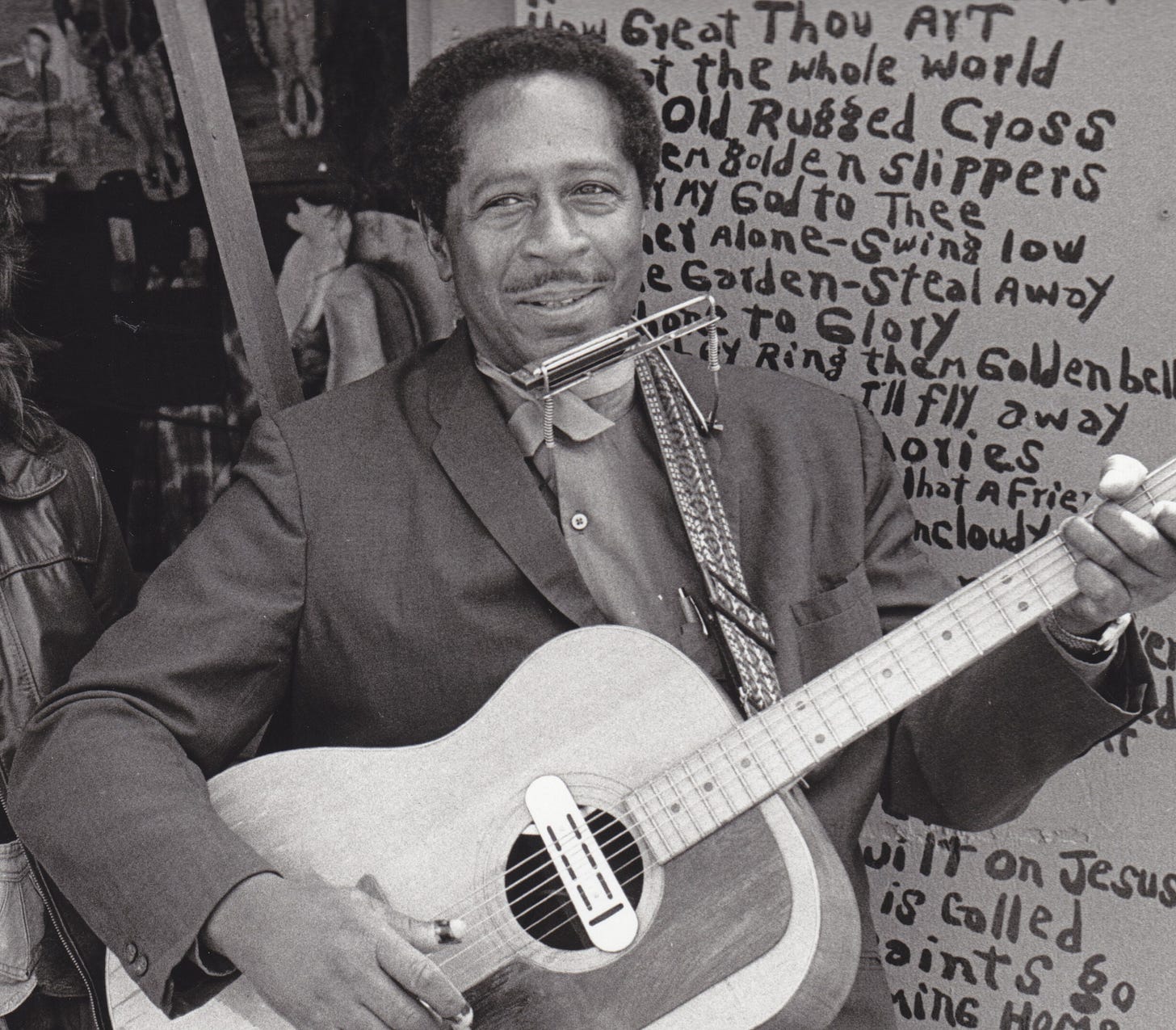

On a Saturday morning in March 1982, I was scouring the flea market in San Jose, California, looking for old guitars. Suddenly I heard loudly amplified music I never imagined echoing in such a place. Even from several aisles over, the songs sounded straight off of an antebellum cotton plantation or, at the latest, a turn-of-the-century minstrel show. I made my way over to a homemade shack built atop a flatbed trailer attached to motor home. Its walls were plastered with hand-lettered signs – “America’s Oldest Music,” “Donations Accepted – I Make No Salary,” and lists of song titles.

