Homesick James Remembers His Pal, Elmore James

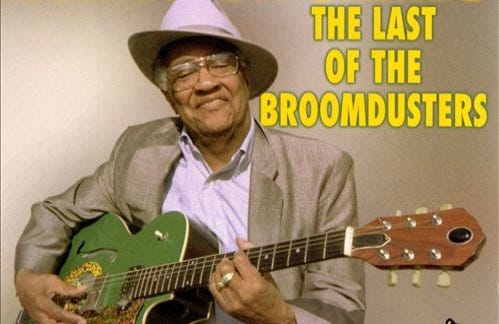

The Complete 1993 Interview With the Last of the Broomdusters

For decades after Elmore James’s death, his boyhood friend and Broomdusters bandmate Homesick James was one of the leading advocates of his music. Homesick’s throaty, bittersweet sliding regularly conjured images of Elmore and his Broomdusters “rollin’ and tumblin’,” as they used to say, in sweaty Chicago taverns. Homesick’s distinctive tone was a combination of heart and hands, a hunk of conduit pipe, a homemade guitar, and a battered amp. Performing into his eighties, he sang with a vibrant, vibrato-drenched voice somewhat reminiscent of the second Sonny Boy Williamson’s.

Blues references list Homesick’s name as “James Williamson,” although during our meeting he stated, “I can’t tell nobody what my real name is. I never uses it. But my passport says John William Henderson.” He was born in Longtown in Fayette County, Tennessee, on April 30, 1910. His father, a cotton worker named Ples Rivers, played snare in a fife and drum band, and his mother, Cordelia Henderson, performed spirituals on guitar. His church-going mother forbade him to play, fearing he’d learn blues songs, but by age eight the youngster was hauling out her guitar on the sly.

A neighbor named Tommy Johnson—not the famous one who made 78s—taught him to play lap-style slide with a pocketknife. Young Homesick met Blind Boy Fuller during a visit to North Carolina. Mississippi sojourns brought him his first contacts with Howlin’ Wolf, Johnny Shines, and Elmore James. Homesick James and John Lee Williamson (a.k.a. Sonny Boy Williamson I) also met as boys and may have been related.

By 1933, Homesick, Sonny Boy, Yank Rachell, and Sleepy John Estes were working the southwest Tennessee blues circuit, with regular stops in Jackson, Brownsville, Nutbush, Mason, and Somerville. Homesick moved to Chicago in ’34 and stayed with Sonny Boy, who’d arrived months before, until he found work at a steel mill. At night he played covers of Memphis Minnie and Blind Boy Fuller songs with Horace Henderson’s group at the Circle Inn. He was quick to electrify his sound; a photo of him at the Square Deal Club, his second extended booking in Chicago, shows him playing a Gibson ES-150, which had just been introduced in 1936.

On occasion Homesick journeyed south to play with Yank Rachell, Sleepy John Estes, and Little Buddy Doyle. (James claims that he was one of the uncredited musicians who played on Doyle’s 1939 Vocalion sides.) After serving in World War II, Homesick joined Sonny Boy, Big Bill, and pianist Lazy Bill Lucas at Chicago’s Purple Cat, with harmonica ace Snooky Pryor sitting in whenever he could get a pass from nearby Fort Sheridan. Later on, Homesick and Snooky worked with Baby Face Leroy Foster in South Chicago. Called up from reserve status, Homesick was wounded during a Korean tour of duty.

Homesick made his first recordings under his own name during 1952. Cutting for Chance Records at the old RCA Victor studio on South Michigan in Chicago, he dialed in a thick, distorted tone and traveled downhome, humming and moaning “Lonesome Ole Train” to Lazy Bill’s rocking barrelhouse piano. With lines like “I ain’t gonna chop no more cotton, I ain’t gonna plow no more corn,” the flip-side’s “Farmer’s Blues” was aimed at ex-sharecroppers who’d migrated to the North. Homesick claimed that his second Chance session, with Snooky Pryor, was unissued.

His next Chance session produced the hit “Homesick,” a rollicking romp with Robert Johnson-style turnarounds and slide figures that reappear on Elmore’s later recordings. Its B side, “The Woman I Love,” rocked to the “Baby Please Don’t Go” melody and featured Johnny Shines on second guitar. At subsequent ’50s sessions, Homesick backed Lazy Bill on a Chance 78 and covered Memphis Minnie’s “Please Set a Date” for Colt. He assumed the pseudonym “Jick and His Trio” for a 78 on the short-lived Atomic H label.

