Steve Morse: The Complete 1978 Dixie Dregs Interview (HD Audio)

Includes Both Audio and a Complete Transcription

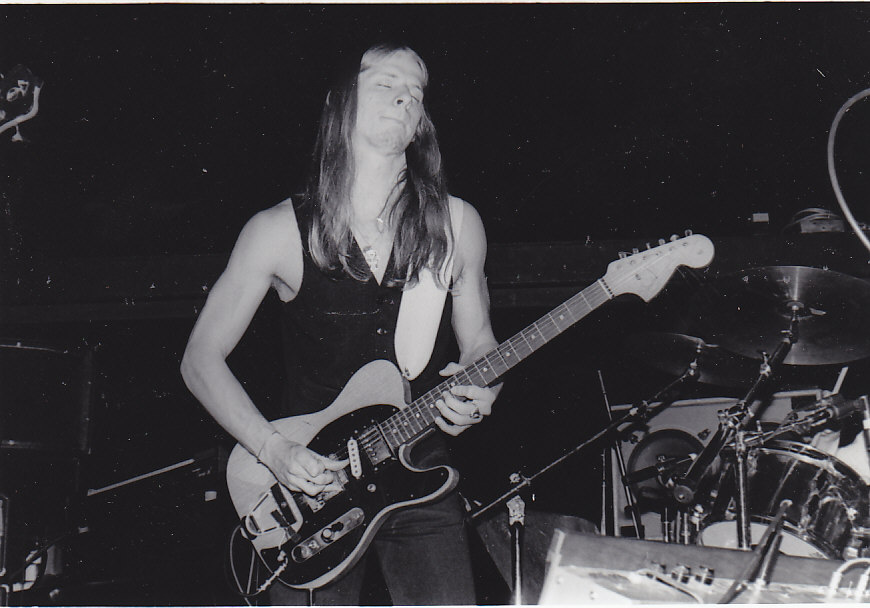

If there had been “best band in the land” contest in the late 1970s, the Dixie Dregs would have probably received my vote. With spectacular musicianship, the quintet wove hard rock, chicken-scratch country, freeform jazz, bluegrass, jigs, Baroque/classical, and other styles into a vocal-less musical tapestry that transcended classification. “We rarely think of labels,” explained bandleader Steve Morse, “but if we did, it would be something like ‘electronic chamber music.’” Writing nearly every note for every instrument, Morse orchestrated the lineup into a top-flight band rather than a collection of virtuosic soloists. Steve’s mastery of tones and techniques earned him the reputation of being among America’s finest all-around guitarists.

Born in Hamilton, Ohio, on July 28, 1954, Morse grew up in Ypsilanti, Michigan. While in high school, he moved with his family to Augusta, Georgia, where he immediately encountered culture shock. At Richmond Academy military school, he befriended bassist Andy West and recruited him for Dixie Grit. That group lasted until Morse enrolled in the music program at the University of Miami. There he formed the Dixie Dregs with West, drummer Rod Morgenstein, violinist Allen Sloan, and a changing array of keyboardists. At local gigs they mixed Allman Brothers and Mahavishnu covers with original songs. The Dixie Dregs recorded the 16-track, limited-run The Great Spectacular album during senior year.

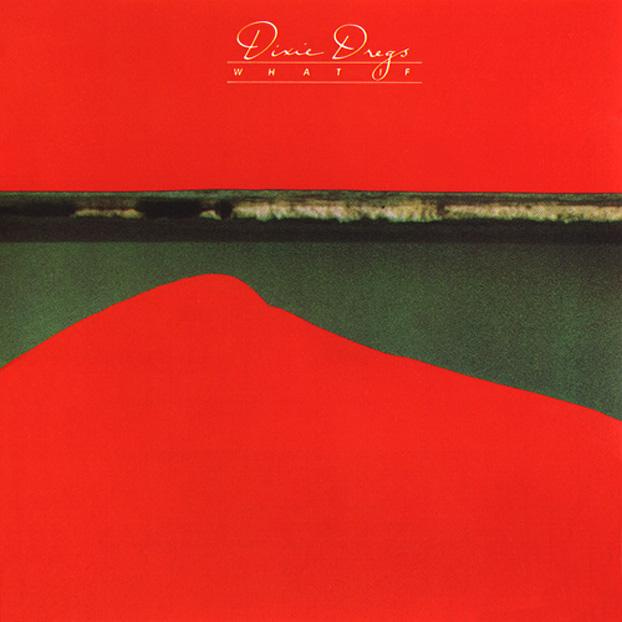

Following graduation, the Dixie Dregs headquartered in Augusta, with Steve Davidowski taking over on keyboards. A shared bill with Sea Level brought them to the attention of Chuck Leavell and longtime Allman Brothers roadie Twiggs Lyndon. Leavell and Lyndon convinced Phil Walden of Capricorn Records to audition and sign the Dixie Dregs. Free Fall, the band’s debut, was issued in the spring of 1977. The fact that the album was completely instrumental instantly set the quintet apart from everyone else on the record label renowned for purveying the “Southern sound.” For What If, the band’s must-hear second LP, Davidowski was replaced by Mark Parrish, who’d been in Dixie Grit. This was followed by 1979’s half live/half studio Night of the Living Dregs. In 1980, they dropped the “Dixie” from their name and signed with Arista.

