Jesse Ed Davis: “Playing a Guitar Solo Is Like Never Never Land For Me”

A Celebration of the Life and Recordings of a “Guitarist’s Guitarist”

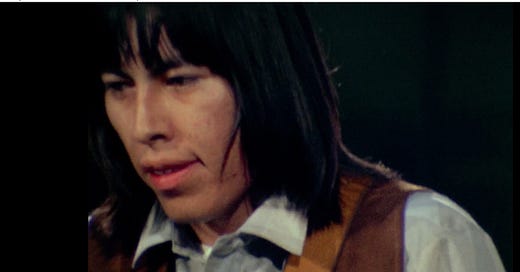

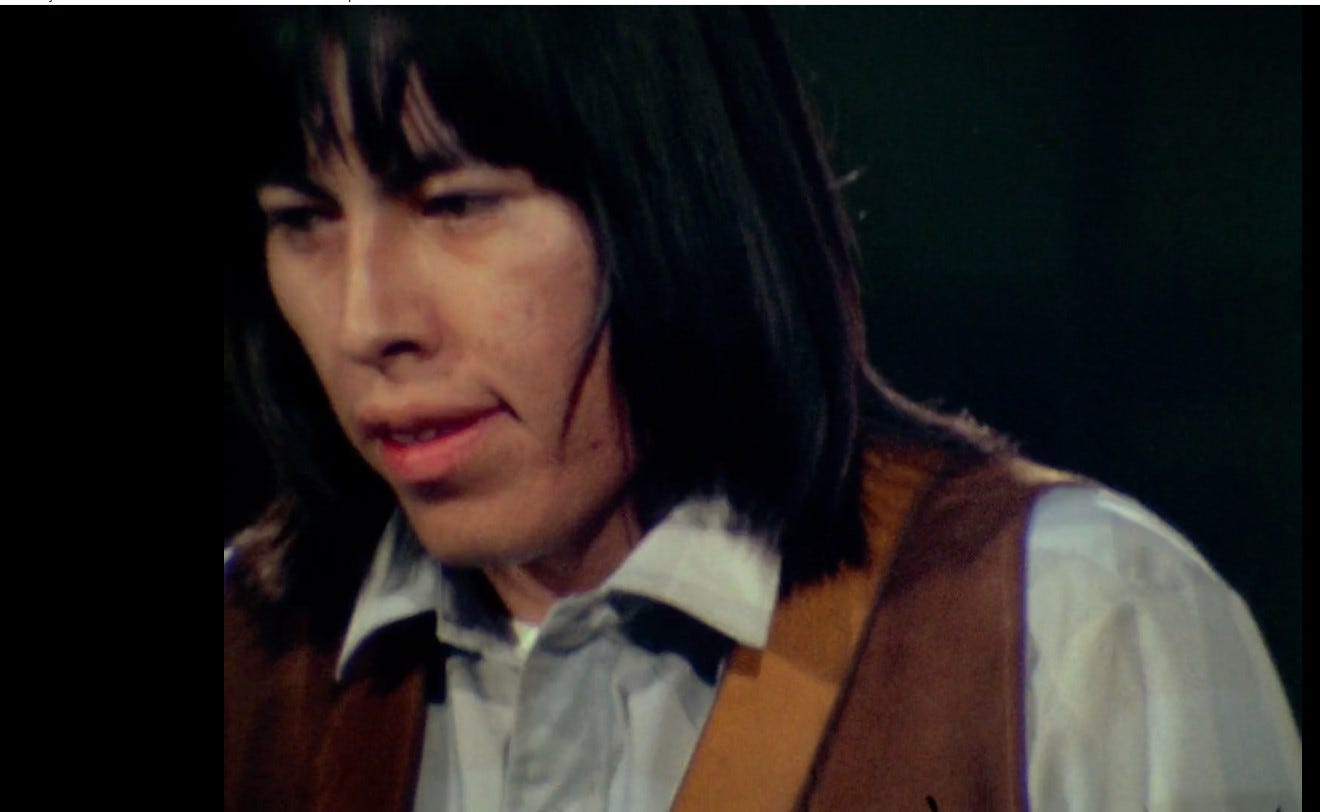

Charismatic Jesse Ed Davis was truly one of the rare breed known as a “guitarist’s guitarist.” With his handsome features, long black hair, and mod clothes, Davis cut a dashing figure onstage. He was one of few Indigenous Americans to achieve prominence in pop music during the late 1960s and 1970s. On session after session, he epitomized the concept of “playing for the song,” drawing deeply from country, blues, rock, and R&B influences without mimicking anyone. He recorded with three of the Beatles and blues giants John Lee Hooker, B.B. King, Lightnin’ Hopkins, and Albert King. He appeared in the film Concert for Bangladesh and played sessions with Eric Clapton, Gene Clark, Neil Diamond, John Trudell, and many others. He released three solo albums on major labels. And yet despite these accomplishments, Jesse Ed Davis remains best known for his work on the early Taj Mahal albums and for being “the guy who inspired Duane Allman to play slide guitar.”