Inside sat 72-year-old Abner Jay, blowing harmonica, fingerpicking an oversize acoustic guitar, and singing Deep South music. Some of his repertoire predated blues and jazz by decades. His left foot kept time on a cymbal while his right foot beat a drum. A Mexican-American family stopped to listen. The coins the father handed to his small children soon clanged in Abner’s donation box. Moments later a woman shoved a crumpled bill down the slot.

I approached him during his break and asked if he’d be interested in doing an interview. “I don’t do no talkin’ on Saturdays or Sundays,” Abner drawled at me through his microphone. “Them’s my workin’ days. If you want to interview me, come ’round during the week, when I got nothin’ but time. I’m easy to find – the only trailer parked behind the Chevron station at Berryessa and Capitol Avenues. Be there all week.” He turned away, grabbed an antique 6-string banjo, and began singing and picking a delicate version of “Oh, Susannah.”

Two days later, on March 30, 1982, Abner pointed me toward a seat in his motor home. While I set up my tape recorder, he stuffed a whole raw chicken into a two-quart pan, without any water or grease, pushed on the lid, and turned the stovetop burner on low. Then he sat across the table from me and began a no-holds-barred conversation that lasted seven hours. Midway through, Jon Sievert stopped by to take some photos.

Abner Jay turned out to be one of the most remarkable, memorable, and outspoken musicians I’ve encountered. He projected an indomitable spirit and displayed wide-ranging knowledge of the evolution of Black music going back to before the Civil War. Here’s the first part of that epic conversation.

***

How long have you been doing this type of work?

Since 1928.

Have you been a musician most of this time?

All the time.

Where were you born?

Ocilla, Georgia. I been in all walks of this music business. Started out with a medicine show. There ain’t nobody livin’ or dead been in music consecutive as long as I have and nothin’ big ever happen. That’s right. Try to think of somebody. Nobody. People talk about payin’ dues. I’m steady out here every week – somewhere – and I make a living. Always have made a livin’. Raised 16 kids doing this. I’ve only been in flea markets now about two and a half years. Played nightclubs, Holiday Inns, Ramada Inns – you name it, man. I been comin’ to California since ’45. Come to San Jose. I played right here in 1951, right here in San Jose.

What year were you born?

1910.

Were there a lot of kids in your family?

13.

Were any of your brothers and sister musicians?

Nn-nn [shakes head]. I wouldn’t advise a dog to be a musician.

Were any of your relatives musicians?

Yeah. Lot of cousins. I had one first cousin made it real big. He was blind. He got his eyesight when he was 53, and soon after that he died. I can’t think of his damn name – I never did meet him. My daddy’s sister’s boy. He was some hell of an organist.

Were your parents musicians?

Well, my daddy was. He was a guitar player and the best harmonica player I ever heard to date. And he turned country preacher way back here in 1931, I believe it was. And he quit doin’ it and just read the Bible all the time and preached. Well, you see, way back there, that’s why Black people is the father of all this soul music. It goes way back into slavery – in bondage, they would call it. They didn’t have nowhere to go. You’d be surprised what you do if you shut in. Like the man who invented the Winchester rifle was in solitary confinement. [Here Abner refers to Carbine Williams, who as a convict in the 1920s invented the operating principle of Winchester’s M1 carbine.] You’d be surprised what I do shut in in this thing [points to his portable shack]. And they made the banjo, and you’d be surprised at all the songs Black folks made up. Did you know that a Black man is the father of bluegrass?

No, I didn’t.

Well, these guys that been to school for this stuff – all these folklore people. They know, but they don’t broadcast it. I talked to Chet Atkins like I’m talkin’ to you. You know where Chet Atkins got this inspiration from in his style? Blind Guitar Blake. I heard him tell it on nationwide television many times. I know the story backwards.

On Saturday I was talkin’ to two Black couples, and this girl blew my mind – 22 years old, and she could hold me a conversation about old Black musicians. It was very unbelievable. And I said, “How do you know all this?” Her daddy is a jazz guitarist. And she could hold me a conversation all day. We talked. Her husband just stand there – he don’t know his asshole from a hole in the ground. He don’t know nothin’. Boy, that kid was so sharp, man! She says, “Yeah, most of these Blacks, all they know about is B.B. King and Ray Charles and James Brown.” And man, she was goin’ way back – Bessie Smith! Way on back there. I said, “I don’t know how you know this. Are you sure you didn’t study folklore?” She said, “No.”