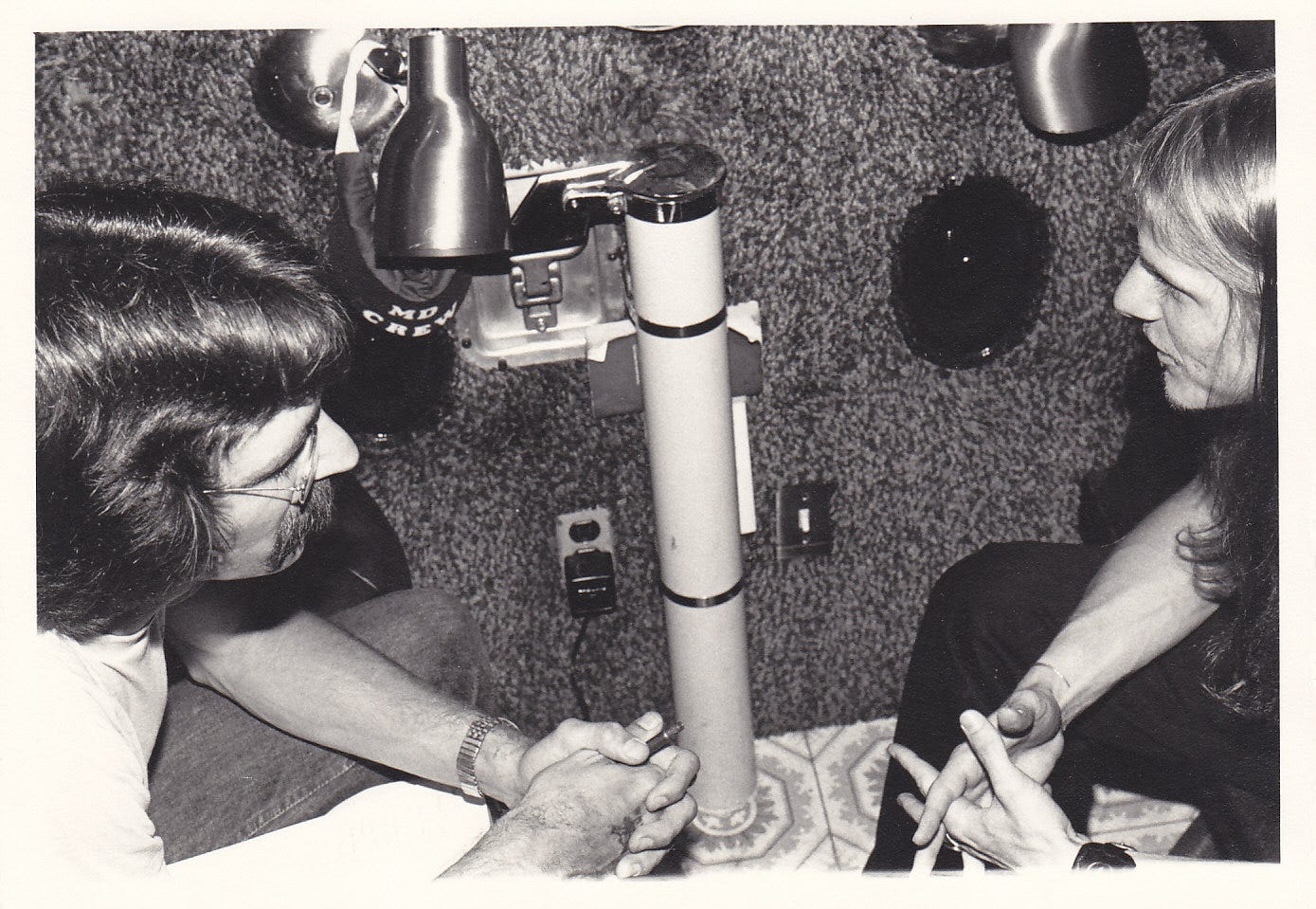

Among the many interviews I did with Steve over the years, my favorite is our first. It took place in Berkeley, California, on June 8, 1978. After sound check, Steve and I settled into Twiggs’ truck and spoke for more than an hour. I also interviewed Andy before the show. As I wrote in my notebook, the Dixie Dregs were stunning that night – “as daring as the Mahavishnu Orchestra, as expressive as Jeff Beck, as evocative as Aaron Copland.” They segued from Zep-heavy rockers to country breakdowns, from breakneck fusion to dreamy excursions into the sublime. Knuckle-busting passages became seamless dialogs in their capable hands. After the encore, I interviewed Twiggs Lyndon about his role with the band. Portions of my Steve Morse interview were published in the December 1978 issue of Guitar Player. Here, for the first time, is the transcription and audio of our complete conversation. Steve begins by talking at length about his one-of-a-kind hybrid guitar and gear, and then becomes increasingly entertaining as he delves into his past.

***

First off, tell me about your guitar.

Okay. I would say that’s the most vital piece of my equipment. If I had everything stolen and I had to start from scratch, I’d try to duplicate the guitar before I even worried about the equipment. It’s got a neck that I’ve had for about 12 years. I bought it when I was just starting. It was a Stratocaster – a brand-new Stratocaster. I took care of it and tried not to scratch it, but the guitar ended up paying some dues. Just for reasons of sound, I came across an old Telecaster and switched the body – just put my neck on the body of the Telecaster. I said, “Wow! It fits.” All I had to do was add one little shim to it. So I said, “Well, if I can do this, then . . . .” So I got courageous.

So there I was with a Telecaster with a Strat neck, and the bridge wouldn’t tune up. I was used to the Strat – individual pieces – and the first pickup squealed. So it was two problems at once. So the first thing I did was put a Tune-o-matic in and saw off the part of the metal plate that holds just the bridge. So it still had the squeaky pickup in it, the feedback from the pickup. But I had a bridge I could adjust, and that was cool. And I had to add a tailpiece while I did that. I found it in an old music store – it’s for a 12-string. It was real short and had 12 holes in it, which is interesting also, because usually I can have an E string going through one of the extra holes, curled up and taped down. So if I break an E string, it’s already there. I just pull it out and it’s only about an eighth of an inch away from the regular E string, so it will go over the saddle with no problem. That makes for quicker changes. Anyway, so I had the tailpiece and the Gibson Tune-o-matic with the original pickups, and I switched from a Vox Super Beatle amp to an Acoustic amp.

When did you have the Vox Super Beatle?

This is way back in the early days – you know, high school rock and roll. When I was with Dixie Grit. So we were the Grit band! [Laughs.] We just made that name up in fun, because none of us were Southerners. “Grits” were rednecks. Anyway, I couldn’t get a heavy enough sound without feeding back, so I had to put a humbucking in. And I started at the easiest place, which is by the neck. You just take a chisel and a hammer and start pounding it out, splice it in. And that was cool, but I still couldn’t get highs. So the next thing was add a Fender humbucking pickup. They’d just introduced it. I went down to the store and they said, “Hey, we got this new pickup in.” “Wow! Great!” I put it in, and I really liked it. And then I took the rhythm pickup and moved it right next to the Fender humbucking pickup, because I said, “Here’s this pickup, and I’m not even using it,” and I figured out a way I could chisel it out and fit it in there. And then for the fourth pickup, there was originally a High A that was supposed to be polyphonic – you know what I mean? But I couldn’t get it to separate that much without going into a whole preamp thing, so I traded it for an original Strat pickup. That was my first guitar, so I had to have that sound.

So I had four pickups. And there was room – just barely – for this thing that Bob Easton had devised, the 360 System. We’d been watching – I think in Guitar Player is where we saw all these ads. He had a pitch-to-voltage convertor that would just take any high-impedance signal and change it to voltage – with some glitches, of course. And Walter Carlos had used a more refined version of that to make some of his sounds on the Clockwork Orange album. I was freaked out – “As soon as I get the money, I’m gonna get one of these,” I said. And it took so long to get the money, by the time I did have it, Bob Easton had developed the Slavedriver. And so we got one of the first ones, as soon as we could do it. What it is, it’s a little six-pole pickup – you can see the poles. It’s almost totally separated, with the wire for each going to this fancy connector that stops at the guitar. So you actually have a wire curling around your guitar with a strain release that you fasten down. And it turned out there was just enough room to squeeze that between the bridge and my lead pickup. It’s a real thin pickup, so I think it’ll mount on any guitar. And it was perfect. And I still have more guitar modifications.

Tell me. I want to hear about them all.