True, Jesse created the signature riff used by Duane for the Allman Brothers Band’s “Statesboro Blues” and played the bottleneck on Eric Clapton’s “Hello Old Friend.” But slide was just one facet of Davis’s widespread talent. Playing fingers-and-pick country on his trademark Telecaster, he could fire off multiple-string bends and double-stops as naturally as a Nashville cat. In blues settings, he made every note count, like a B.B. King or Mike Bloomfield. He delved into jazz. He created memorable hooks. His uncanny feel for rock led to his becoming John Lennon’s guitarist of choice for the Rock ’n’ Roll album.

A citizen of the Comanche Nation, Jesse Edwin Davis III was born on September 21, 1944, in Norman, Oklahoma. He grew up on a reservation, where hearing the records of two artists sparked his interest in the guitar: “Jimmy Reed and Elvis Presley came along,” he told B. Mitchell Reed in a 1973 radio interview. “That really did it for me. We had an old guitar laying around. It was a Stella guitar, one of the 1095 models. I used to tie a rope around it and put it on my shoulder and stand in front of the mirror and watch myself mimic Jimmy Reed records and stuff.”

None of his childhood friends, Davis added, shared his childhood interest in music: “I really had to go it alone for a while. All my friends thought I was weird for getting into that. Well, I was always a little weird anyway, being an Indian in Oklahoma. Oklahoma is kind of like a six-gun city, you know. It’s still the Wild West back there. It’s really provincial. Since I’ve grown up, I really look back and see a lot of the racial things I went through that were really heavy, formative trips in my life.

“One of the songs on my Keep Me Comin’ album is about an incident in the third grade, ‘Ching, Ching, China Boy.’ These two guys used to follow me around – I guess I looked Chinese to them – and they’d follow me around and sing at me and taunt me with their little song. Finally they cornered me one day and said, ‘Well, if you don’t start swinging, you’d better duck.’ So I started swinging – a big roundhouse right. He could really see it coming for a mile. He didn’t duck or anything. It landed squarely on his nose and he fell down and the other guy ran away. That was the end of ‘Ching, Ching, China Boy.’”

Davis began playing seriously while in seventh grade, when his father bought him a Silvertone electric guitar at Sears & Roebuck. “I used to just sit for hours and figure themes out,” he recalled. “I had that Silvertone for a long time until I finally just wore it out. All this time, I had my eye on a Fender Telecaster that had been sitting around in this same store for years and years. It was brand-new, but nobody ever bought it. When I was about 16, my dad finally gave me that Telecaster, which I’ve played for many years. The guitar just struck a hidden chord deep within my soul.” He credited a local blues pianist, Wallace Thompson, for teaching him how to play blues, and performed in a high school rock band with Michael Brewer, later of Brewer & Shipley.

Around 1960, Jesse launches his musical career: “When I was about 16,” he told Reed, “I took off on the road with Conway Twitty. My first gig with him was a 30-night Dick Clark tour. It was a bus tour, and one of Conway’s biggest friends – I think they’re from the same part of Arkansas – was Ronnie Hawkins. And at the time he had The Band – Levon Helm and the Hawks – backing him up.” Jesse gained his first studio experience playing on singles by Jr. Markham & The Tulsa Review, for the obscure Uptown label. “After that,” he recalled, “I was just laying around playing with nobody for three years, until I started playing with Taj.”

In 1964 Jesse quit college, where he was studying English literature, and moved to Los Angeles. “When I quit college and came out here,” he told Reed, “Levon had a brief vacation from The Band. He came out here to Los Angeles, and he was the only guy I knew here in L.A. I gave Levon a call, and he said, ‘Come on over. There’s a guy you really gotta meet.’ And it was Leon Russell, who was really into his sessions back at the time. When I first met Leon Russell, he didn’t have long hair. He had an Elvis Presley pompadour – a D.A., right? He was, I guess, one of the top session pianists in town. He played with Frank Sinatra, did arrangements for Johnny Mathis, and all that routine. It really opened my eyes. My eyes got really big. I couldn’t believe it. So we started hanging out. I just drifted into that whole scene. Leon got me my first session with Gary Lewis. From there it just kind of mushroomed out. People started hearing about me. I think record producers are always anxious for new blood. Pretty soon they get tired of the same guy’s licks and they bring a new guy in.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Talking Guitar ★ Jas Obrecht's Music Magazine to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.