By the time my junior year rolled around at John Carroll University, I was devoted to music. My LP collection filled two orange crates, and my room in Dolan Hall was a gathering place for stoners and music aficionados. After sneaking off to a quiet place to share a joint, we’d spend hours jamming on acoustic guitars or spinning LPs on my portable stereo with satellite speakers. In those days, the Allman Brothers, Joe Walsh, CSN&Y, Richie Havens, John Mayall, Johnny Winter, Humble Pie, The Who, and Derek & The Dominos were in heavy rotation. It was early 1973, and life was good.

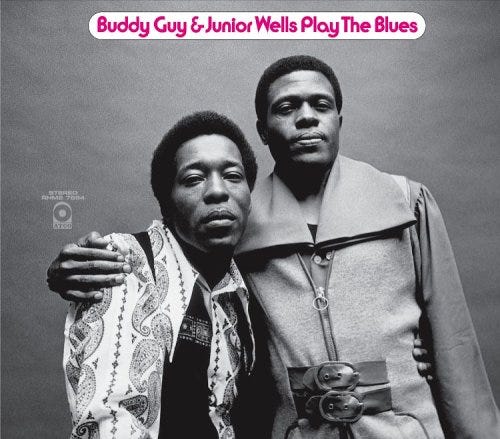

My love for blues music was already in full swing, but albums by the original Black artists were hard to come by. At a store in nearby Coventry Village, just outside of Cleveland, I chanced upon a new major-label release called Buddy Guy & Junior Wells Play The Blues. The B&W cover shot of Junior and Buddy with their intense expressions and batwing collars sold me on the album before I heard a single note. To me, this image screamed This is the real deal!

I carried the LP back to the dorm and gave it a spin. My guitar-playing pals were thrilled that Eric Clapton made a guest appearance playing slide, but to me it was all about Buddy’s staccato soloing and Junior’s harp wizardry and one-of-a-kind voice. A half-century later, Junior’s original “Come On in This House/Have Mercy Baby” still pulls me in every time.