Okay. Of course, I had to add a switch – in an unlikely place for a regular guitarist. It’s right below the picking line, the strumming line. I have a three-way switch and two toggle switches, so that I can have six combinations. In other words, there’s more combinations than I use, but I experimented with them all. Well, you have the four on – each pickup on. And then I have two double. And the reason I didn’t go through a big, more complex wiring is because the other doublings didn’t sound good. So I just figured I’d just put the ones I needed on. I had the switches programmed so that there are several presets you can do. Like, one switch cuts everything off except the Strat pickup. So you can be presetting the other switches for the next sound coming up, and then flick this mini-toggle switch, and bam, you’re in the new sound. I put my switch right below, right by my hand. I saw exactly where I strum, where I pick, and put it a fraction of an inch away. So if I want to, I can just extend my little finger and snatch up the switch without stopping. Another reason I like the Telecaster is because I can reach the controls with my weird picking style. My hand is laying on the guitar and my wrist is moving.

You keep you little finger extended on the guitar.

Yeah, for muting and for controls. I can reach all the controls while I’m playing. And that’s real important. Being the only guitar player, you’ve got to reach for different sounds all the time. So I’ve got two extra toggles and, oh yeah, it’s got Gibson frets on it. The Gibson frets stand up more. Over the years, I would never let anybody plane that fingerboard with each refretting job. It’s sort of scooped out between the frets, and I really like that a lot. It’s a rosewood neck, so you don’t get that slippery feeling that you do when you get sweaty, especially with the new maple neck.

So between the frets, the fingerboard is worn in.

Yeah.

Do you ever bend downward into the fingerboard, like John McLaughlin?

Yeah. When I put vibrato on, it’s so easy with the scoops and the eroded fingerboard and high frets to just really grab a hold of the string if you want to shake it. And that includes all the strings all the way up and down the neck. I don’t just sit there and hold vibrato notes that often, but every once in a while if you use it for emphasis, it will really grab on with the high frets.

Oh, yeah – what else? The pickguard. A friend at Campus Music in Atlanta, Burt Foster, boy, he sat up a long time trying to figure this out. I’d already mounted everything in the guitar, solid – like screwed it down, the way you’re not supposed to do it, probably, instead of mounting it to the pickguard like in a factory installation. So everything was crewed down into the guitar at the right height and everything. I said, “Look. You’ve got to make a pickguard, but you can’t move it.” And I wanted it to go around the bridge and include the bridge. And all my toggle switches were already set in the exact places. And the screw holes. So I said, “Make me a pickguard that will fit everything without having to change anything on the guitar.” I couldn’t figure out how to do it, but somehow he did it. He’s made some interesting designs. He’s really adept at coming up with something really bizarre – well, I consider that pickguard a work of art.

Any other things about your guitar?

No. I think that’s it.

Do you use any other guitars?

No. That was the idea, so I wouldn’t have to switch guitars.

What kind of strings do you use?

Uh, any kind. I mean, I’m serious.

What gauge?

.010 to .040. In fact, every string – they all sound the same to me. [Laughs.] The biggest difference seems to be when they’re new. I mean, when they’re new, they sound a lot different than when they’re old.

How often to you change them?

Well, I believe I accidentally changed them just before this gig, when I found out you guys were coming! [Laughs.] These are Vinci strings [points to guitar]; I got them down the street. I said, “Give me the cheapest strings you got!” [Laughs.]

Did you build your own effects board?

Yeah. Well, there was nothing to it. It’s cut out of a piece of plywood. We were making cases – we made our own cases for a while in the real hard days. Our boards fit exactly in these Armond footlockers that I was lucky enough to score – those were a bitch, getting those. But, you know, military-spec hardware, so they hold up to the road. So I made it where they just drop in there, and just started screwing everything down to it. And Twiggs made a strain relief for a bundle of wires and routed everything that I use through my talk box. You know, I made a talk box – everybody made a talk box at some time. So I had it screwed onto the board, and it was the only big piece of hardware that would hold chassis-type connectors. So he mounted all my speaker ins and outs, all my cord hookups, from the pedals to the talk box, so on one face of the talk box is about 11 connections or something like that, just all bundled up, so we made a snake for me of super heavy-duty Belden cable for everything, and attached it so it would just barely reach in there. And the strain relief that’s on the board clamps down on the snake after it’s plugged it. It screws down. It’s fairly ingenious the way he did it – simple but ingenious. And then the snake goes back into the amps and fans out into a million connections.

What kinds of effects are you using?

Just typical wah-wah, echo. The phase shifter is a – what is it called? – a Roland Boss Chorus Ensemble. It’s nice. It has one speed, and then another effect that you can switch back and forth. And I bypass the actual unit – you know, you just get a two-position, double-throw switch. The reason I did it was so it wouldn’t go through that unit all the time – which I hate when they do that, because all it does it add hiss and stuff. So everything is bypassed. Like the talk box is bypassed – I don’t even use that, so you don’t hear it. So wah-wah, Chorus Ensemble, echo, and a special thing that I use as a volume control – not a master volume from the guitar, but from the preamp out of the main amp to the second amplifier. This control just adds in another amp. You turn down the guitar, add in the other amp, and all of a sudden you’ve got as big a sound as you had before, only it’s clearer. It adds sound to the Acoustic, so that when you turn the guitar down to get a clear sound, it just adds-in two more speaker cabinets. And also I wired in a stereo plug to my Echoplex, which runs to a volume pedal in the snake, so that I can control the echo on and off.

Oh, the echo is actually more complicated than that. It has a separate volume control for the echo, and nothing but the echo goes to the second amp. So you get delay only. So you’re playing through these cabinets over here and switch it on, and all of a sudden instead of distorting and jumbling up what you’ve got through the first amp, all it does is turns on the second amp, which is nothing but the delay. It really fattens up the sound, and it sounds neat, like back in the old days when you used to separate the cabinets. Of course, I ended having to put a volume pedal between the two so that you could preset the volume of the echo and then turn it on or fade in the echo, which is all necessary to avoid surprises like you’re sitting there playing and you turn on the echo and all of a sudden, whoom, whoom, whoom, whoom. It’s neat. You can set the echo to feedback itself and then with the volume pedal turn the switch on and turn the volume off, and just sneak in a little bit. You have to have echo volume, but none of manufacturers include it, of course. They don’t even include an input jack or an optional accessory.

What about amplifiers?

Just rock and roll stuff. V4 100-watt. Well, they say it’s 100-watt; I don’t know what it really is. It’s just an Ampeg tube amp. It’s interesting because it’s got more midrange control than any other rock and roll amp. I’m sure they’ve made some developments since I bought it. I’ve had it five years. I have a spare one on standby too. That goes to Gauss speakers, 12-inch. And the Acoustic goes to JBL 12-inch. The Acoustic is a 150, just basic rock and roll. It distorts a little bit when I really put it to it, but the way that I use it, it turns out that a clean hi-fi amp isn’t as good, because it gets this buzzy, searing edge on it that I don’t find very pleasant. I was never able to make any of that Crown concept work for me – yet. That is, you find a great preamp, and then put it through a Crown and all your problems are solved. I couldn’t get it to happens, because I play rhythm and lead guitar, and that is the problem.