In 1957 Homesick James began recording as part of Elmore James & His Broomdusters. Usually playing bass parts on a tuned-down electric guitar, he’d perform on dozens of essential recordings during the ensuing three years. Among the gems were “The Twelve Year Old Boy” and “It Hurts Me Too” on the Chief label; “The Sky Is Crying,” “Dust My Broom,” and “Baby Please Set a Date” on Fire; and “The Sun Is Shining,” “Stormy Monday Blues,” and “Madison Blues” on Chess. In 1960 the band journeyed to New York City to tape “Rollin’ and Tumblin’,” “Done Somebody Wrong,” “Standing at the Crossroads,” and other songs for the Fire/Fury.

While Homesick did not participate in Elmore’s few remaining sessions, they continued to play together onstage. Their performances were a sight to behold! As Robert Palmer pointed out in his liner notes for The Sky Is Crying, “The Broomdusters were one of the greatest electric blues bands. In terms of creating a distinctive and widely influential ensemble—and in terms of sheer longevity—the Broomdusters’ only real rival was the Muddy Waters group that included Jimmy Rogers, Little Walter, and Otis Spann. And judging from the recorded evidence, the peaks of intensity reached by the Waters band in full cry were at a level the Broomdusters reached before they’d finished warming up.”

On May 24, 1963, Elmore James died of a heart attack in Homesick’s apartment. For a while, Homesick fronted his own group in the same South Side taverns where he’d begun. In 1964 he recorded an album for Prestige, Blues on the Southside. Homesick James & His Dusters (bassist Willie Dixon and drummer Frank Kirkland) resurrected Elmore’s spirit on the 1965 Vanguard anthology Chicago/The Blues/Today!, covering “Dust My Broom” and “Set a Date.”

During the ’70s Homesick played clubs and made forays into Europe, often in partnership with Snooky Pryor. Their 1973 American Blues Legends tours of Europe produced a pair of albums and a review in which a critic described James’ “usual tricks—playing guitar behind his back, jumping up and down, laying on the ground while playing.” At the time, Homesick was in his early sixties. James went on to record for Bluesway, Caroline, Black & Blue, and other small labels. (Here’s a link to Stefan Wirz’s excellent annotated discography: Homesick James.)

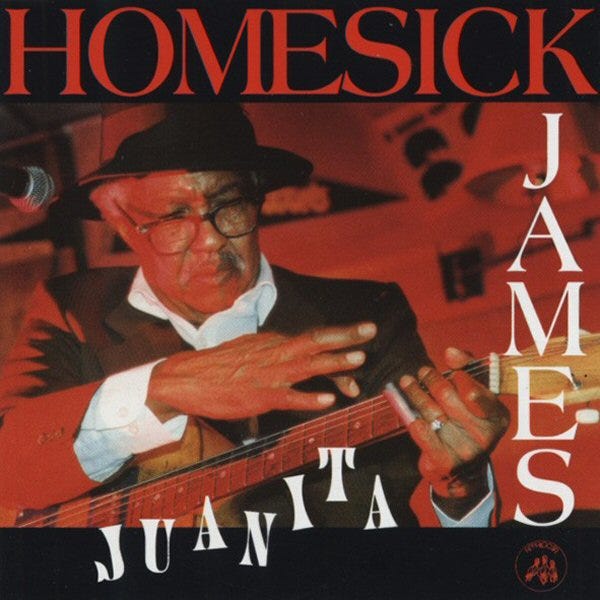

During the 1990s Homesick James held court as one of the elder statesmen of Chicago blues, making appearances at blues and jazz festivals and recording several albums. He also built electric guitars, drank heavily, and claimed credit for some of Elmore James’s accomplishments. Our interview took place during the summer of 1993, when Homesick was living in Nashville and had just recorded his Juanita LP. He passed away at his home in Springfield, Missouri, on December 13, 2006.

###

Who are the best musicians you’ve worked with?

I’ll tell you, the best I worked with was me and Elmore. See, I was Elmore’s teacher. And when he passed away, he passed away on my bed. Oh, yeah, he died right there in Chicago at 1503 North Wieland Avenue. He just had come back, and he said that when he died, he was gonna die with me. I wasn’t thinkin’ nothin’ of it. And about two weeks later, he was gone. He was stayin’ with me. That was 1963, May the 23rd or 24th. We was gettin’ ready to go to a gig too—Club Copa Cabana.