And she stood there eyeballin’ me, so I thought she was one of my daughters. I got 16 kids – I got eight girls, but I don’t know where they are. They all grown, except one. And that couple stayed there all day, off and on. And that’s very unusual. I said to her, “Wasn’t no such thing as a white harmonicist. Now they all white. They the one makin’ the money – Paul Butterfield.” I listen to all kind of music all the time. I got all kind of tape. I can tell a white dude from a Black one the second I hear ’em.

Junior Wells is a good harmonica player.

He the only new one. He’s the youngest one out there. But man, you can go back to Little Walter – you remember Little Walter? He made it big with just blowin’ the damn harp.

Now the Black generation, boy – and I told them people Saturday – if I had a pile of money, I’d like to get all of them in a big stadium and bullwhip the hell out of ’em. I mean that too, man. [Raises voice] The greatest thing God gave them, they don’t have no respect for their own. They want to be managers, clerks. I’ll tell you, boy, I been Black 72 years, and they ain’t shit! They tryin’ to lose their fuckin’ identity! You understand? That’s why 45% of your Black teenagers are unemployed. 16% of Black adults are unemployed. And you want to go to a store – excuse me, I don’t know how to talk but plain – if you want to go in a chicken-shit, run-down, Longs drugstore or Safeway, and they got a Black manager, he say [imitates a nervous-sounding man], “Oh, we out of alcohol.” You say, “You got aspirins?” “Oh, we out of aspirins.” Now, I’m talkin’ from coast to coast. You go in a grocery store. “Oh, we out of flour.” “Y’all ain’t got no tomatoes?” “We out of tomatoes. Truck be in tomorrow.” Make a survey.

Now, I listen to National Public Radio two hours every day – All Things Considered. And they got people that go out and interview. I been on there many times. People like me – unusual things – and they say it like it is. You ought to listen sometime. National Public Radio. And they used to have old Black musicians on there. But how many people listen to National Public Radio? I don’t know, but there ought to be a law that everybody should listen to it.

I saw two Black boys at Sears the other day, all tied up [wearing ties], and I was curious. I said, “What kind of work do y’all do?” “Oh, we retail clerks.” See, they don’t want to be nothin’ the old Blacks were. They don’t want to be cooks, and they’re not going to be cooks. You old enough to know what I’m talkin’ about. There was no such thing as no white service station attendant. Now there ain’t no such thing as no Black service station attendant. You never thought of these things, have you? And that’s why the Black race and the white race is getting further and further apart. They don’t understand the Blacks no more. I don’t understand them myself. I don’t know where the hell they headin’ for.

At National Public Radio in Washington, they said, “Aren’t you fearing for your life?” I said, “Hell, no!” And I performed to all-Black audiences. I performed in all-Black clubs. They just laughed. They asked me if that was true. I’ll slap the shit out of one that tell me I’m lyin’.

Like when I was a boy, every Black boy had marbles in one pocket and a harmonica in the other. Now that son of a bitch got a gun in one pocket and a knife in the other. Am I lyin’? What I said had the headline of a Chattanooga, Tennessee, newspaper headline a couple of years ago when I was up there. “Black Man’s Biggest Door Opener Is His Music.” No more.

What was Black music like when you were young?

It was jazz, man, and blues. And spirituals. You follow me? White people would get down on their knees. [Excitedly] There wasn’t nothin’ on God’s earth could humble white people and get to them quicker than music. And they did wonders for Blacks on an individual basis. Like [opera star] Leotyne Price – who the hell you think sent her off to school? A white woman in Mississippi. Who the hell you think sent Arthur Lee Simpkins, who sang in six languages, to school? A white man from Savannah, Georgia. Who you think sent Roland Hayes to school? These are people way older than me. Roland Hayes would be 90, if he was livin’. Rome, Georgia. White people. You understand what I mean?

When you were young, blues was not accepted in parts of the South, especially among religious Black people.

You right. They played it on the street corners.

Was it considered “devil’s music” in your home?

It was devil’s music. That’s right. The guitar was devil’s music to the Christians. They played it on the street corners for tips, just like I’m doin’ right now – Blind Willie McTell, and I could go on.

Did you ever meet Blind Willie?

Sure. Atlanta, Georgia. The guy that Chet Atkins got his inspiration from, Blind Blake, used to set outside.

Blind Willie McTell was active until the 1950s.

That’s right, that’s right. And there’s Pearly Brown . . .

Didn’t Willie McTell play slide well?

That’s right. That’s why I don’t play that stuff no more, man, because it pisses me off. The ones makin’ money with it is the damn English. See, Pearly Brown may still be living [Brown passed away in 2010]. Rev. Pearly Brown – he was on Columbia Records. He was from Americus, Georgia, but he used to walk the streets in Macon all the time. I’ve known him all my life. Oh, yeah.