Now you do the composing, right?

Oh, yeah.

How do you compose?

Well, I still haven’t formulated a system. I’ve gone lots of different ways, starting with the guitar lick.

How have you evolved since you first started to compose?

Okay. Well, the very first thing I did on a musical instrument was make up a song, because I didn’t know any. I played piano when I was a little brat – you know, my parents got a piano, rented it. My brother was taking piano lessons. I heard some music on the TV – little kids watch TV a lot – so I copied the music. They have a lot of music on TV, you know. It’s just subconscious. So I made up a little song, and my parents were, “Hmm. This boy is crazy.”

How old were you?

About four or five.

When did you get your first guitar?

Oh, that was interesting! My grandmother found a guitar, smashed. Somebody had dropped it out of a car on the side of the road or something. It was this old Sears. It was cracked, but this was right after the Beatles came out, so it didn’t matter – it was a guitar! And it was great. You know this is sort of weird, because you hear, “Well, my first guitar was a cigar box . . . .” But it’s true. I think everybody’s first guitars were really bad. I took group lessons. It cost a buck-fifty. So I saved up a buck-fifty and took group lessons with housewives and stuff. We were all crowding around, and the guy came around to me. The first lesson was tuning the guitar – he was gonna tune it, and that was it. He tried to tune it, and he says, “Uh, I think we better talk about this guitar. If you want to take any more lessons, you’re going to have to rent a guitar.” [Laughs.] I was shattered, but my parents sprang for it. They rented me a Gibson LG-O, and so that made it a lot easier because I could press down the strings to the frets. That made a whole world of difference. It was like you play it. So I learned chords from that guy, and then went on to play Rolling Stones and stuff.

This must have been 1964, ’65.

Let me think. Yeah, ’64 and ’65. Very good! And I was doing the Detroit music. [Mitch Ryder and the] Detroit Wheels – all that stuff. The Rationals.

What was the first guitar playing that you were conscious of to where you knew you wanted to go into that style?

Boy, I don’t know, because I heard Chuck Berry. I had an electric guitar at one point, but it was a Fender. And I said, “How can he make his guitar sound like that?” Same thing with George Harrison. The Beatles were the heaviest thing that was going on. It was just sounds I was mainly interested in. It was getting one really great sound.

When did you get the first guitar that you actually owned, and what kind was it?

Okay. After I’d rented the guitar for a few months, I really started leaning on my parents, and they got me a Music Master. It’s like a three-quarter-size Fender with one pickup. But the pickup is so far from the bridge, it sounds like a rhythm guitar, and that’s all it’ll ever sound like. Boy, I loved the guitar. It was used, and they got it for real cheap. And I had that for a little while, playing through a mono record player – it was my parents’ record player, a Heathkit 20-watt. My father made a Heathkit amp, and that’s what we had. My parents were not that into music, and I really got heavy on them, because we played some gigs and we got paid four pizzas. My brother was a drummer, so it was me and my brother and some friends.

What did you call yourselves?

[Flustered] Oh, God! This so embarrassing. This is like dropping my pants. The band was called The Plague.

Was this in Ypsilanti?

Yeah. We played up at a high school, just dances and wherever people would put up with us.

When was this? 1965?

Oh, immediately. As soon as I could play a few chords.

What kind of songs did you do? Did you make up stuff?

Not at that point. We were just trying to play with three guitars plugged into one amp, two or three mikes and an organ in the other. You had to kick the bass amp too, to get it to work. Sometimes it wouldn’t work.

Where’d you go from there?

This is what was weird with me – I’d been exposed to all this, my hair was touching my ears and all that, and I was really getting to dig music. It was such a great thing, and we’d learned all the Paul Revere and the Raiders, the Rolling Stones, the Beatles – anything that our singer could sing. I was even singing back then, because my voice hadn’t changed and I could hit all the high parts. And I was a little kid. So then our family moved to Georgia, and I freaked out. Total, complete culture shock. Because as soon as we stepped off the plane and said, “Hello, Georgia,” rednecks started hassling me and my brother – immediately. Because our hair was halfway over our ears, and it was totally unheard of.

Would they kick you out of school for it?

Sure! I mean, from the very first day. I got into a fight with kids my own age, a gang of rednecks. This is the scene: We move to Georgia, it’s burning hot, I don’t know anybody, the music sounds terrible on the radio, there’s dirt everywhere, our house has no lawn. I walk outside and get in a fight with everybody. Go to school the next day with a black-and-blue face, really pissed off at the world, and then they kick me out of school. They won’t even let me register! So that was in eighth grade, and how old are you in eighth grade – 13? And it was in a time in my life where it wasn’t too cool to have too many social disorders. And every week – or every two weeks – from then on, they would just kick me out. Same thing: “Why don’t you cut your hair?” “Okay, sure. I’ll cut my hair.” And then I’d just push it behind my ears and say, “See, I cut my hair.” They’d say, “Okay. Wait a minute! What’s that!?”

Did this antagonism help your music?

No! I quit playing for about a year and half, because there was nobody to play with. Everybody that was in bands dressed alike and played just rhythm guitar or got a solo of about two notes with octaves. It was white soul music – that’s what was happening down in the South. So it was a bummer. But then drugs came along, and changed everything.

When did you start playing again?

I met a guy who was in a similar boat. He was another outcast at school. I knew we would get along as soon as I saw everybody ganging on him.

Was he a Northern boy too?

Yeah. His name was Allen, and he played guitar. And he knew about all this cool stuff that was like sensory overload. All of a sudden, after just quitting music, here’s this guy who had an amp of his own – that had reverb – and a Gibson guitar. And it was a good guitar. He had records, and he had his own record player too, in his room. So we could go up there and just play records and play along with it. He would come over and jam with my brother, bring his amp. His parents would drive him over. I mean, he was a freak! He was a hippie, a little baby hippie. We got into drugs together, and that helped our music because there was no social life whatsoever except being underground in that kind of an environment.

What city was this in?

Augusta, Georgia. A military town. They had Fort Gordon there, lots of rednecks, and G.I.’s. So we would hang out. Slowly, of course, it spread. There was soon twenty people that knew about drugs and other kinds of music – Jefferson Airplane. There was twenty people who knew who Jefferson Airplane was. All the underground music and the drugs and everything really is what got me back into music. The movement. It saved me from where I was at, because then it was great to not be like anybody else, whereas in Michigan I was a normal person. Then I got used to being a freak – I just couldn’t be a normal person anymore. Everybody expected me to be different, so I was. I didn’t care. So we started playing at a coffeehouse. It was called the Glass Onion.