Elmore sure was a fine slide player.

Well . . . [Laughs.] He got all that stuff from the old master here.

From you?

Hell, yes! I give him his first guitar when he was about 12 years old. I knowed where he stayed in Mississippi. I worked down there. Him and a guy by the name of Boyd Gilmore was tryin’ to play. Elmore had a piece of wire tied up on a coffee can and a board—it had one string on it. He was tryin’ to learn so hard, but Boyd Gilmore, he had an old guitar.

People have speculated whether Elmore James knew Robert Johnson.

Yep. Sure, Elmore knowed Robert Johnson. Well, Elmore and all of them were down in the Delta together. Elmore and Rice Miller, who was Sonny Boy number two—all those guys, they know Robert. I met him. See, I knowed Robert very well. Robert Jr. Lockwood can tell you that. I also knowed another guy that nobody never said anything about—I knowed Charley Patton personally. Now, I ain’t thinkin’ that I know them, I know these people. I know Ishman Brady [Bracey] perfect. We would associate around together. When I used to come through there, that’s what would be playing at the picnics and the barrelhouses and things. I was hoboin’ with my guitar, a Stella 6-string.

Were these tough men?

No, no. Nope. They would just drink and gamble, that’s all. They run ’round with women and drink and gamble. That’s what musicians act. No, they wasn’t no mean guys. All of us was drinkers. Every musician drink. Ain’t but one time he’ll stop—that’s when he comes down diabetic. Yeah, then they’ll quit because they have to.

Describe your first gigs.

I played many a country supper. I was out runnin’ around—picnics and frolics like that, me and Yank Rachell, Sleepy John Estes, and Little Buddy Doyle. We’d play at a picnic right here outside of Oakland, Tennessee, out on Highway 647. Little Buddy Doyle was a midget and I knew him personally, because me and him recorded together. That’s sure the truth. Yeah. It was in 1937. Big Walter Horton was on the harmonica. It was at the Hotel Gillsaw in Memphis, right across the street from the Peabody Hotel. It was wire recording machines.

But that wasn’t really the first song I ever did. I did some stuff back in ’29, a song with Victoria Spivey. She’s the first person that turned me on to studio stuff. See, I did “Driving Dog” in 1929. [Ed. Note: This title does not appear in discographies.] Victoria Spivey, she heard me play, and she said I played that “cryin’ guitar.” Elmore, now he had never started yet. See, I had been with the Broomdusters ever since 1937 myself. I had the Dusters.

The expression “dust my broom” means to get out of town in a hurry, right?

Uh, no. It never was “dust my broom.” It was “dust my room.” And people made a lot of mistakes by sayin’ that.

A lot of people heard Robert Johnson’s version, which was “dust my broom.”

“Dust my room,” that’s what it was. That was around before Robert Johnson did it. That was around in the ’20s—’29 or ’30. [For a full rundown on this song’s lineage, see my post “Dust My Broom”: The Story of a Song.”]

How did you and Elmore get back together in Chicago?

What happened, he had an uncle there named Mac. And Elmore had this one record out, and this was that “Dust My Broom” thing with Rice Miller. He didn’t have but one side [of the Trumpet 78]. He didn’t do the other side, that “Catfish.” Another guy down in Mississippi [Bobo Thomas] did that. Elmore just had one riff on guitar.

See, I can read music and write it too. And what happened, I sent Elmore a ticket to get him to Chicago, because he had this song out that was so popular. Me and Snooky Pryor were workin’ together out of the south of Chicago in the Rainbow Lounge, and when Elmore come, I had to quit and go and get Elmore together, because he didn’t have nobody.

On some nights, it’s said, you and Elmore were so hot that people threw money at your feet.

Oh, yeah. Heck yeah! Aw, people just give us money, man. When we played, people just come in and throw a twenty or a ten—that’s the way it was. We were pretty good musicians, though.

How did you end up playing bass with Elmore?

I always could play bass. Harmonica, bass, guitar—I can play any instrument. But that wasn’t no bass with Elmore. That was guitar tuned low. Elmore played bass too. We had a way of playing these guitars that no man would be able to do these things. In the key of D, I would keep four strings tuned into that Vastapol [D, F#, A, D, from the D string to the high E], and we would run those other two strings, the A and E, down lower, just like a bass, so it sounds like a bass.