Who were the big bluesmen when you were a child? People like Blind Lemon Jefferson?

Oh, man, that was the daddy of that shit! Bill Broonzy . . .

Oh, Big Bill!

You know about him, huh? I’m glad to know that, man.

I really like the music when he was young, doing those risqué hokum songs.

You know those blues was dirty back then! They had wrote on there [on the 78 labels], “Not to be broadcast.” You know, it makes me feel good to see somebody that knows something. Some of these people come around to interview me don’t know a damn thing.

People have put out album anthologies of songs like “Pussycat Blues.”

I used to do that stuff, years ago. Just like Doug Clark came out about 25 years ago and revived [Georgia White’s] “Hot Nuts,” and youngsters think he’s the one. That song was a hit when I was a kid. And “I’m Glad When You’re Dead, You Rascal You” and “Your blood run cold, the undertaker pack cotton in your asshole.” And that’s just the way this thing went on record. And it had on there, “Not to be broadcast.” Like you say, collectors got those old records. I went to a guy’s house in Denver and, boy, I’ll tell ya, that guy had all that stuff. That’s the way it was, man.

When did you take up guitar?

I started foolin’ with the guitar when I was about seven, eight years old. I got my own style, man – ain’t nobody sound like me.

Your repertoire seems to go back way before electric music.

That’s right!

And a lot of it goes back before jazz and blues, all the way to the mid 1800s.

You’ve got it! You’ve got it! You know what? So far, you’re the smartest dude I’ve talked to in a long time. You got it right. You know that little amplifier I got? It was the first [Gibson] amplifier that was made, that old Gibson. It was the first one I ever owned. But I still hate electric guitar. I put a pickup on my guitar last year. It saves strings.

See, I just made this trailer. I made this trailer in December, right here. I was playin’ on the outside [before that], and it was hard on the instruments. I tried to think up a way to get something, and I came up with this idea. So it saves the strings. And these flea markets are so noisy, man. Sometimes guys set up right in front of you, doin’ everything. So a guy in Tucson put that pickup on there for me. I like that.

Yeah, my music. See, my grandpa was an old guitar player. He was born in 1821. I guess this is truth for sayin’ that’s why I sound like I do and go way back there. And like the old slave songs, man, they just bring tears to my eyes. They been around for years, and they been hits a lot of times. People don’t even know they’re old Black slave songs, like “Blue-Tail Fly” and “Shortnin’ Bread” – that’s three hundred years old, see. This was the type of stuff my grandpa used to do. And that’s where really I got my inspiration from. And the only dude in the last thirty years that really blew my mind was Mississippi John Hurt.

Oh!

Wasn’t that guy beautiful? He didn’t get discovered until he was seventy-damn-four. They claim he was pretty big in the ’20s.

In the late 1920s with songs like “Stack O’ Lee Blues”. . .

You’re right. God, that man got a beautiful guitar style! He played nothin’ but acoustic.

His syncopated picking sounds so easy, but when you try to get it . . .

There’s a white boy in Atlanta had it down pretty good, man. I said, “Well, I don’t blame you, man. You’re the one makin’ money with it.” And Lead Belly. Lead Belly should’ve got that break Josh White got. I never thought Josh White really had nothin’. He just was lucky and got a break.

I thought Lead Belly became popular in the last years of his life.

Before he died – you’re right. And then “Goodnight, Irene” as soon as he died.

By the Weavers.

And “Midnight Special.” You know, you pretty sharp on it, man. You ought to be. How many people know these things? Like that gal came around, write me up in Phoenix last month. Man, she pissed me off. She didn’t even know her name.

Did you ever see John Hurt or Lead Belly?

John Hurt. Oh, yeah. Lead Belly too. I know the history on Lead Belly, man. There’s a movie out, Leadbelly. I haven’t seen it, but I heard some people talkin’ about it.

I saw it and bought the soundtrack album featuring Hi Tide Harris.

I know a lot of it. See, I know the facts, man. Just like how that song “Irene” came by. See, he’d spent years in the penitentiary, so he made up a lot of those songs in prison – “Midnight Special.” The governor of Louisiana sent for him to come and play for him at the mansion. And he said, “Boy, you made up all them songs?” “Yes, sah.” “Can you make up a song about my wife?” He did “Irene, Goodnight” right on the spot. [Sings opening line.] Governor told the warden, said, “Let him go.” Warden said, “Man, that’s a damn [uses the “n” word] – I can’t let this [uses the “n” word again] go.” The governor said, “I said let him go.” [Lead Belly] got some nice clothes, with starch-on white shirts. In ’49 he died.

