The 1990 King Biscuit Blues Festival in Helena, Arkansas, spotlighted an impressive lineup, with Albert King and James Cotton fronting powerful bands and Johnny Shines appearing with Robert Lockwood, Jr. One of the highlights came midday when John Hammond took to the stage alone. A harmonica rack around his neck, he sat cradling a beat-up National. His opening slide into a familiar Robert Johnson riff brought a thunderous roar of appreciation from the sun-drenched crowd. Hammond kept fans on their feet throughout his set, conjuring potent images of Johnson, Son House, Blind Willie McTell, and other country blues greats of generations past. It’s a scene John’s lived over and over throughout a distinguished career that has brought him in touch with virtually every major bluesman who survived into the 1960s.

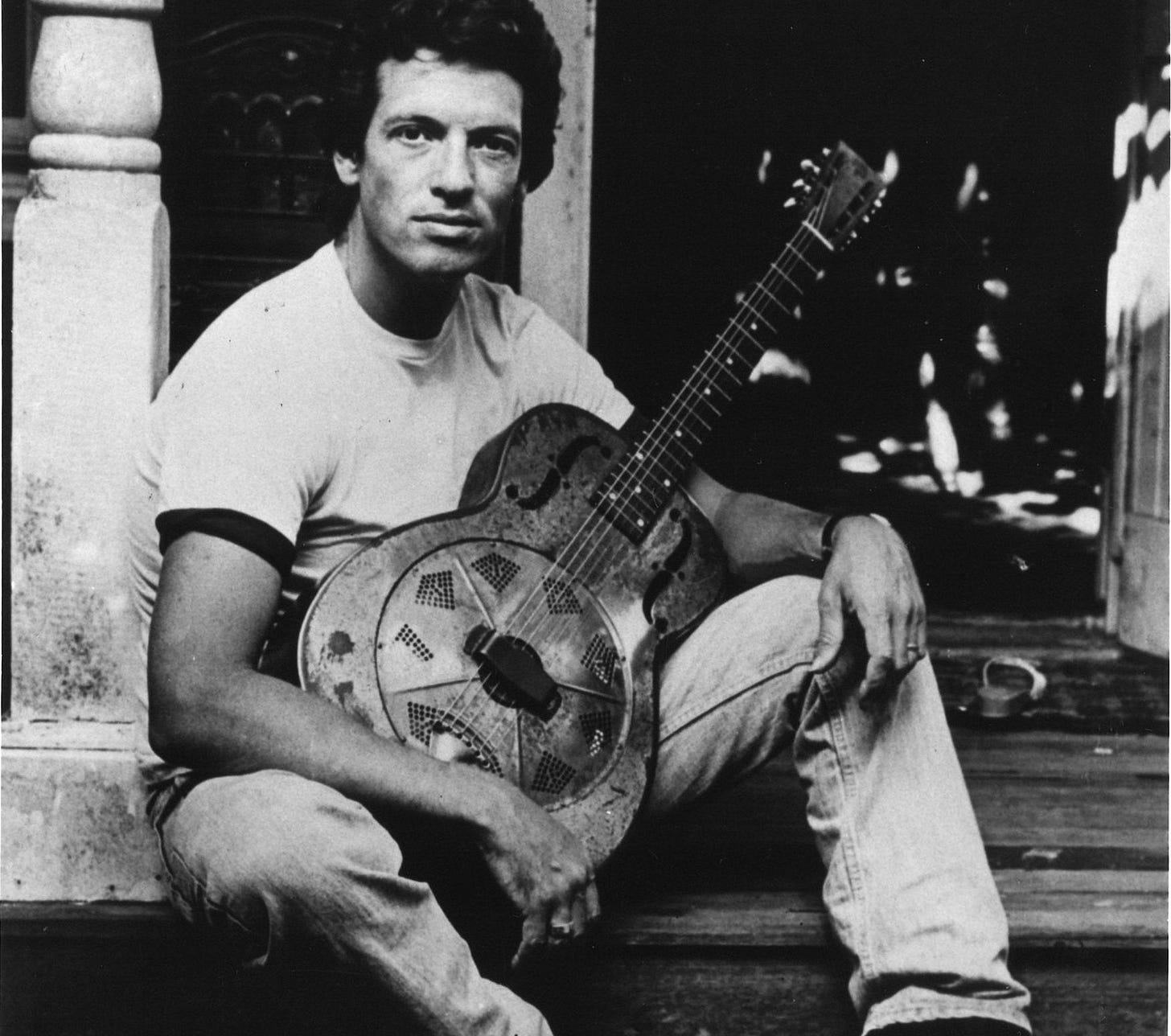

The son and namesake of the famed Columbia record producer, John discovered early on that the blues provided the perfect antidote for teen angst. By 1960 he had acquired his first acoustic guitar. He quickly taught himself to play, and soon afterwards released his debut album. While Hammond has made a few forays into electric blues and rock bands, solo acoustic blues remains the heart of his art. The following conversation took place in Berkeley, California, on July 25, 1990.

You still seem inspired by your original vision.

Yeah, it hasn’t gone away. There are times when I feel closer to what I started out to do than even when I was just beginning. I feel a lot more confidence on the stage than I used to. When I began, I had all that energy without a lot of experience.

Did you know many of the old-time musicians?

I worked on shows with Furry Lewis, John Hurt, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Mance Lipscomb, Fred McDowell, Bukka White, and Arthur Crudup. I played with Son House and Skip James at the Gaslight in New York! Dick Waterman brought Son on a tour of the coffee-house circuit, and he had just recorded an album for Columbia in ’63 or so. When I was introduced to Skip James, he was very shy. He was sick and very uptight about it. He had cancer and was really quiet, but what a fantastic voice! What a great vision, and he was so unique.

Victoria Spivey was already in her sixties when she started to come around to hear me play at Gerde’s Folk City in New York. She would take me home to her place in Brooklyn. I made some recordings for her, and she introduced me to Roosevelt Sykes, Babe Stovall, and Lonnie Johnson – I was on some gigs with him at Gerde’s! Lonnie wasn’t playing blues anymore. He had been found as an elevator operator in a hotel in Philadelphia, so he sang some sort of sweet gospel-type tunes and jazz standards. He’d lost that edge, but every now and then there’d be moments and flashes. He was such a nice man, a beautiful guy. His early recordings are staggering – the sides where he accompanies Texas Alexander in the late ’20s. He played any style. He played with Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong. He was just phenomenal. He played 12-string guitar at some points in his early career, and when I saw him he was playing with a flatpick. I met the Reverend Robert Wilkins briefly, but I didn’t get to hang out with him.

Probably my biggest influence when I first started to play was Big Joe Williams. I was on some shows playing harmonica behind him because he liked me; this was 1962 around Chicago. Big Joe played that 9-string guitar and had a little suitcase amplifier, and it was outrageous. He was so good, so intense! I used to watch him play with my jaw slack. I was profoundly influenced by Big Joe. Like Robert Johnson, he used an open-A tuning or open-G with a capo. Even though I only knew him from hanging out with him for about a week, it was enough to be severely impressed. He was so intense!

Big Joe was a character, man. He carried a gun that was so big, an Army .45, and he wasn’t a tall guy, but he was big. I drove him around for a week, and we went to Sylvio’s one night. Somebody insulted Joe and he pulled out this gun, and I didn’t even know he had a gun. All of a sudden I was more scared of Joe than anything else! But he was cool. He drank schnapps and whiskey and everything all night; it was amazing how much he could consume.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Talking Guitar ★ Jas Obrecht's Music Magazine to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.