Sir Arthur Conan Doyle imbued literature’s most enduring “consulting detective” with both extraordinary and very human qualities. Sherlock Holmes has keen powers of observation, unassailable logic, and a bloodhound’s zeal for tracking prey. He also loves music. One of the most enduring images of Holmes is with violin in hand, playing something from the classical canon or riffing around as he ponders a case’s complexities. This image of Holmes appears in the original stories, as well as on the silver screen and television.

Who can forget Basil Rathbone’s Sherlock Holmes picking up a violin, much to Dr. Watson’s consternation, during the 20th Century Fox films of the 1930s and ’40s?

The strange scene of Holmes playing to flies in a glass, from 1939’s The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, was recreated in the 2009 blockbuster with Robert Downey, Jr.

During the 1980s and ’90s, and Britain’s Granada Television prominently featured Patrick Gowers’ haunting violin theme for the opening credits of its Sherlock Holmes series. This part was performed by Patrick’s daughter, Katharine Gowers. In various episodes, the brilliant actor Jeremy Brett, arguably the foremost Holmes portrayer, is seen playing violin and going into a rhapsodic trance while attending concerts.

Theme from the Jeremy Brett series.

The more recent updating, the BBC’s excellent Sherlock, likewise features the master detective with bow in hand.

Enter Sherlock Holmes

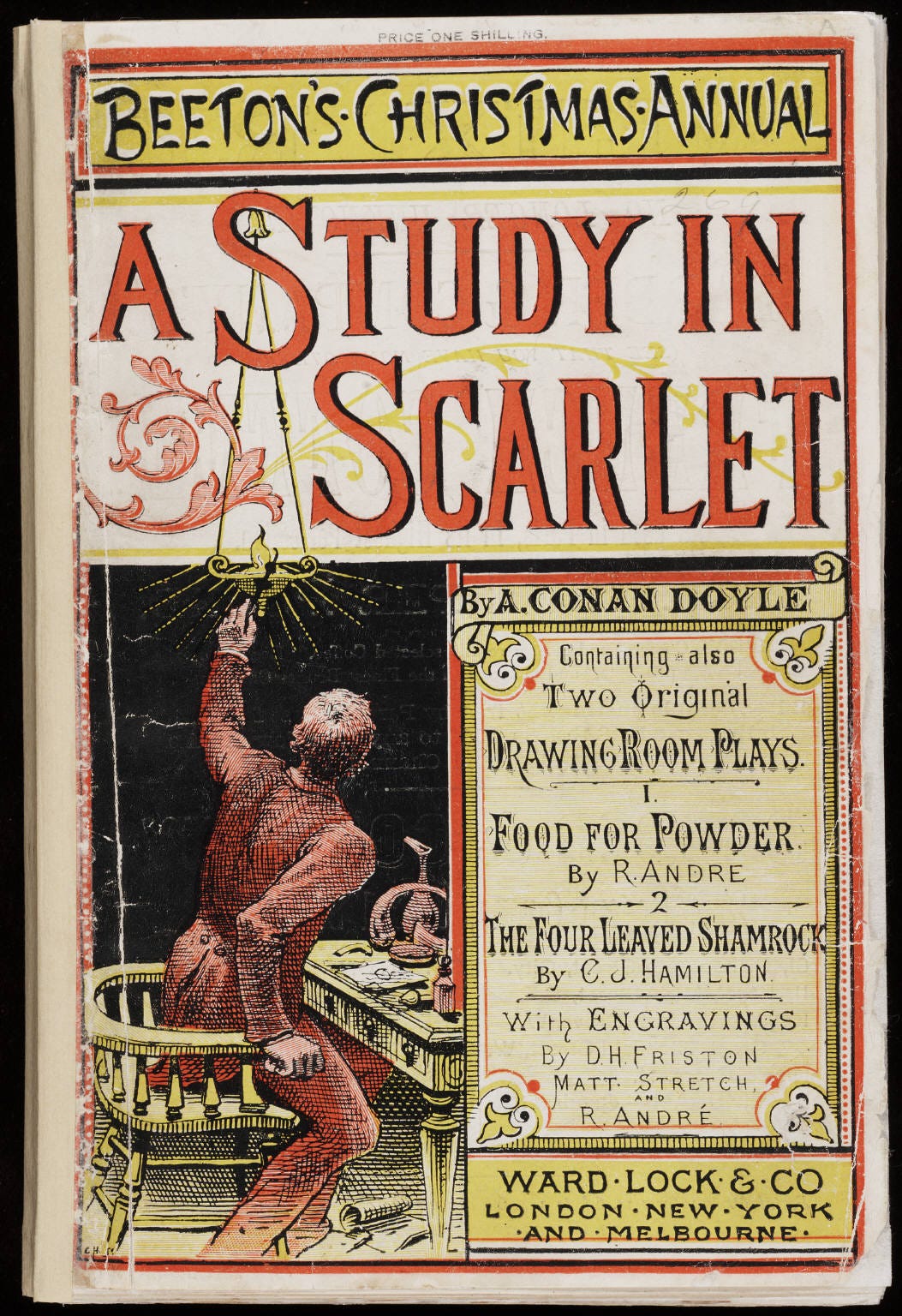

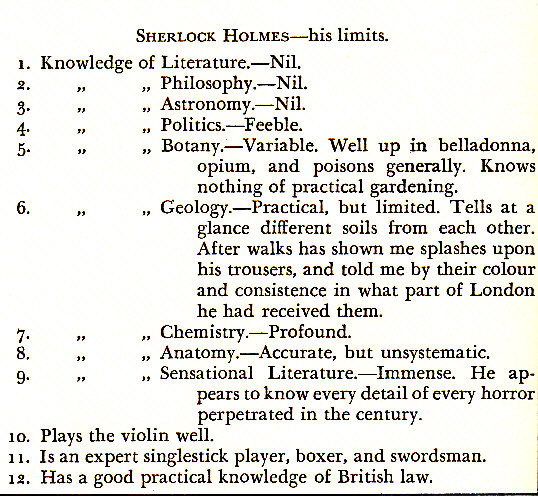

The first publication devoted to Sherlock Holmes, the novella A Study in Scarlet, originally appeared in the November 1887 periodical Beeton’s Christmas Annual. In the beginning chapters, Holmes’ chronicler, Dr. John Watson, meets the eccentric detective and agrees to share lodgings with him at 221B Baker Street in London. Soon after their first meeting, Watson, jots down a dozen of Holmes’ “limits.”

Of the first three – literature, philosophy, and astronomy – Holmes’ knowledge is “nil.” By No. 7, things things are picking up for Holmes: “Knowledge of Chemistry – Profound.” Of special interest to us is entry No.10: “Plays the violin well.” Upon completing the list, Watson followed with the world’s first description of Holmes’ style and technique: “I see that I have eluded above to his powers upon the violin. These were very remarkable, but as eccentric as all his other accomplishments. That he could play pieces, and difficult pieces, I knew