What were you doing then?

Kickin’ ass, man! ’49 was a good music year. You know, Pete Seeger got his inspiration from Lead Belly.

That’s also around the time Muddy Waters and other bluesmen began hitting it hard in Chicago.

And the only white person that was out there in that audience was a white policeman. Let me hit you right there with one: I used to raise hell, and how come the whites didn’t dig it? Do you know what, man? I’m gonna ask you a question. No argument, because I’ll tell you. How long whites been diggin’ blues?

Since 1961.

Very smart.

England.

In 1960, I raised so much hell at a white college there in Macon, Georgia. Mercy University. I said, “How come y’all don’t dig blues? B.B. King?” They didn’t know what the hell you was talkin’ about. See, I’d given them “Cottonfield,” “Blue-Tail Fly,” stuff. They didn’t know shit! And then these English guys started digging it. And they come out sounding like they’s Black. I was walkin’ down the street in Mobile, and this guy had this big music store, all open. He had loud sounds comin’ out. I was with a guy, and I said, “You know what? That ain’t no Black man. What the hell is goin’ on?” I said, “Let me see that cover to that record.” Damn English boys.

The Rolling Stones or somebody like that.

That’s right. You know, they said it! They said they got their inspiration from Howlin’ Wolf. Howlin’ Wolf, big as he ever was, was $250 a night – that’s including his band. Oh, man, I worked with those people. John Lee Hooker – I worked with all of ’em. And the damn English. What did the Beatles sing? Little Richard. Oh, man, they’re [i.e., the inspirational bluesmen] all from the South – Georgia and Mississippi and Alabama. Every damn one of them.

And some of the greatest have never been heard. Buddy Moss may still be livin’. Buddy Moss. There’s a guy come from England and wrote a big old thing about him. He come by my house, and want to know if I know if he’s still livin’. And then they made a little jive album on him. I got a copy of it out there, called Rediscovery. He got rheumatism all in his fingers and all that stuff. There was also Guitar Jones from Augusta, Georgia. It’s the greatest ones were never discovered. Never, never. But a lot of ’em, see, they only play on the street corner on the weekend.

I heard this guy talkin’, “Go down here in San Luis Obispo – they do a big thing on blues.” You ever been down there? They have a blues society. See, I was goin’ way back down there to get my musical instruments. Most of these music stores make my ass tired. They don’t know their name. See, old blues players, they use different kind of strings, different kind of harmonicas, different kind of everything. And most of these music stores don’t understand nothin’ but little rock and roll white boy shit. He said, “Oh, yeah, we get all these blues singers.” And that guy had the stuff – Eb blues harmonica. I said, “Most of these stores don’t even know what the hell you talkin’ about.” See, I use a bass string on my guitar that’s a .064 to .070.

You’ll never go out of tune like that.

That’s right. You know big strings, man. And they put them on there slight [i.e., use light-gauge strings], they don’t get that sound. When I’m playing G, that’s Eb. That’s the way the old blues guys did, man. And I want that same kick. You put them little old ordinary strings on there, man, and they pop like thread. The sound ain’t right. And that guy in the store said, “You got one of them big old acoustic guitars, and you want these kind of strings?” “That’s right.” And them Ernie Ball strings is made up right down there in San Luis Obispo. They got a factory down there.

How many guitars do you have with you?

Just one.

What kind is it?

Ernie Ball. Ernie Ball made it. Don’t many people know that. They don’t make that many of them, man, because there ain’t that many people want a guitar that’s that big. That’s the second one I’ve had. I had a Gibson Jumbo, but somebody stole it. I had it ever since the ’30s, and somebody stole that. Gibson don’t make that one no more. And this is my second Ernie Ball. That’s the only thing that satisfy me.

That guitar is a lot bigger than a standard acoustic.

Oh, God, yeah. You can’t even buy no case for that guitar.

