Jimmy Rogers on Songwriting, Muddy Waters, and 1950s Chicago Blues

A Complete Transcription of Our 1996 Interview

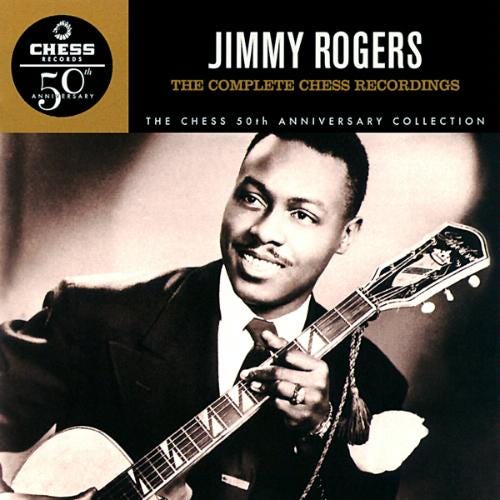

An under-sung hero of the blues, Jimmy Rogers played an essential role in creating the electrified, band-oriented postwar Chicago sound. He was best known for playing guitar in Muddy Waters’ lineups during the Chess Records era, but Rogers was also an accomplished solo artist and the composer of the blues classics “Walking By Myself,” “Ludella,” “Chicago Bound,” and “That’s All Right.”

He was born James A. Lane in Ruleville, Mississippi, on June 3, 1924. “One guy that my mother stayed around with was Henry Rogers,” he explained. “I grabbed his name when I became a professional musician, and began performing under the name.” His first instrument was harmonica. After living in Atlanta, Memphis, West Memphis, and St. Louis, Rogers moved to Chicago in the early 1940s. In 1945, he began associating with Muddy Waters, whom he coached on guitar. Rogers blew harmonica in their earliest lineup, while Muddy and Claude “Blue Smitty” Smith handled guitars. Eventually Baby Face Leroy Foster became their first drummer. When Smith departed, Rogers brought in teenage harmonica ace Little Walter Jacobs and began concentrating on guitar. In short order, this lineup became a cutting-edge Chicago blues band, rivaled only by Elmore James’ Broomdusters. “There were four of us,” Waters told Down Beat magazine, “and that’s when we began hitting heavy. Little Walter, Jimmy Rogers, and myself, we would go around looking for bands that were playing. We called ourselves ‘the Headhunters,’ ’cause we’d go in [to clubs] and if we got the chance we were gonna burn ’em.” As ferociously good as this lineup was, Leonard Chess did not initially allow them to record together.

Jimmy Rogers launched his recording career with Little Walter at his side, cutting the 1948 single “Little Store Blues” for the tiny Ora Nelle label. At his next session as a leader, in 1949, he cut his original version of “Ludella” with Muddy, Walter, and bassist Ernest “Big” Crawford. That year he also accompanied Muddy Waters as a sideman on “Screamin’ and Cryin’,” which initially came out on the Aristocrat label, soon renamed Chess Records. For the next half-decade, Rogers was a mainstay of the Waters band onstage and in the studio. That’s Jimmy playing first or second guitar on Muddy’s “Baby Please Don’t Go,” “I’m Your Hoochie Coochie Man,” “I Just Want to Make Love to You,” “I’m Ready,” “Trouble No More,” and “Got My Mojo Working.” Around late 1956, Jimmy departed the Waters band to go solo, but the two remained close friends.