well, because at my request he has played me some of Mendelssohn’s ‘Lieder’ and other favourites. When left to himself, however, he would seldom produce any music or attempt any recognizing air. Leaning back in his armchair of an evening, he would close his eyes and scrape carelessly at the fiddle which was thrown across his knee. Sometimes the chords were sonorous and melancholy. Occasionally they were fantastic and cheerful. Clearly they reflected the thoughts which possessed him, but whether the music aided those thoughts, or whether playing was simply the result of a whim or fancy, was more than I could determine. I might have rebelled against those exasperating solos had it not been that he usually terminated them by playing in quick succession a whole series of my favourite airs as a slight compensation for the trial upon my patience.” The “Lieder” refers to Felix Mendelssohn’s “Lider ohne Worte” – i.e., “Songs without Words.” Beginning in 1832, Mendelssohn composed eight volumes of these beautiful Romantic compositions, all for piano.

Dr. Watson returns to the theme of Sherlock Holmes, violinist, later in the novella, when Holmes tells Watson he looks tired and should go to bed: “I was certainly feeling very weary,” Watson reports, “so I followed his injunction. I left Holmes seated in front of the smoldering fire, and long into the watches of the night I heard the low, melancholy wailings of his violin, and knew that he was still pondering over the strange problem which he had set himself to unravel.”

In subsequent stories, readers learn that Sherlock Holmes occasionally experiences fits of melancholy, especially when he runs out of intellectual challenges. Sometimes he lifts his spirits by injecting a 9% solution of cocaine. More frequently, he augments his mood and accompanies his meditations by playing music. In “The Five Orange Pips,” published in The Strand in November 1891, Holmes is confronted with a problem involving orange seeds and the American Ku Klux Klan. Upon reaching a temporary impasse, Holmes tells Watson, “There is nothing more to be said or to be done tonight, so hand me over my violin and let us try to forget for half an hour the miserable weather and the still more miserable ways of our fellow-men.” At the end of “The Adventure of the Noble Bachelor,” published in April 1892, Holmes tells Watson, “Draw your chair up and hand me my violin, for the only problem we have still to solve is how to while away these bleak autumnal evenings.”