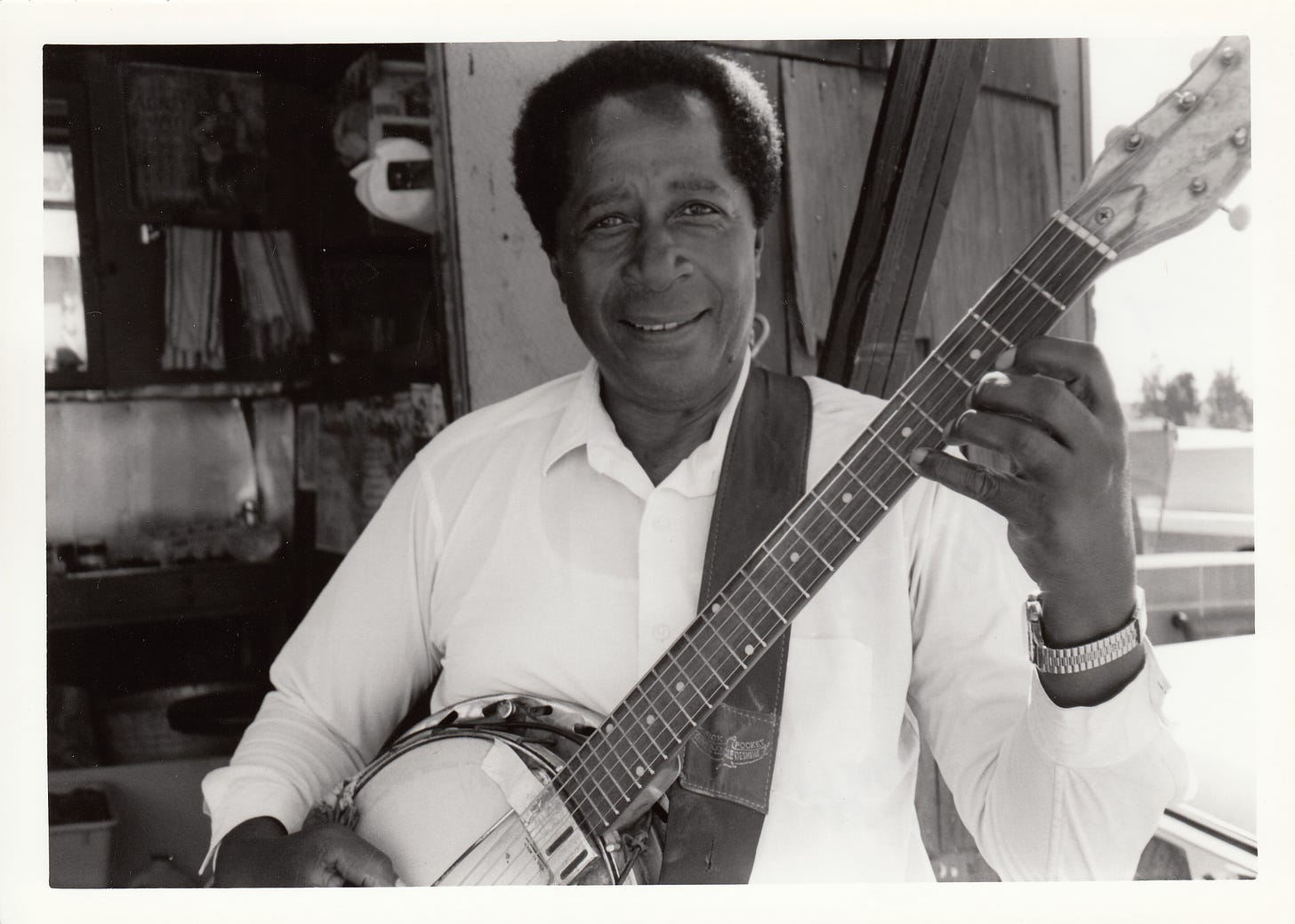

You play a six-string banjo too.

Yeah, a 1748. Old banjo.

Do you know the make of it?

Dobro [Dopyera] brothers. My grandpa had it. I play that sometime – depend on the mood I’m in. But I’ll tell ya, the guitar is better out here, because you got so many Spanish people that don’t understand no banjo. They all understand guitar, and most of ’em got a guitar. The guitar puts more coins in my kitty. Now, whites know where I’m comin’ from with that banjo. But sometime in that damn market you can shoot a cannon down that aisle and don’t even hit a white person, especially when the weather is bad. But back South, and even Tucson, I play banjo the most.

During most of your career were you playing like you play now? Would you be living with your family and going off to play gigs somewhere?

Well, I’ve lived in a hundred different towns, with an address, a residence. Since you asked that question, I’ll tell you the gospel truth. I been away from my family now longer than I ever been. I been in this thing [indicates his motor home] two years, consecutive. The reason is because of this thing. Number two is because the rent is so damn high in California. Only a damn fool or somebody that’s got the money would pay that kind of thing. And I read every day, be intelligent about things. I spent two winters in Arizona; I had a house. A house that cost seven here, you can get in Arizona for three. I got one kid, 14. All the rest of them grown. My kid and wife came up twice in six months. I’ve done this all the time, until the last two years, since I been in California.