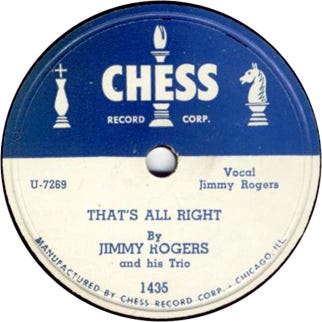

Beginning with 1950’s “That’s All Right” b/w “Ludella,” Jimmy Rogers’ Chess 78s rank right up there with Muddy’s as some of the finest examples of postwar Chicago blues. Among the highlights are 1950’s “Goin’ Away Blues,” 1954’s “Chicago Bound” and “Sloppy Drunk,” with backing by Muddy Waters and Willie Dixon, and 1956’s “Walking By Myself,” Rogers’ highest-charting record. With the advent of rock and roll, blues record sales diminished, and after a final Chess single in 1959, Rogers did not record again until the 1970s, when he cut the Gold-Tailed Bird album for Shelter Records. He rejoined Muddy Waters in 1978 for the I’m Ready album and tour. Rogers released several albums later in life, notably 1990’s Ludella and 1994’s Blue Bird. MCA/Chess released the two-CD Jimmy Rogers: Complete Chess Recordings in 1997, the year he died.

The following interview with Jimmy Rogers took place on August 28, 1996. At the time we spoke, he was living with his family on South Honore Street in Chicago.

***

I’d like to ask you about songwriting.

If it’s something that you want to do, you just concentrate on that. The way it starts is you get an idea, a punchline or something, and it sticks with you. It just goes with you. And then you put that little piece aside and get something else to match it, on and on. It takes a long time to write a good song. You can’t do it overnight, no.

Do you ever come up with the music before you have the right words?

Oh, you play by sound. You learn to play by sound before you learn to arrange or write. You gotta learn your axe, whatever it is – harmonica or guitar, piano, whatever you play. You gotta learn how to play the instrument first, and then after a while you have space there to start what you call writin’. Then you write, and then you gotta analyze what you’ve written and weigh it out, see if it makes sense. It’s a long-term situation.

Are most of your songs true-life stories?

Well, some of them was, and some I just visualized. You know, you don’t live everything that you hear or everything that you write about. Some of the things I’ve said I’ve experienced a lot – quite a bit of my life is the story, but not everything.

Like “Chicago Bound” . . .

Yeah, well, that song was put together from way back – Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, all around different places I’ve been. You put those pieces together as you go along, and eventually you fit it. It’s like a puzzle. It’s very, very complicated to write a meaningful song. That’s the way you do that. I just realized a lot of that stuff, and some I experienced, you know. So put that together and keep addin’ until you come up with something that’s important. Listen to people’s conversations – you listen to that, and see the reaction of people that you associate with, people that you become involved with, and all that stuff. It’s just a big puzzle there, but it’s very important. It was important to me enough to make me just forget about a lot of things that youngsters can run across. I wanted to arrange and write music, and that’s what I did, so it’s very, very, very important.

You go way back with recording. You even worked with Big Crawford.

Oh, yeah. I worked with Big Crawford.

What kind of guy was he?

He was a nice guy. He big and tall – big, tall guy. He weighed about 300-and-some pounds, and he stood about 6 '5" or something like that. He was a big, huge guy, like Willie Dixon. And I think Crawford was a little taller than Dixon was. He was very tall – big guy, man.

Was he soft-spoken?

Yeah, he talked normal. I’d see him all the time, and we would talk, crack jokes and fool around together. And man, we was concentrating on arranging. We were all doin’ the same thing together. Muddy, Walter. Me and Muddy would be there arranging. That’s where we got Walter into arranging songs like Muddy and I would do it. I would explain to Muddy – we’d see each other every day. It was just something I wanted to do. If I get an idea about some lyrics or something, I’d put them together by myself. You have to be by yourself, mostly. And when you get it kind of halfway lined up like you want to, then you would consult with your partner about it and you work on it.

Would Muddy bring you some of the songs he was working on?

Yeah. Well, I would do the same thing.

Would you more or less be finished with the song before you’d show it to the other guys?

We deal with it with just the two of us. I mean, Walter would be there, but he wouldn’t say anything. He just be listening and be there, and we’d be sittin’ down. He wasn’t much of a songwriter, Walter wasn’t, but he was a good player. But he would just be there. He wouldn’t interfere with us. He might get up and walk out or something, and go on wherever he had in mind to go, and we would still be doing this, working on arranging this stuff. That’s what we would do all the time. Every day we would do that – just about every day.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Talking Guitar ★ Jas Obrecht's Music Magazine to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.