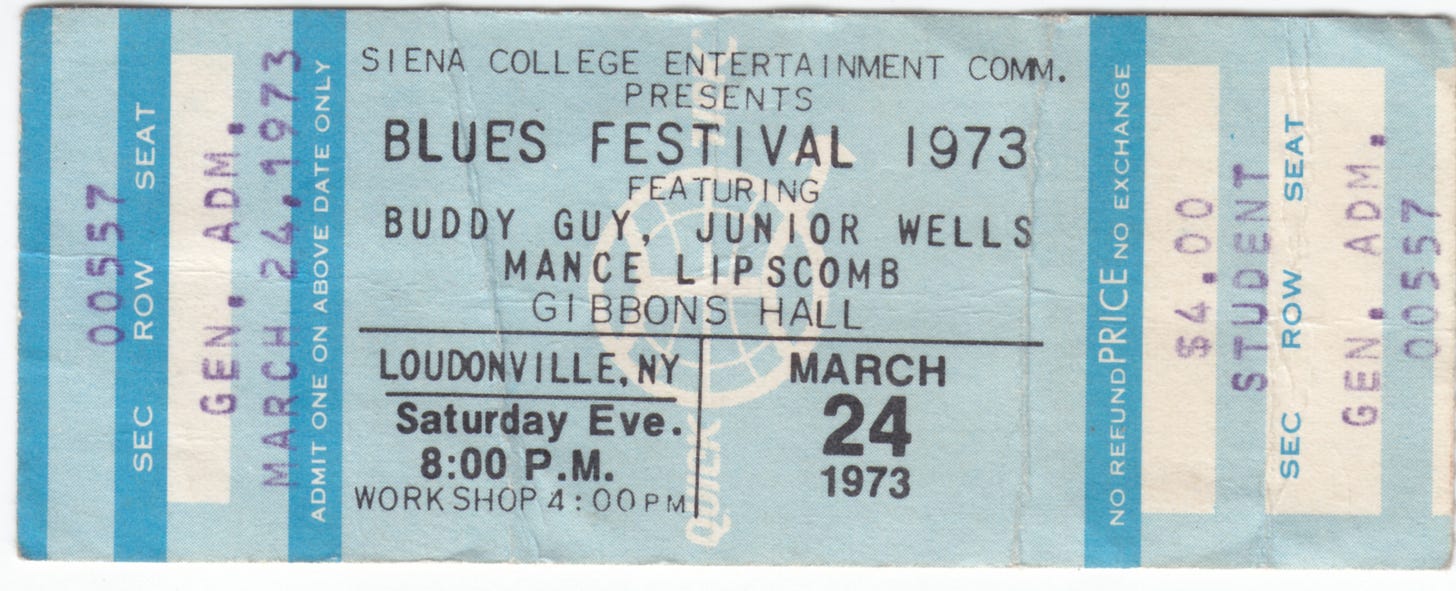

Somehow word reached us that Buddy and Junior were booked to appear that March at the Siena Blues Festival in upstate New York. In those days hitchhiking or, less frequently, ridesharing were my usual methods of transportation. The 470-mile distance from Cleveland to Loudenville, New York, seemed daunting, but I was determined to go. Luckily, four of my friends—Jimmy Aubrey, Patty Owens, and sisters Ginny and Lizzie Anson—were up for a road trip, and one of them had access to a car. Praise God!

At that time, there was a marijuana drought on our campus. Just before we departed, I managed to bum enough to roll a single joint, using a yellow Zig-Zag Wheat Straw paper.

During the drive, we played Eric Clapton at His Best on a battery-powered portable cassette player. We arrived at Siena College just in time to score tickets for the evening concert. The only seats we could find were all the way at the back of Gibbons Hall.

The warm-up act, it turned out, was none other than the great Texas songster Mance Lipscomb. Performing alone with an acoustic guitar, he played a wonderful repertoire of blues and pre-blues songs that he’d learned while growing up and sharecropping around rural Brazos County. Set to a propulsive, throbbing bass note, his mesmerizing pocketknife-slide renditions of “Jack O’ Diamonds” and “The Titanic” were worlds away from any music I’d ever heard before. The rest of the audience seemed just as spellbound as I was. (Years later, I realized that these were essentially respectful covers of Blind Willie Johnson songs.)

After intermission, the house lights dimmed again and Buddy and Junior’s backup band came onstage and played a couple of instrumentals. When they announced Buddy Guy, I nudged Jimmy and said, “Follow me.” I boldly led him through the crowd and, acting as if we belonged there, we stepped into the area reserved for photographers. No one questioned us. Buddy’s toes were just a few feet from our faces as he fronted two or three songs. Finally Junior Wells came onstage and began, as I recall, with “My Baby She Left Me (She Left Me a Mule to Ride),” drawing thunderous applause. I was in blues heaven!

Midway into his next song, I pulled out my joint—in those days, mind you, possession was a serious offence—and sparked it up.

Junior saw what I was doing, came right over, and plucked the joint from my hand. Standing tall, he turned his profile to the spotlight, put the joint to his lips, and did the mightiest inhale I’ve ever seen. By the time he’d finished, more than half the joint was gone. He exhaled a huge cloud of smoke, to rapturous applause, and handed me back the roach.

At that moment, two thoughts simultaneously ran through my mind: an ecstatic “Wow!” and a woeful “Hey, man, that was my last joint.”

The rest of the show was inspiring. Oddly enough, though, the best was yet to come.

After the final encore, Jimmy and I stuck around until most of the fans had filed out. Walking around to the back of the venue, we spotted Mance Lipscomb sitting by himself on the edge of a loading dock, playing his guitar. As we cautiously approached, he welcomed us with a smile and continued to play. Two or three other lucky concert-goers joined us.

For the next half-hour or so, Mance treated us to an impromptu performance of stories and songs. I vividly remember the sounds his pocketknife made as it clattered against his frets and that the whites of his eyes seemed yellow under the streetlight. When someone came out to tell him it was time to go, he put down his guitar and warmly shook our hands.

That great JCU reefer drought and Junior Wells bogarting my only joint turned out to be a blessing in disguise. On the drive home, we were pulled over by two uniformed representatives of New York State Police, likely on the lookout for long-haired hippies with out-of-state plates. They searched our luggage and even combed the floormats for seeds, to no avail. We made it home with smiles on our faces.

###

For more on Mance Lipscomb, check out “Mance Lipscomb: Texas Sharecropper and Songster.”

###

To help me continue producing articles like this and podcasts of guitar-intensive interviews, please become a paid subscriber ($5 a month, $40 a year) or hit that donate button. Paid subscribers have complete access to all of the 130+ articles and podcasts posted in Talking Guitar. Thanks for your much-appreciated support!

©2024 Jas Obrecht. All right reserved.