson, David Hood, Eddie Hinton. And when I got down there, they thought that I was gonna be black, and I thought they were gonna be black. So they got pretty cold to me, you know. I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t know what to make of the scene. I was told that this was the band that recorded behind Aretha and all these people. So after about two days, we’d cut about four tunes or something. It was not going well.

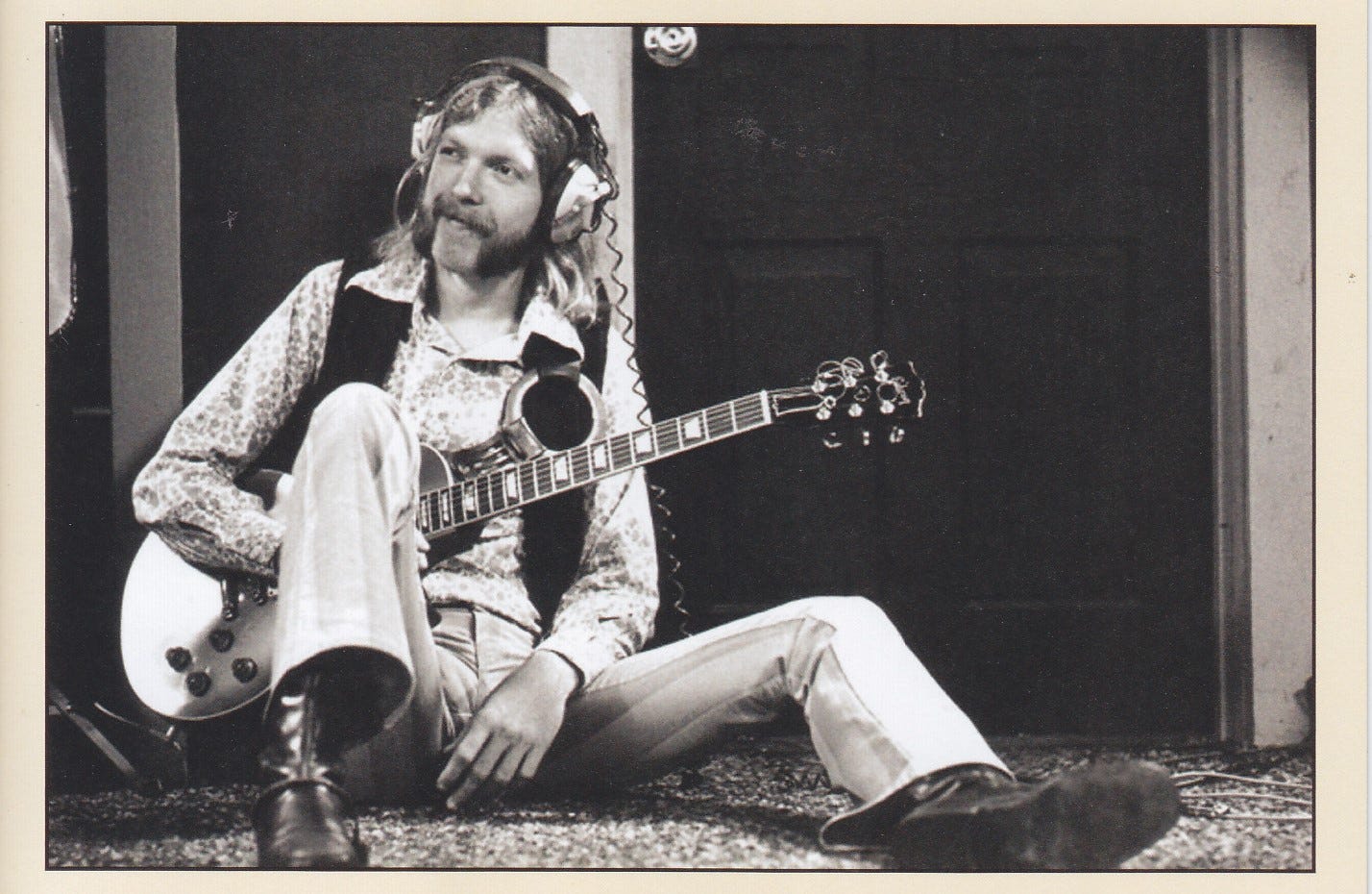

On the scene arrives this guy with long red hair down his back, eyebrows that crossed, and a moustache that went all the way into sideburns. He was wearing a T-shirt that said “City Slickers” on it. He arrived in this abandoned milk truck. And everybody said, “Hey, Duane! How ya doin’ man?” He said, “Where is this John Hammond guy? I wanna meet this guy! I really dig him.” They said, “You do?” And they all looked at me with new respect.

I was introduced to Duane, and Duane said, “Man, I sure dig your stuff! Boy, and I sure would love to play on your record if it’s okay.” I said, “Well, sure, I guess so.” I had never heard him play before, but these guys worshipped him. As soon as Duane gave me the okay, the session went fantastic. The album is Southern Fried.

