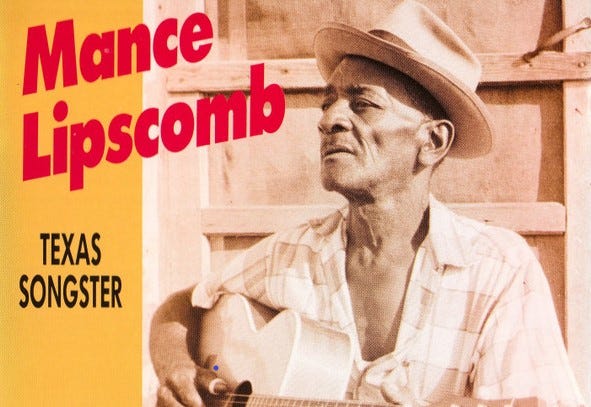

Mance Lipscomb: Texas Sharecropper and Songster

A Classic Blues Album Recorded in a Single Evening

During Mance Lipscomb’s youth, the nearest town, Navasota, Texas, retained the trappings of the “Wild West.” Its streets were overrun with violence and crime. Historian Robert Caro wrote that in 1908, when Mance was 13, “Shootouts on the main street were so frequent that in two years at least a hundred men had died.”

At that time, Navasota had a population of around 3100 citizens. Old timers there still recalled the horrors of slavery and the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in the years following Emancipation. Blacks were being lynched. After murdering Populist leaders in the Black community, oath-bound members of the secretive White Man’s Union took over elections. Little wonder that young Mance took solace in music, teaching himself to play ballads, jigs and reels, breakdowns, pop songs, waltzes, rags, blues, spiritual hymns, and circus tunes. In time, his repertoire came to include about 350 songs, many of which pre-dated blues music.

Lipscomb was born in Brazos County on April 9, 1895. Several variations of his given first and middle names, phonetically pronounced “Bowdie Glen,” show up in public records. In the 1900 census, when he lived near Millican, he was listed as “Body G. Lipscomb.” In 1910, he was identified as “Bodie Lipscomb.” By then his family and acquaintances were calling him Mance, short for “emancipation.”

Mance’s father, Charlie Lipscomb, was a former slave. His mother, Janie Pratt, was half Black and half Native American. His father, Mance explained to Paul Oliver, was a professional fiddler: “He played way back in olden days. You know, he played at breakdowns, waltzes, schottisches, and all like that, and music just come from him to me. That’s where I learnt it from. Papa was playing for dances out, for white folks and colored. He played ‘Missouri Waltz,’ ‘Casey Jones’ – just about anything you name, he played it like I’m playin’. He was just a self-taught player until I was big enough to play behind him, then we two played together. Then when I got to size, he took me around to play with him.”

Mance remembered that his mother “used to sing all the time. We’d be working the cotton fields together, and she’d be singing.” His mother bought him his first guitar, paying an out-of-luck gambler $1.50 for the instrument. Mance became a facile bare-finger player and for slide used a pocketknife held between his thumb and index finger. Singing with a warm, guileless voice, he set many of his songs to an alternating bass pattern. “‘Sugar Babe’ was the first piece I learned, when I was a little boy about thirteen years old,” Mance remembered in Paul Oliver’s Conversations with the Blues. “Reason I know it so good, I got a whippin’ about it. Come out of the cotton patch to get some water, and I was up at the house playin’ the guitar, and my mother come in. Whopped me ’cause I didn’t come back – I was playin’ the guitar:

Sugar babe, I’m tired of you

Ain’t your honey, but the way you do,

Sugar babe, it’s all over now

All I want my babe to do,

Make five dollars and give me two

Sugar babe, oh sugar babe, it’s all over now…

Other than playing with his father, Mance told Oliver, he did not learn from anyone else: “I started out by myself, just heard it and learned it. Ear music. And nobody didn’t learn me nothin’. Just pick it up by myself. I didn’t know any notes, just play by ear.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Talking Guitar ★ Jas Obrecht's Music Magazine to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.