How skilled is Holmes’ violin playing? One of the final Sherlock Holmes stories, 1921’s “The Mazarin Stone,” provides a clue when Holmes leaves two criminals in his front room to confer in private. “Pray make yourself quite at home in my absence,” he tells them. “I shall try over the Hoffman ‘Barcarolle’ upon my violin. In five minutes I shall return for your final answer.” The narration continues, “Holmes withdrew, picking up his violin from the corner as he passed. A few moments later the long-drawn, wailing notes of that most haunting of tunes came faintly through the closed door of the bedroom.” But what they’re actually hearing is a recording. Homes manages to hide eavesdrop on their conversation and rescue the missing gem. As police race up the stairs, one of the culprits says, “But, I say, what about the bloomin’ fiddle? I hear it yet.” “Tut, tut!” Holmes answers. “You are perfectly right. Let it play! These modern gramophones are a remarkable invention.”

Sherlock’s Favorite Concerts

A Study in Scarlet contains the first of several mentions of Holmes’ love for classical concerts, nearly all of which feature real-life performers of the day. In A Study in Scarlet, it’s Austrian violinist Wilhelmine “Wilma” Norman-Neruda, popularly known as “the female Paganini.” During a lull in the action, Holmes informs Watson, “I want to go to Hallé’s concert to hear Norman-Neruda this afternoon. . . . Her attack and bowing are splendid. What’s that little thing of Chopin’s she plays so magnificently: Tra-la-la-lara-lira-lay.” Watson then describes, “Leaning back in the cab, this amateur bloodhound caroled away like a lark while I meditated on the many-sidedness of the human mind.” Watson is too tired to attend the concert, so upon Holmes’ return, the sleuth tells him, “It was magnificent. Do you remember what Darwin says about music? He claims that the power of producing and appreciating it existed among the human race long before the power of speech was arrived at. Perhaps that is why we are so subtly influenced by it. There are vague memories in our souls of those misty centuries when the world was in its childhood.”

The “Hallé’s concert” Holmes refers to is the annual Charles Hallé’s Popular Concerts series, which was launched in 1861 and ran in the late fall for nearly a half-century. A few months after the publication of A Study in Scarlet, the widowed Mme. Norman-Neruda married Charles Hallé and thereafter was known as Lady Hallé. At all of her concerts, she played the famous “Ernst Violin” created in 1709 by Antonio Stadivari. In a later story, it would be revealed that Holmes too played a Stradivarius.

Conan Doyle returned to the theme of Sherlock Holmes using classical concerts to help him sort out problems in the 1891 short story “The Red-Headed League.” Faced with a “three-pipe problem” (meaning this one’s going to take a while), Holmes tells Watson, “Sarasate plays at St. James’s Hall this afternoon. What do you think, Watson? Could your patients spare you for a few hours?” When Watson confirms that he can attend, Holmes responds, “Then put on your hat and come. I am going through the City first, and we can have some lunch on the way. I observe that there’s a good deal of German music on the programme, which is rather more to my taste than Italian or French. It is introspective, and I want to instrospect. Come along!” The remarkably named Pablo Martín Melitón de Sarasate y Navascués, a Spaniard, was a renowned violinist and composer who had, in fact, made his London debut in October 1890. Conan Doyle’s contemporary, playwright George Bernard Shaw, wrote that Sarasate’s compositions “left criticism gasping miles behind him.”

Watson’s detailed account of Holmes as Sarasate concertgoer offers insight into the master detective’s relationship with music: “My friend was an enthusiastic musician, being himself not only a very capable performer but a composer of no ordinary merit. All the afternoon he sat in the stalls wrapped in the most perfect happiness, gently waving his long, thin fingers in time to the music, while his gently smiling face and his languid, dreamy eyes were as unlike those of Holmes, the sleuth-hound, Holmes the relentless, keen-witted, ready-handed criminal agent, as it was possible to conceive. In his singular character the dual nature alternately asserted itself, and his extreme exactness and astuteness represented, as I have often thought, the reaction against the poetic and contemplative mood which occasionally predominated in him. The swing of his nature took him from extreme languor to devouring energy; and, as I knew well, he was never so truly formidable as when, for days on end, he had been lounging in his armchair amid his improvisations and his black-letter editions. Then it was that the lust of the chase would suddenly come upon him, and that his brilliant reasoning power would rise to the level of intuition, until those who were unacquainted with his methods would look askance at him as on a man whose knowledge was not that of other mortals. When I saw him that afternoon so enwrapped in the music at St. James’s Hall I felt that an evil time might be coming upon those whom he had set himself to hunt down.” Look out, bad guys!