What kind of guitar did you have at that time?

I had that Music Master just for like a year, maybe. Then my parents loaned me the money to get that Stratocaster, which I got brand-new.

And you still have the neck.

Oh, yeah. So the Stratocaster was still the instrument, and we started playing at a coffeehouse – me and my brother, and we had millions of different bands. But it was at that coffeehouse that all the heavy music started happening, because you could just go down there and play for 40% of the door, anytime. And it was every weekend.

What kind of music were you playing?

Led Zeppelin and Hendrix, The Who. You know, just the heavy underground music at that time.

Had you started composing by then?

Yeah, yeah. In fact, that’s how I did it. It was me and my brother. We’d just jam and get a bass player over there, and we’d just make up arrangements of tunes and then finally just make up tunes. Because it was easier – if a guy didn’t know any tunes, we’d just make ’em up. And then I met Andy three or four years after I moved to Georgia. This was in ’68 or ’69. And it was the same thing for him. This time, I was in tenth grade at Richmond Academy, a military academy. It was a public school. Now, you had no choice about going there. And what they’d try to do is that every male, every guy, had to take R.O.T.C. And you know about that – they cut off all your hair and make you wear a rifle. This was a public school! I could not believe it. And I knew enough about the United States Constitution to figure that that just wasn’t normal. Anyway, I got out of it by first saying I was in the band, and when they found out I wasn’t in the band, I said I was into music, and I was taking music appreciation. And I got into music appreciation. By saying I was in the band, it got initially me out off the R.O.T.C. And when they found out I was still in music appreciation class, they didn’t stick me back in it. So I escaped R.O.T.C. – brush my hair behind my ears and avoid capture!

Andy was sitting behind me in a class. He was a new kid. He moved from Atlanta, which was the place to go. You get all the drugs there, clothes, bands, underground music, free concerts – the Allman Brothers! Atlanta was where it was at. And Andy moved from Atlanta to Augusta. He walked in, and he had long hair too. It was like, “Hey, man – wow! You got to come over to my house. And you play bass? Wow! This is too much. This is perfect.” The next day, he had all his hair cut off and he had an R.O.T.C. uniform on. Yeah, he paid some dues there. So anyway, he was the new bass player. So we would do gigs. Like, we made up our own little set to play a gig one time. We would recruit drummers about each week. There was a lot of people that could play sort of okay – nothing great.

What other kind of musicians would you play with – keyboardists?

Sometimes. There was always guitar, bass, and drums. Yeah, we did have a keyboard player, a regular guy. His name was Johnny Carr. He was good, real dependable guy. He was straight at the time, but he was great. In fact, he had never even touched a drop of alcohol or smoked a joint. He is the straightest guy I’ve ever met in my life. Anyway, he was our keyboard player for a while. But the thing that helped develop our music was that I could sit and jam with my brother, who’s a drummer, in our house at any time, and then just get one or two people over and we can instantly start making music. We got affiliated with a guitarist who could sing, so we started making our own music. At that point, everybody contributed. I’d say, “Well, look, I got an idea here,” and he’d say, “Okay,” and he would make up words. In fact, I think he’s very near a musical genius, just sitting rotting away in Augusta right now. But he still does it. He’s just excellent with coming up with words to go over anything, and really nice melodies. So he was the lead singer. The man’s name was Frank Green.

When did you band start?

It’s so fuzzy to me. That was our main thing. Like in Augusta, the biggest band we had was Dixie Grit, for that area. For instance, one other version we had was we got a band together to play a battle of the bands. This is right before, and it was totally instrumental. It was me and a keyboard player and our drummer. We just made up a title. They said, “You have to have a title,” while we were waiting in line to get the registration so we could enter. They said, “What’s the name of your band?” I didn’t know we had to have a name for it, so we said, “All right, we’ll call the band Three,” because there was three of us. And we did a twenty-minute set of all instrumental music – Beethoven and “Greensleeves” on solo guitar, and then heavy stuff, like Cream – just instrumental versions. They weren’t ready for that. That’s all we had, twenty minutes. We did good. And Frank’s band was a white soul band. He was singing, and they were all dressed alike, and the judges loved them. But they still couldn’t stop us. We almost won – we got second place to them. I was pissed! I hated the guy. But it turned out that he felt stifled doing that and he liked what we were doing, so we got together with him and turned underground. This was about 1970, maybe.

What happened from there?

Well, we had Andy playing the bass, my brother playing drums, Frank singing, and Johnny Carr on the keyboards. We played gigs, and we went to high school and tried to exist doing that. We made some money – it was pretty good.

How did the Dixie Dregs come about?

Okay. I heard a guy play classical guitar in Augusta. His name was Juan Mercadal. He was a concert guitarist who knew people in Augusta, and would play cheap enough to where Augusta could afford him. He blew me away – totally! I said, “God, this is too much! I can’t believe it.” Sensory overload, you know – tilt, everything. Because he’s just a great classical guitarist, and you know what that can do to you, seeing that for the first time? I’d never even heard it – I didn’t know what classical was for. I could pick it with a pick. So I saw him play, freaked out, and found out he was teaching at the University of Miami. I was gonna be an electrical engineer, right, so I could make odd devices for sound effects. So I said, “Forget it!” and started concocting my scheme to get into college, because I was about to become a drop-out. They were hassling me about my hair. There are so many simultaneous plots all at once! Alright, let me see if I can keep it coherent. I heard him play, and I knew I had to go there. And Dixie Grit was happening. We were getting gigs. We were opening up shows at the local auditorium. But the school had been hassling me constantly, for the last three or four years, about my hair. The public school system really hated me.

Oh, God. This is another anecdote I have to inject in here. The year of high school that this happened, it was eleventh grade. I was doing good in school and everything. I finally had it together. So I had a short-haired wig, and I said, “Now, for once, I have the upper hand here.” There was a new rule that your hair can’t touch your back. Before then, I had to wear collarless shirts so it wouldn’t touch my collar and it could still be longer. But this time I had it licked, so over the summer I could let my hair grow without fear.

So you wore a wig?

Yeah! Starting about eleventh grade. Everything was cool. I mean, it was a drag – it gave me a headache and everything – but I got all my friends into doing it. Everybody kept saying, “Man, this is such a drag.” I said, “Look [points to head]. For forty bucks. That’s all you need. Just pull your hair in a ponytail and stick it up there.” I mean, everybody knew. The teachers just thought I was some kind of freak, you know, with weird-looking hair. And when they found out about it, they had a special meeting at the Board of Education and banned wigs! Can you believe that? How can they do that? It’s against common sense. A wig? I mean, girls can wear wigs, but boys can’t. “You can’t wear a wig.” You couldn’t even wear blue jeans. This was 1970 or ’71. They were behind the times there!