What kind of places have you played?

You mean in the last few years, or all my life?

All your life.

Well, we’ll go back to when I started. I started with the medicine show. You know what a medicine show was?

Sure. What was the name of it?

This was Sam’s. Oh, the Rabbit Foot Minstrels were the ones I stayed with the longest. The owner of it is living – I saw him. His last name is Dudley. Real yaller [uses “n” word], almost look like a white man. And I saw him in Pensacola, Florida. He was still livin’.

I don’t know how to tell it but nothin’ like it is. I don’t fool around. Listen to Johnny Carson – them people be nothin’ by lying on shows like that. They got people that tell them what to say. But I say it like it is. And the biggest Black minstrel show in this country, ever, was Silas Green from New Orleans. They had their own damn train. That was in the ’30s and ’40s and ’50s. He was a white man, but all his show was Black. And he married a Black gal. And that man’s daughter is still livin’. Richest Black family in America. She been in Los Angeles about twenty years. He been dead about thirty years. And he left her three-hundred rent houses in Macon, Georgia. And that show was so big, they had their own Pullman cars – about fifty of them.

What did you do at the minstrel show?

I am the world champion hambone beater and jawbone player. Them jawbones hangin’ up in my trailer – that’s the first form of American music!

Beating jawbones?

That’s right. I can’t understand why more people don’t know that. There been songs about jawbones in music stores, and all your jazz bands had two jawbone players up until the ’30s.

Would they beat the bones together or hit something with them?

There’s two forms of the bones. You seen people play the spoons – well, that’s where the real bones come from. I play them too – real, real bones. This ain’t no bullshit – I have plastic bones you can buy in there in a music store today. And you can buy ivory bones in a music store. But the thing they play, that was the beef bone.

Have you ever heard of J.C. Burris?

Oh, yeah.

He’s the only one I’ve ever seen do it.

Is he still living?

Yeah. [Burris died in 1988.]

I’m the only one I know. Now, I had a retired college president, came from Michigan State. Years ago he heard about me and he heard about the bones, and he play the bones. And he was so fascinated he spent a whole week down there with me. And he just said he couldn’t understand how come didn’t more people know about the bones.

Did you play bones in a minstrel show before you started on guitar?

Oh, yeah. See, I started the minstrel show when I was eight years old.

Where were you traveling?

Mostly in Georgia and Florida. I was ten years old before I started playing the guitar. I started playing the guitar first, and then the banjo. I was ten years old. See, they claimed I was the inventor of the hambone, but I’m not. I don’t know where I got the hambone from – I don’t remember. I know I didn’t invent it, but at home right now I got a lot of relatives still livin’, in their early seventies and all, and they said I started it. But right now there ain’t nothin’ I can’t do on the hambone – it would just blow people’s minds, man. I don’t do it in no flea market. Too many people. I don’t even play the bones at the flea market. Cram the aisle all up, but it don’t mean all that much because the only one that put somethin’ in the kitty is the one right up front.

Have you recorded playing bones?

Yesiree. I don’t have an album available, but I got a cover of it right up in that trailer. I don’t have no copies – sold out. See, I have albums, but because of inflation, I don’t have but one available. Just like other people, I been sellin’ them and takin’ the money. Just ain’t been puttin’ it back in the business, that’s all. So I think I’m goin’ in to cut stuff after I get through with the one I got now. But I own eight masters – I got ’em right out there [points to back of truck]. I made fifteen, but the record company never released it. I made two albums in San Francisco since I been here.

Did people come to you wanting to do an album?

Yeah. A guy who’d heard my record. Got a great big studio on Harrison [Street] in San Francisco. Been in the business a long time, and he specialize in old stuff.

Is what you play out here at the flea market fairly representative of what you do?

I’d say that’s pretty representative. There have been times, like workin’ in the night clubs – years ago I had a night club act. I’d have my one-man-band stuff set up for a big night club act, where they had other big bands on the show. You’d have twenty minutes. So I’d come out talkin’, and while I was talkin’, I’d be having my banjo on or guitar, whichever I was gonna play. And by the time I’d get all the stuff on, I’d go into a song. It was mostly blues I played in night clubs. “Cocaine Blues” was my breadwinner for years and years.

The Rev. Gary Davis tune?