Niccolò Paganini emerges as another of Holmes’ favorite performers in “The Adventure of the Cardboard Box,” first published in The Strand in January 1893. Let’s skip the part about the severed ears in the box and head straight to the musical references, as detailed by Dr. Watson. “We had a pleasant little meal together,” Watson chronicled, “during which Holmes would talk of nothing but violins, narrating with great exultation how he purchased his own Stradivarius, which was worth at least five hundred guineas, at a Jew broker’s in Tottenham Court Road for forty-five shillings. This led him to Paganini, and we sat for an hour over a bottle of claret while he told me anecdote after anecdote of that extraordinary man.”

The nineteenth century’s most celebrated violin virtuosi, Paganini was a supreme showboater. He coupled unsurpassed technique with dramatic flair, much to the delight of his audiences and consternation of his competition. He lived an extravagant “rock star” lifestyle, as we’d call it today, and likely suffered from Marfan syndrome, tuberculosis, depression, and syphilis, which he treated with opium and mercury. And, like Robert Johnson and others to follow, he was rumored to be associated with the devil. When Paganini passed away in 1840, the Catholic Church refused requests to bury him in consecrated ground.

Another Holmes concert reference occurs at the end of the 1901 novel The Hound of the Baskervilles, when Holmes reveals he has a box at the opera:. “And now, my dear Watson, we have had some weeks of severe work, and for one evening, I think, we may turn our thoughts into more pleasant channels. I have a box for ‘Les Huguenots.’ Have you heard the De Reszkes?” Real-life siblings, opera singers Jean, Edouard, and Josephine de Reszke hailed from Warsaw, Poland. A soprano, Josephine had quit performing in 1885, so Conan Doyle is presumably referring to brothers Jean, a tenor, and Edouard, who sang bass. The brothers starred at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City from 1891 through the early 1900s and apparently did appear together in productions of “Les Huguenots” in New York City and London.

Holmes’ enthusiasm for opera lasted well into the new century, as evidenced in the conclusion of 1911’s “The Adventure of the Red Circle.” Having just solved a mystery involving a frightened lodger and an Italian hitman, Holmes says to Watson, “By the way, it is not yet eight o’clock, and a Wagner night at Covent Garden! If we hurry, we might be in time for the second act.” Published in the mid 1920s and one of the last of Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories, “The Adventure of the Retired Colourman” contains the only reference I’m aware of to a performer who is likely fictional. Midway through the story, Holmes says, “Well, leave it there, Watson. Let us escape this weary workaday world by the side door of music. Carina sings to-night at the Albert Hall, and we still have time to dress, dine, and enjoy.”

Sherlock Holmes – Music Journalist?

In one of the later short stories, we learn of yet another facet of Sherlock Holmes’ love of music. In “The Adventure of the Bruce-Partington Plans,” published in The Strand, December 1908, Watson begins, “In the third week of November, in the year 1895, a dense yellow fog settled down upon London. From the Monday to the Thursday I doubt whether it was ever possible from our windows on Baker Street to see the loom of the opposite houses. The first day Holmes had spent in cross-indexing his huge book of references. The second and third had been patiently occupied upon a subject which he had recently made his hobby – the music of the Middle Ages.”

Then Holmes receives a missive from his brother Mycroft, summoning him to solve a murder and locate missing plans for an advanced submarine. The means he uses to achieve this fete, which involve “a jemmy, a dark lantern, a chisel, and a revolver,” are a good subject for an ethics class. Holmes prevails, naturally. The kingdom is saved, and the villain faces fifteen years in the slammer. “As to Holmes,” Watson describes at story’s end, “he returned refreshed to his monograph upon the Polyphonic Motets of Lassus, which has since been printed for private circulations, and is said by experts to be the last word on the subject.” A “motet” is a choral composition on a sacred text, and “polyphonic” indicates that it features several voices – in Lassus’ case, usually two to twelve.

A contemporary of Renaissance artists Michelangelo, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, and Titian, Orlande de Lassus was one of the most accomplished musical figures of the 1500s. He began his career in Italy, but spent most of his creative years in Munich. Among his 2000-plus compositions are more than 500 motets – some sublime, others more along the lines of Mozart’s “A Musical Joke.” Since they were written for voices rather than instruments, Holmes would presumably have had to sight-read them and imagine what they sounded like, so he had his work cut out for him. And just as Lassus was feted in his day by Emperor Maximillian II, France’s King Charles IX, and Pope Gregory XIII, Sherlock Holmes was honored by European royalty and various heads of state. Not that it mattered all that much to him – for Sherlock Holmes, it is always about the chase.

###

Thank you for supporting independent music journalism!

© 2022 Jas Obrecht. All right reserved.