So they had this happening. They were gonna ban wigs. They had officially passed it. So we got a march together. I organized it and got it together, but I was sick that day. Really sick. So I drove the car – I finally learned how to drive – and I drove the car to the top of the hill to the Board of Education and looked down the long hill. And with the police escort, there was all my friends, carrying signs. It was such a sight, and we got an interview out of it on TV and started raising enough of a ruckus to where we almost got the American Civil Liberties Union to do something about it, but they wouldn’t. The ordinance passed, and so I sat there waiting day by day to get kicked out of school. Everybody got picked off one by one. And the principal was my friend!

I was the junior class president by that time. I’d gotten such an underground thing happening that I had enough votes to become the junior class president. And one of the goals was to get our band to play the junior-senior [prom], because you know how much they pay for junior-seniors. But the teacher that stood by at the class meeting hated me, so she was anxious for me to get kicked out. So all my friends got picked off one by one. They would cut their hair and throw away their wig. I just said to myself, “I’ve done this too much. They don’t even know what color my hair is or how long it is. They just can’t do this.” So they said, “You’ll have to go and come back when you cut your hair.” I said, “Yeah, well, I’ll see you later,” and cleaned out my locker. And there I was, stuck. I said, “I’m not going back to that school. I need to find a normal school.” No luck. I called up other counties – we were near South Carolina, and South Carolina didn’t have this kind of thing. But they wouldn’t let me go to school there. So it was bad. About three days later I had to tell my parents what I was doing when I got off the bus and came back. And so I told them, and they freaked out. They said, “You gotta cut your hair.” I said, “No, I’m not.” So for a little while I went to a Catholic school, where they were very merciful about it. I just had to wear a tie and I paid a non-Catholic tuition, which is weird. Not being a Catholic, they charge more. I went there for a while, but I didn’t want to finish high school. It was too much more work. Plus, I couldn’t afford it. It was a lot of money.

How’d you get into the University of Miami?

What I did was I started with a special program where high school students could take college courses in the summer and be grown up. So I took a math and piano, of course, and got the SAT’s and all the stuff you need to get when you’re a senior, even though I wasn’t a senior. I had credits in the local college and I had good SAT scores. So it actually turned out that I could transfer without a high school diploma. So we tried it, and it worked, maybe because the University of Miami was a private school. The next thing I needed was an audition tape with me playing classical guitar. So I got a classical guitar and this book that says You Too Can Play the Classical Guitar, and I learned a piece from it.

Did you read music?

No. I made up some tunes for the audition tape, as a matter of fact. But for the actual audition, they sent me a letter saying you have to read music. So I learned a Bach piece – God, it took days. I mean, I could figure out what the notes were, but I couldn’t read it. So I learned that in whatever fashion I could. There’s no classical guitar teachers in Augusta, Georgia. So everything was cool. The band had to sort of break up, though, because of me, because I was going on to higher education. Everybody was pretty bummed out at me, but that didn’t last long. They all got gigs. So down there I just suddenly started learning everything about music – it was like magic.

Did you learn to read music while you were at Miami?

Yeah, that was the first thing. They immediately spotted the flaw in my education! “What’s this note?” “Uh . . .”

How long were you down there?

First year and third year and fourth year. The second year I spent in Augusta. I went down for a year and then came back, like on vacations and stuff. I said, “Listen, man, it’s incredible! Look at all this.” I started turning everybody on. Everything was looking up because I could suddenly write more things and do more. It was a whole different world. I was suddenly learning everything.

Were you studying classical guitar?

Yeah, I was trying. Well, they wouldn’t let me be a classical guitar major, because I couldn’t play. God, there’s so many funny stories in my life. I played electric guitar on the application, right? So they said, “Okay, you’re a jazz guitar major.”

There were some good teachers down there.

Yeah. By my third year they had Pat Metheny working part time, Jaco was teaching bass lessons, and Michael Walden the drummer was there – I’m not sure if Walden was giving lessons or just hanging out. I had the opportunity to jam with him once.

Did you meet the rest of the guys in your band there?

Yeah, late in my college career. Once again, I was standing out from the crowd because I would bend notes and put vibrato on improvisations.

Was this on acoustic guitar?

No. God, it is so confusing, even to me, what I did there. I was a jazz guitar major who played a solidbody electric guitar and whose principal instrument was classical guitar. In other words, I didn’t take guitar lessons on electric. It was just classical, whereas the other guys got down with a jazz guitar instructor once a week. That’s the way I wanted to do it, was to take classical lessons. And I would do anything just to do that. So I finally got to take lessons with Mercadal, and it was great. He was a master, and he inspired me a lot. But meanwhile I was having to deal with the jazz department, and I could just play blues and rock and stuff. So they didn’t like me too much, especially when I started playing over changes, bending notes and not getting a typical jazz sound, which you can just imagine with a Fender guitar. They were really freaked out, and I was freaked out, because I didn’t think it mattered whether you put vibrato on a note or the tone of your guitar. And then they started easing up. As I got better, they got nicer and everything. So I said, “Well, look. This is too much jazz. Can I start a rock ensemble?” You have to take a certain number of ensembles each semester, so I just said, “I want to do my own band and not be a jazz band. Is that okay?”

Is this how The Great Spectacular album came about?

Yeah, later in there. There was one rock ensemble that played sort of jazz-rock, which was mostly jazz. So I said, “Let me do another one, and it will be more of a rock ensemble.” They said, “Okay,” so it was Rock Ensemble No. 2. They put it in the catalog, it was in the books, it was an ensemble. It was so official, and we got a credit each and a grade and rehearsal room, so we took it from there. And that’s when I really started doing nothing but writing for the band.

Is there where you brought together the current member of the Dixie Dregs?

Right. In a few months, it evolved into the members we have, just with a different keyboard player. In fact, what I had to do was make Andy move down to Florida. He was going to a state school in Atlanta by then. He was taking cello or something really weird, so I forced him to move down so he could be in the rock ensemble. Because the rock ensemble was so hip! We had a great drummer – I couldn’t believe the drummer. Same guy we got now [Rod Morgenstein]. We had a lot of keyboard players.

How did you start gigging outside of school?

Oh, it was easy, because you have to do a jazz forum for all the students. And if you can get by that without losing your mind, having all your instructors and friends that are musicians looking at you five feet away – if you can do that, then you can play any gig. So we played at the school’s Rathskeller, and it went over so good because we did some Allman Brothers tunes and Mahavishnu mixed in with our original stuff, just to stretch it into a gig. It went over so good we couldn’t believe it. We said, “Well, if these New York people can get off on it” – even though it’s in Florida, the people are from New York – “anybody can.” And we just went from there. We got gigs with the Musicians Trust Fund, where they pay you to play for free – you get twenty bucks apiece or something, and they subtract work dues from it. It’s all union stuff. We did that for two years in school, the rock ensemble, and it started to become an underground thing at the school.