No. It’s my version. I got a copyright on my version of “Cocaine Blues.” I sold more records of that than any. I don’t have none of them records, see. “Cocaine Blues” was a big smash in Washington, New Orleans, Atlanta, and Boston. I bought my first motor home, cash, in Washington, D.C., with “Cocaine Blues.”

Have you always recorded under the name Abner Jay?

Abner Jay. That’s the name my mama gave me. Always. That’s right. And I never had a record put out by a major record company. I recorded for a major record company, first time in ’47. And they gonna wait until I die to put it out. They just wanted to get something down for them English boys to copy. That’s all they did. In fact, I cut them son-of-a-bitches out in San Francisco. They kept beggin’ me, beggin’ me. Guy had me over to his house. Went down, he got a $100,000 stereo in his house. I said, “Man, you know what? The lie-ingest people on earth are politicians and record people.” I said, “You pay me some money, right now – cash money. Lay it right down here [pats table]. That’s the only way. I don’t want to hear no shit about royalties, ain’t no nothin’, because there ain’t gonna be no royalties because you ain’t gonna put out shit.” [Imitates record label man] “It’ll be out in December.” I wouldn’t waste a dime to go to the phone and call him.

That’s the way Lightnin’ Hopkins was. He wanted to be paid after every session – just hand him the cash.

That’s right, that’s right. They’re full of shit. Buddy Moss, same thing. And I talked to Columbia Records about Buddy Moss. John Hammond, who was president at the time, when I was in New York. And he said, “Oh, yeah. We made a beautiful album of Buddy Moss.” The guy I told you never could got nowhere? Then the guy in England came over and wrote about him. And I said [to Hammond], “Well, when you gonna put it out?” [Imitates Hammond] “Oh, in a couple months.” Never did, man.

And so they said they gonna put my record out in December, and it ain’t out yet. A lot of them come by my thing [trailer] to talk to me. I cuss ’em. I get up and put my foot in their ass, right down at that flea market. Lyin’ son of a bitches! I did get $300 out of ’em. I shouldn’t have done it. Lookin’ back, I shouldn’t have even . . . . And I told my wife. She said, “Well, you know they gonna bullshit if you don’t get some money. You shoulda got $1000.” And they come on so strong, man. The stronger they come on, the madder they make me.

One of those guys come by the market Saturday. I said, “What’s the deal on the record?’ [Imitates the other man] “We goin’ through the material.” I said, “I know that takes time – it takes at least thirty or forty years to get that done.” I be tellin’ the truth, man. I know what the hell I’m talkin’ about. And let me tell you this – oh, man, this is too strong for your brain. Just bet me some money I’m lyin’.”

To be continued….

###

Abner Jay passed away on November 4, 1993.

I have hours more of interview material with Abner Jay. If you’re interested in my posting another installment of his adventures and outspoken views, leave a message below.

Please support independent music journalism and help me continue producing guitar-intensive articles and podcasts by becoming a paid subscriber ($5 a month, $40 a year) or hit that donate button. Paid subscribers have complete access to all of the 160+ articles and podcasts posted in Talking Guitar. Thanks for your support!

©2024 Jas Obrecht. All right reserved.

I like to pick up old issues of Guitar Player when I can. I recently grabbed this June '82 issue in my local library's discard bin and could recall when it first hit the stands. It was notable at the time for the short note about Randy Rhoads's death. It was also memorable for introducing Adrian Belew to me and changing how I looked at electric guitar forever. But reading it at again after all these years, I was struck mostly by your interview with Abner Jay. It seems to me that, in today's guitar magazines, a musician like Abner would never be featured. This is a shame as his approach to performing and his philosophy of music is closer to what a majority of musicians need to hear. Most of us will not become rock stars but will instead follow Abner's path, living gig to gig, trying to keep an old car or van running, and, if we're lucky, finding a niche for ourselves, like Abner did with flea markets. I wish I had read this article when it was first published. I was eighteen then and saw myself, unrealistically, on a path to rock and roll stardom. Now, in my 60s, I see that my career very much mirrored Abner's, playing various styles of music in venues of all descriptions, at weddings and funerals, in schools, in musical theatre pit bands, on cruise ships, at trade shows, and even a few flea markets. If I had taken Abner's approach to the musical life to heart, I might have been able to appreciate the opportunities I had rather than always feeling like I had failed somehow by simply entertaining people where they lived. At the very least, I would have learned that "fat women" can be a target audience. Looking forward to reading all of your posts.

It's been a year on, but I would greatly appreciate another installment. Thank you.