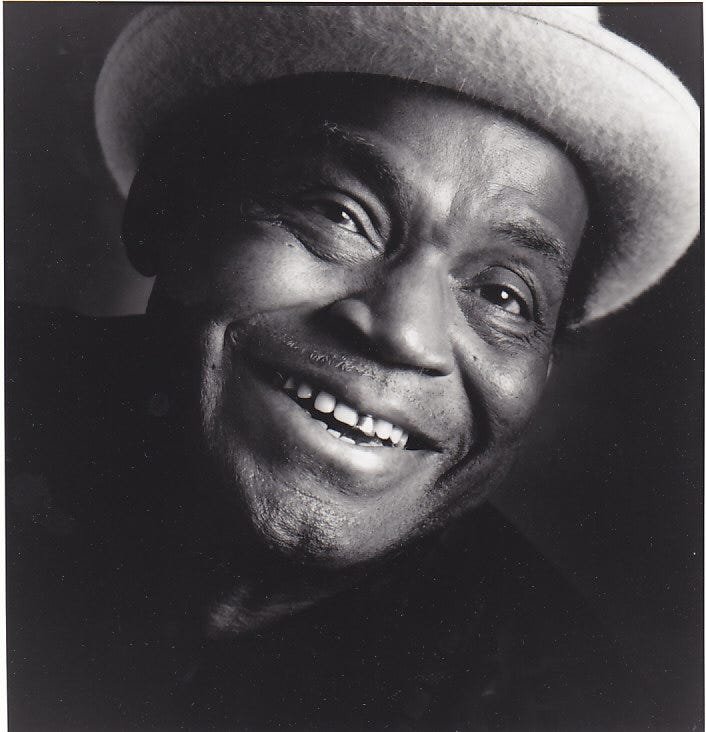

Willie Dixon on Songwriting, Bass Playing, and the Blues

My 1981 Conversation with the Poet Laureate of the Blues

For four decades, Willie Dixon loomed at the forefront of Chicago blues, working as a bassist, arranger, band leader, producer, talent scout, agent, A&R man, and music publisher. His most enduring contributions, though, were the songs he wrote. Dixon made Muddy Waters the “Hoochie Coochie Man,” taught Howlin’ Wolf “Evil” and “Spoonful,” and showed Sonny Boy Williamson how to “Bring It on Home.” “Willie Dixon is the man who changed the style of the blues in Chicago,” said Johnny Shines, a regular on the scene. “As a songwriter and producer, that man is a genius. Yes, sir. You want a hit song, go to Willie Dixon. Play it like he say play it, and sing it like he say sing it, and you damn near got a hit.”

Laced with images drawn from his Mississippi childhood and subsequent life in Chicago, Dixon’s lyrics explored longing, lust, love, betrayal, endurance, joy, and other real-life experiences. Some of his best bordered on poetry. Consider, for instance, these verses from “Wang Dang Doodle”:

Tell Automatic Slim, tell Razor-Totin’ Jim

Tell Butcher-Knife-Totin’ Annie, tell Fast-Talkin’ Fanny

We gonna pitch a ball, down to that union hall

We gonna romp and tromp till midnight

We gonna fuss and fight till daylight

We gonna pitch a wang dang doodle all night long

All night long, all night long, all night long, all night long

We gonna pitch a wang dang doodle all night long

Tell Fats and Washboard Sam that everybody gonna jam

Tell Shaky and Boxcar Joe we got sawdust on the floor

Tell Peg and Caroline Dye we gonna have a heck of a time

And when the fish scent fill the air

There’ll be snuff juice everywhere

We gonna pitch a wang dang doodle, all night long

All night long, all night long, all night long, all night long

For Dixon, writing lyrics was inextricably linked to reporting on the human condition — “the facts of life,” as he described it. To this day, many consider him the poet laureate of the blues.

Born William James Dixon in Vicksburg, Mississippi, on July 1, 1915, Willie learned to communicate in rhymes with his mother, a religious poet. He had vivid recollections of skipping school to follow around Little Brother Montgomery’s band as it played atop a flatbed truck. In his teens he served time in Mississippi prison farms. He began his musical career singing bass parts for the Union Jubilee Singers gospel quartet. In 1936 he left Mississippi for Chicago and devoted himself to boxing, reportedly winning the Illinois State Golden Gloves Heavyweight Championship the following year. His subsequent professional career lasted four bouts (or five, if you count the fracas with his manager in the Boxing Commissioner’s office). Guitarist Leonard “Baby Doo” Caston talked Willie into making music his career and built him his first bass out of a large tin can. In 1939 they formed the Five Breezes, which specialized in jazzy vocal harmonies. The band performed until at the outset of World War II, when Dixon was jailed for refusing induction into the armed forces. After a year of legal entanglements, Willie was free to gig around Chicago with his new lineup, the Four Jumps of Jive.