Anyway, my senior recital was great. I felt so good. I was so happy with the faculty by then. They were letting me do my own thing. This first part of my senior recital was all original music that I’d written for classical guitar. Just that, and playing it. Of course, playing it was a bitch. Writing it’s easy, because you can do that at home! [Laughs.] The second half was the rock ensemble, so all I did was music that I’d done. It was a departure for the faculty, because usually they say, “Alright. One jazz ballad. Two swing tunes. One Charlie Parker tune.” But they bent over backwards to let me get away with that.

By then, they’d just put a 16-track in the school concert hall. They were still working the bugs out of it. Each senior who was doing a senior recital was supposed to get some 16-track time, to record it and rehearse. So I said, “Well, look. Let’s just do a two-track, and let me come in at night with the guys.” They said, “Well . . . Okay.” We got in there for two nights and recorded ten tunes. So we had a 16-track tape, and me and another student mixed it. Nobody knew what was happening with the board, because it was just put in. I had some money I’d saved up for this purpose – I’d been planning, getting out of school, for a long time. So I was ready. We had money to press albums with it, so we had albums to send. We started blitzing the record companies with demos. Everybody got out of school about the same time. Moved up to Georgia – including our drummer from New York. Same town, Augusta, which had mellowed quite a bit since. And we were able to play there any time and draw a crowd. We had a few gigs that we could get to sustain life. Back then, we could live on forty bucks a week.

How did you end up on Capricorn?

We put the demos everywhere we could. We spread ’em around, and made a lot of noise. And people said, “Wow, that’s a weird band.” But nobody was willing to do anything, because they said, “It’s instrumental. You can’t do anything with instrumental music.” So we had to go and pay some more dues, and started getting a following in Atlanta. That grew more and more, and the actual Capricorn thing happened about a year-and-a-half later, after we’d been doing gigs. This was about’75 to ’77.

When did Capricorn pick you up?

Right before New Year’s – right around Christmastime, right before ’77. The way that came about was the Allman Brothers had broken up, and Chuck Leavell started Sea Level. They were just doing small gigs, trying to get tight. And we got on a gig in Nashville, and we had a little following there. So we opened the gig with them, and freaked out Chuck and Twiggs [Lyndon]. Twiggs was there looking for a gig. He was hanging out with the other roadies in Sea Level, just saying, “Wow. The Allman Brothers broke up.” He couldn’t believe it. He was just deciding he needed to start getting another job. I wanted to talk to him, because I knew he was famous as a roadie. I wanted to talk to him, but I knew we couldn’t afford him, so I was feeling sort of depressed about that. So we finished playing, and Twiggs said, in short, that he would work for nothing – whatever we could give him – and he’d let us use his truck. Because we weren’t making any money. So I said, “Okay. We’ll give you whatever we can.” And we started with him.

And then the next day, him and Chuck Leavell and a guy from BMI that was at the gig called up Phil Walden and just gave him this whole big pep talk about the band. Not trying to influence or anything, just saying, “Wow! We like this band.” So we’d been trying to get Phil to hear the band, of course, him being worth millions of dollars and everything, and us just being a band with nothing happening. So he agreed to do a personal audition. So we played at a disco club, on the dance floor, in Macon. He liked the band and said, “Okay, we’ll do it.” So we got the contracts together, fat city.

How soon were you in the studio?

Good question. It was really a while. It took a long time to get the papers together.

What did they have you doing in between?

Nothing. Nobody was gonna say a word until everything was signed.

Tell me about cutting your first album.

The first Capricorn album? Okay. We tried the concept of a total rhythm section at once. In fact, we had all five of us playing at once, in a little room to where there’d be leakage from the guitar and violin and bass if we played through amps. So my amp was turned down and muffled, and everything else was direct. And that was cool for playing together, but the sounds really could have been better. We went back and overdubbed those parts that were mistakes and awful sounds, like a guitar turned down low and a direct violin with a Barcus-Berry [pickup] – can you imagine that? It’s real squeaky. So we overdubbed just to get a better sound and fix some of the playing. Nothing really spectacular happened. Well, there was one thing we did that I’d just done at home with the tape recorder. They had to track some backwards guitar – you know, that’s one thing I’m into doing, doing backwards guitar that does melodies rather than just this aimless soloing. So our producer suggested we do that too, which I never thought we’d put on an album, and that was great. It’s just eight tracks of guitar and synthesizer and stuff.

Any change in strategy for the second album?

Yeah. Okay. One of our idols was Ken Scott, from what he’d done with Mahavishnu and Stanley Clarke. He produced the second album [What If]. Somehow luck had it that he finally heard some of the stuff we’d sent him, or something like that. All of a sudden, we found out we could do an album with Ken Scott – if we went in the studio the next week, or something ridiculous like that. We went, “Wow! Okay, sure, we’ll do it!” So we started frantically packing everything. And his strategy was, record more than you need from the very beginning, make every instrument sound good, regardless of what you have to do, and don’t settle for anything shitty. So we started with drums. He got great sounds. He is just a master! I learned a lot watching him. I mean, God, it was really great, because the budget enabled us to do that one instrument at a time, which is about the way we did it.

After the drums, what did you lay down?

Everybody played along with them, but Ken was just going for the drums. Then bass. And then the tape machine started fluctuating the speed, and that set us back. You can’t hear the pitch with bass and drums, unless you have perfect pitch, you can’t tell. But that bass was wavering half a pitch from the beginning of the tune. We couldn’t tell until we went back and tried to put keyboard with it and discovered the bass was slowly getting higher or lower, depending on which part of the tape it was on. It was on everything, so we had to re-do the bass, and we got behind schedule. Then we did keyboards and then violins. And last, of course, guitar. Like, “We’ve got no money left, not time left. Let’s do the guitar.”

What is the difference between your studio and live playing?

Wow, that’s a good question, because it is different. I think the main thing is in the studio, it’s hard to get wound up. In that studio, it was always freezing cold. Your fingers are cold. And usually I was in there all the time, listening to the other guys and listening for mistakes too. You get sort of tired doing that, and then all of a sudden, “Let’s try a guitar part.” And bam! – you’re out there. You can’t warm up, and it’s so ultra critical – the tuning – compared to just playing. When you hear a whole band, your ear will accept a slight fluctuation in the guitar pitch, because you’re hearing the mix with the piano or something. But when you hear just the guitar blasting at you through headphones or speakers, in such a sterile environment, it can really bum you out if you can’t get it in tune. So we were able to get by all the tuning problems, but it makes you so self-conscious, the fact that you’ve got to be in tune, you’ve got to have new strings on there every day you’re cutting, you’ve got to suddenly play – like all of a sudden, “One, two, three, play!” And that’s not the take, and you gotta sit there and wait while they adjust the mike. The fact that it’s not as spontaneous or natural – that’s the main thing that impresses me about the studio. You can get great sounds, but it’s harder to play in the studio.

What’s your strategy of interworking lead guitar with violin?