This was in ’69. Not long after that, he put together the Allman Brothers Band. They had worked some jobs under the name the Allman Joys before that time. And then the next time I saw them they opened the show for me in St. Paul, in the winter. It was, like, 35 below zero, at the Union Labor Temple there. This was in late ’69, and it was very, very cold. We got together and we had a jam that night, and it was just terrific. It was the beginning of a long relationship I had with him. Duane got me together with the Paragon Agency, and I worked for them for about four years. I was on many shows with them. Duane was at my house the night before he died.

You’re kidding.

No. [Sadly] He was a good friend, and it was really sad, because he’d just gotten his health back, you know. He’d been up in the hospital – I think up in Buffalo. And just before he died he was in very good shape. And it was like an accident on a motorcycle. Really tragic. He was the real strength of that band. He was the absolute creative leader, you know. It took them a long time to get it back together when he died. He just had this energy. He just had all this dynamic energy to just explode all the time. There was a magnetism about him that made it special, you know.

Do you remember much about that last night you spent with him?

Sure. Yeah, we jammed all night. We played. He had a friend named Deering Howe, and I got a call – he was over at that house. I went over there. We had a few beers. And then it was time to leave, and he came over to my place. We played records and played some guitar together. We talked about recording another album together. I had to go to Newfoundland the next day, and he had to go down to Macon. He was in good shape – believe me.

Was this your house in East Hampton?

No, no, no. This was a loft I had on Broadway in New York. This was the night before he died. I forget the date, exactly, but that’s when it was.

When you used to jam with Duane, was it mainly on acoustic?

Acoustic – absolutely! He’d say, “Man, play this stuff here.” He’d ask me to play the Robert Johnson slide stuff. I mean, he was a fantastic slide player, but he played in a straight tuning [early on] – you know, not being tuned to an open chord. And so he used to watch me play in an open tuning. He told me he dug that. And I used to dig the way he played, very much.

Could you describe his style of playing slide?

Well, he [originally] played with it tuned straight – not to a chord. He just knew where to hit the notes with the slide so it would make the right sound. He played, like, single-string slide, and a few chord things.

Was he usually on?

I don’t think I ever heard him off. I said, “Man, how did you ever get to play that good?” He said, “By taking speed every night for three years and playing in little rock bands.” I said, “What?!” [Laughs.] I don’t know if he was kidding or not, you know, but the guy for sure was really a great guitar player. I mean, he had feeling. He really had sensitivity to all kinds of styles – blues and R&B stuff. He was just prolific.

Did he usually fingerpick when playing slide?

No. Not at all. He played with a flatpick, as I recall.

In the photos I’ve seen of the two of you jamming together, he’s playing an old metal-body National guitar.

Oh, right! He had one. That’s right. In fact, I think it belongs now to Dickey Betts. It’s been about four years or more since I was down in Macon and was around those guys, so a lot may have changed. I don’t know who has the old guitars anymore or anything. But there was a time when I was on a lot of gigs with them. I knew them all very well.

Is there anything you’d care to add, John?

Well, he was a unique guitar player. Not so much that there weren’t other guys who could play blues or R&B stuff, but his feeling and his magnetism were unique. And he was also a good friend – the kind of guy that everybody looked up to. He was a real leader. And what a tragic loss.

Do you have favorite cuts of his that you’d recommend people listen to?

The cuts with me, you mean? [Laughs.]

Yeah. Or other cuts.

Well, when he did “Shake For Me” on the album that we cut together, I was floored. There’s a lot more that was edited out of that. I mean, he played on and on and on and on. And it just had to be edited in order to fit the album. But like I say, he was the leader of the whole South thing – the Muscle Shoals sound, the Miami sound. He was the catalyst. He’s what made it fantastic. And everybody looked up to him. [At this point John began to cry.]

Thanks a million, John.

Oh, you’re quite welcome.

If you think of anything else, give me a call.

I certainly will. Take care.

###

Further reading:

John Hammond Talks Country Blues

Gregg Allman’s “My Brother Duane” Interview (Audio)

Dickey Betts: The 1981 “Duane Allman” Interview

Young Duane Allman: The Jim Shepley Interview

Young Duane Allman: The Pete Carr “Hour Glass” Interview

Young Duane Allman: The Bob Greenlee “House Rockers” Interview

Help Needed! To help me continue posting articles like this and producing podcasts of guitar-intensive interviews, please become a paid subscriber ($5 a month, $40 a year) or hit that donate button. Paid subscribers have complete access to all of the 150+ articles and podcasts posted in Talking Guitar. Thank you for your much-appreciated support!

©2024 Jas Obrecht. All right reserved.

Love this whole series! As slide players go Elvin to me is the equal of any of his peers on slide! As opening act he set a VERY high bar. And that “Joy to the world but comes from Elvin when he was with Butterfield…at the end of “East/West”!