After the war Dixon and Caston formed the Big Three Trio, which recorded for Columbia. They were big fans of the Mills Brothers, and their harmony vocals hit a popular note with white audiences along the North Shore. After hours, Dixon headed to Chicago’s South Side to jam with Muddy Waters and other bluesmen. Hearing Dixon at the El Casino Club, the Chess brothers recruited him for their Aristocrat label, the forerunner of Chess Records. Dixon’s initial contribution was as a studio musician. By 1951, he had full-scale involvement with Chess Records and its subsidiary, Checker. As the company’s staff producer and chief talent scout, Dixon had a hand in the success of Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Little Walter, Jimmy Rogers, Sonny Boy Williamson, Koko Taylor, and many others. In 1955 he began recording singles under his own name, for Checker, but these did not fare as well as other performer’s versions of his songs. While at Chess, Dixon played bass on the breakthrough rock and roll recordings of Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley. Later in the 1950s, he plied his skills at Cobra Records, helping Otis Rush, Magic Sam, Buddy Guy, and Betty Everett get their starts.

During the early 1960s, Dixon helped organize the American Folk Blues Festival and went on their tours of Great Britain and Europe. Audiences, who recognized his name via songwriting credits on the back covers of albums, flocked to see him in person. “I can’t say enough about Willie Dixon,” said Keith Richards. “I mean, what a songwriter! To me, that’s one of the names. When I was getting into the blues, it was, ‘Who wrote this?’ I was looking at Muddy Waters records, and who wrote it? ‘Dixon, Dixon, Dixon.’ The bass player is writing these songs? And then I’m lookin’ at Howlin’ Wolf: ‘Dixon, Dixon, Dixon.’ I said, ‘Oh, yeah, this guy is more than just a great bass player!’ And let’s face it: He was an incredible bass player. You know, that would be enough. But he’s the backbone of post-war blues writing, the absolute. Personally, I talk of him and Muddy in the same breath, and John Lee [Hooker], come to that. You know, gents. These guys don’t have to prove anything. They know who they are. They knew what they could do. They know they can deliver. Willie, to me, is a total gent and one of the best songwriters I can think of. Willie Dixon is superior.”

Early on, the Rolling Stones established their blues credentials with Dixon’s “I Just Want to Make Love to You” and scored a 1964 Top-20 hit in the U.K. with their slide-driven reading of his “Little Red Rooster.” While making a name for himself in London, Jimi Hendrix thrilled BBC listeners with his otherworldly cover of “Hoochie Coochie Man.” Cream, with Eric Clapton on guitar, transformed “Spoonful” into a classic power trio jam. Clapton’s peers, Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page, each covered two Willie Dixon songs on their first post-Yardbirds albums, Beck and Rod Stewart doing “You Shook Me” and “I Ain’t Superstitious” on Truth, and Page featuring “You Shook Me” and “I Can’t Quit You Baby” on the first Led Zeppelin album. Back home in the U.S., Dixon’s songs easily crossed over into rock, with noteworthy covers by the Doors, Allman Brothers Band, Grateful Dead, Bob Dylan, and many others. He’s doubtlessly the only composer in history to have his songs covered by Styx, Queen, Oingo Boingo, PJ Harvey, and Megadeth.

Willie Dixon released several solo albums, notably 1970’s I Am the Blues, on Columbia, and the 1989 Grammy-winning Hidden Charms. In the late 1980s, Chess Records celebrated his career with the Willie Dixon box set. Near the end of his life, Dixon collaborated with Don Snowden on an autobiography, I Am the Blues: The Willie Dixon Story, and founded the Blues Heaven Foundation. Willie Dixon died of heart failure on January 29, 1992, and was buried in Burr Oak Cemetery in Alsip, Illinois.

Over the years, I spoke with Willie several times. He was always helpful, friendly, and insightful. My favorite interview with him, published here in its entirety, took place on April 21, 1980.

Are you playing much bass these days?

Yes. I was playing last night at the Wise Fool here in Chicago, and last week I was over in Ohio. And the week before that, I was up in Rhode Island, New York, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia.

What kind of bass are you using?

Oh, I’m using a upright bass. It’s a old Kay. My son, he play bass. He’s got one of those from England – I done forgot the name of it, but it’s one of those that’s made in England. He’s had it a good while. And I play the upright Kay bass.

How long have you been playing the one you have now?

Oh, this Kay bass I have, I had it ’round ’bout 18 years or something like that.

Do you ever play electric bass?

Oh, yes! A long time ago, I first started on the electric bass, when they first came out with them, you know. But at that particular time they wasn’t doin’ very much rock-style stuff. I found out that the old upright bass gave the type of things that I was doin’, like the blues and the spiritual things, a better background sound. Of course, the modern bass do a beautiful job on the modern-type songs, you know, but I had one at first. Jack Myers – you know, the fellow that was playin’ with Buddy Guy – I let him have it.

How many basses have you owned during your career?

Oh, I would say I’ve really owned about five different basses. I bought a Fender bass for my son once. And then I had one given to me once. I’ve owned five basses.

When you started performing in the late 1930s, who were the bass players that you listened to?

Well, I used to listen to this fellow who used to play with Duke [Ellington] a long time ago, Blanton. Blanton was my idol. Jimmy Blanton.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Talking Guitar ★ Jas Obrecht's Music Magazine to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.