It’s an arranging concept. The violin naturally ends up doing a lot of melodies, but we try to use them on counter melodies and on some accompaniment. The guitar can go either way, of course – chords and lines. We try to use the violin-guitar as the climax part of the tune, for the strongest, most homogenous melody sound. Because naturally as you can tell by listening to any Mahavishnu tune, the guitar and bass is what was the original idea of the band, that the guitar and bass could play lines together. It’s slowly evolved to where the guitarist has to be with the violin more.

How do you work your playing with the bass?

I try to get him into a pattern with the keyboard player. A lot of the bass is strictly planned out, just so that everything will be covered, so that there will be no clashes or anything. We have the bass doing unusually complicated – well, not complicated, but more notes than usual, because he gets such a clear sound, and he can do it. He’s got the chops to.

How do you look at the Dixie Dregs in relation to the other so-called Southern bands?

Well, it started out as a joke. “Wow, look at us – Dixie Grit!” When that broke up, we just were left with the name Dixie Dregs, because that’s all that was left of the band – two of us, me and the bass player, so we were dregs. [Laughs.] We just kept the name just so people would know us around there. I like country music and everything, but I wouldn’t say that we were a Southern boogie band or anything. We all love the Allman Brothers – really, a lot – but we’re nothing at all like what people associate with the Capricorn Southern bands. So now, of course, it turns out that there is a little bit of a problem from a marketing standpoint, us being the Dixie Dregs on Capricorn and then doing jazz-rock-classical-bluegrass music. I view it as it’s good. I view it that us and Sea Level are a little bit different than everything else in the South. It’s good, because it singles us out. We’re not lost in the shuffle, like you would have with a typical New York or L.A. jazz-rock thing.

What would you like to do with your playing in the future?

Hmm. Another good question. Wow. I’d like to incorporate more of things that people don’t use. I just try to do as much as I can with what’s available, and it turns out that there’s so much more available than people use. Of course, the classical concept – playing two lines at once – would be easy to develop once I can get my classical electric guitar happening, which just takes a little bit more money. I won’t even go into that. And that’s using fingers to pick. And with electric guitar, God, the expression is so incredible, with being able to change pitch and everything. I’d just like to use more orchestrations coming out of the guitar, just different sounds.

Let me strike all the last five minutes of talking. Let me start over. Okay. Yeah, I’d like to incorporate more of the idea of the classical guitar into the electric guitar because it’s so much block parallel motion usually with the guitar, except in the case of the jazz guitarist. And then with the jazz guitarist, the concept is, “Well, it’s cool to play jazz guitar, and you just use one sound.” The thing to learn from jazz guitarists is the fluid, linear motion and, of course, the harmonic advancement. But the thing to not take from a jazz guitarist, in my opinion, is the one-sidedness about the electronics and sound. There are so many advances now that there’s really no excuse to put people to sleep when you’re doing a solo. A guitarist now should be able to just sit down by himself and entertain people with all the sounds. So I feel real strongly about effects that can be used for effects, rather than the jazz-rock concept, which is turn on a phase shifter and a lot of distortion and leave it on and play a solo with all 16th notes as fast as possible, which is just the same as having one sound to me.

So incorporating almost polyphonic concept into the electric guitar would be interesting. With the synthesizer, it will be possible. With the distorted electric guitar the way it is now, it’s hard to do two things at once, unless you get into split pickups, where you have the bass strings going into one amp and other others going into another. I’d like to get into all that, into splitting the guitar up into different sounds so that you can play polyphonically. If I had the money, I’d have Bob Easton’s supremo setup right now – you know, the six Slavedrivers, one for each string.

Two more quick questions. When you compose, do you score it all out for the band?

Sometimes. Each tune is really different. I hate to say that, but in the rock ensemble, I wrote out everything and just handed out charts. With the band, lately I write stuff out on request [laughs]. I think it saves a step if you can memorize it right on the spot rather than read it. That way you don’t have to carry it around to rehearsals or to the first gig, like some people would. Back in the old days, if you had music stands, that was embarrassing. So it’s better for me, of course, since I hate writing music out. You know, by the time you’ve write out a whole tune for every instrument, you could have written another one – or you could have thought of another one. I think. So it’s a waste of time for me to write down music.

What kind of picks do you use?

I think it’s a Kay nylon pick. I think it’s pretty heavy – it doesn’t bend. And it lasts longer. I pick on the side of the pick. That way you get twice as much life from it, because each time you pick it up it’s one side or the other, rather than using the point. Since I hold it with three fingers, holding it on the side gives me more to hold it with. I keep my picks for about six months – each pick. I use it about six months.

Last week Jorma Kaukonen told me he’d used the same pick for years.

It’s amazing, the things you can get yourself used to. You know, when I switch picks, it’s like, “Whoa!”

You know, this is one of the most intelligent interviews I’ve gotten.

Oh, God! You must have really been doing some! I feel like what I’ve done is put such an unbelievable glut of disconnected anecdotes into your tape recorder. It’s gonna be entertaining. I mean, if you can make sense of that, my hat’s off to you. You know, this is great. It’s a complete thrill to me to do it.

###

After our interview, Steve went on to play in the Dregs, the Steve Morse Band, Kansas, Deep Purple, and Flying Colors. I’m happy to report that he’s still among the most gifted and exciting guitarists out there, and he’ll be touring the U.S. in 2023 with the Steve Morse Band. For more details, visit his official website: Steve Morse Official Website

Thanks to Steve Morse for permission to post this interview, to UNC’s Southern Folklife Collection, and to engineer/producer Nik Hunt for his sage advice and superlative work improving the sound of the original interview tapes.

© 2023 Jas Obrecht. All right reserved.

Edward Van Halen inspired to pick up the guitar but Steve Morse inspired me to see BEYOND the guitar, in terms of musicianship and songwriting. Steve is ABSOLUTELY in my favorite top three favorite musicians of all time ( with Edward being number one and Joe Satriani being number two followed by Steve at three ). And, Morse holds my concert record in terms of seeing him/his groups perform in concert ( over a dozen times-Dweezil Zappa is just under Steve with under a dozen ).

I remember seeing Steve & the Dregs back in the late 80's, maybe early 90's in a Lo-ceiling-ed place behind an Italian restaurant in the Ballard neighborhood of Seattle, Wa. It was a popular place for so many groups, but it's all gone now.

What a sound Steve & the group had. But WAY too loud for the place & the low ceiling. He was playing a Solo of some kind when he stepped on some kind of Pedal (a Boost of some kind , but more than that). It was SO loud yet startlingly different from anything I had ever heard live. I was walking to the restroom & it stopped me in my tracks. It was amazing, but the volume drove my wife crazy. It was just too much.

I don't now exactly what he did but I have never heard this sound before or since. I once happened upon something like it myself. Alas, I never made note of what I was using or the combo I had found while recording something.

What a fine Guitarist he was / is. Unfortunately I read he may be retiring, or backing off drastically due to a health issue with his wife ? Not sure if it's true or not. Too bad