A lot of time when we’d be playin’, Elmore would be runnin’ that bass like I did while I be runnin’ slide. See, all he would do is [sings the “Dust My Broom” riff] and run back to the bass pattern. All he could do was go to D. But he wasn’t able to go to G and A in the D tuning. I’d let him play his part when it got to it, and I’d catch those other chords.

We was workin’ so good together. We were just a team. He’d run that real high note and then jump to the bass, and I’d jump right there. You couldn’t tell when one switched to the other. See, we studied this stuff together, how to come up with ideas. We was the hottest band in Chicago. That’s the way we were.

Were you playing loud?

No, no. Never did it loud. I don’t allow it now.

Would people be dancing?

Oh, man. That’s all they did, was dance. Yeah. Those days were so sweet, man. Everybody come out to drink, dance, and have a good time. Yep.

Did you do much touring outside of Chicago?

We come down to Atlanta, Georgia. We had a station wagon from Chess Records. I’d taken my money and put half, and he’d taken his money and made the payment. We traveled to a country club in Georgia. We played around there, and then we played around Cleveland, Ohio.

Was Elmore pretty quiet offstage?

Well, Elmore was real quiet all the time—until he take a drink. He used to say, “I’m Elmore. After me there won’t be no more.”

What did he like to do besides music?

Me and him used to set around and tinker with electricity and mess with making guitar stuff. If we wasn’t makin’ them, I’d be putting them together for him. Did you see that big old Kay guitar he got? I fixed that. I wired it up. He bought that guitar, paid $20 for it at a pawnshop over on Madison Street. It wasn’t no electric. He said, “Will you put some electricity on it?” I said, “Yeah.” I always knowed about electric.

Me and him used to sit together. He stayed at my house all the time. I used to live on 1503 North Wieland, and I used to live at 1407 Northwestern. This was in ’59, when we did “The Sky Is Crying,” “Bobby’s Rock,” and all this stuff. And that’s where I built his guitar for him.

Bobby Robinson writes that Elmore composed “The Sky Is Crying” the night before the session.

Ah, no. No, no. I know direct, ’cause I was right there. Okay. That’s my song. That don’t belong to Bobby Robinson or none of ’em. See, it had been rainin’ so hard, and we were sittin’ alone at 336 South Leavitt in Chicago. See, me and Elmore came up with the idea “The Sky Is Crying,” but I told him, “Don’t say that. Say ‘the cloud is cryin’,’ because the sky don’t know how to cry. The rain come out of the cloud.” And when he got in the studio, he forgot. When we got home, he said, “You know, I made a mistake. But it’s good, wasn’t it?” I said, “Yeah.”

But no, he didn’t write that. “The Sky Is Crying” come out in ’59, and then we did “The Sun Is Shining,” the “Madison Blues”—all that stuff is mine. I can verify these statements. Ask Gene Goodman at ARC Music—that’s the copyright on all those songs. Later on I made “The Cloud Is Crying” for the Prestige label.

Which is the best label you worked for?

Vanguard wasn’t too bad.

Besides Elmore’s, what are the best records you’ve played on?

I’ll tell you, the best thing I ever did was “I Got to Move,” number one. I love that tune. Oh, yeah. I did that for Columbia or Decca, a long way back. I like that, and I like “Set a Date,” ’cause all the youngsters are doing it now, like Fleetwood Mac, George Thorogood. After I had did it, then Elmore did it. He asked me if it was all right. See, Elmore wasn’t no writer.

If, as you say, Elmore was taking credit for songs you wrote, didn’t that cause trouble between you?

Well, how? No. We had an agreement, man. Noooo. See, every time he would ask me did I have some songs, you know. He say, “Can I do any of your songs?” I said, “Look. You don’t have to ask me. Let’s do it.” Didn’t make no difference. Some people, you tell ’em one thing, they’ll print another. I seen a lot of things that they said about Elmore, and I said, “No, no, no, no, no. This ain’t right.”

Like when I come up with the “Madison Blues,” I played it all up and down Madison Street. That’s where I wrote that song. See, we worked on a partnership basis. Like if he were living today, whatever royalty come, we broke it right down. He never was paid no more on a job than I was. Me and him got the same salary. But now the sidemen didn’t get what we get. See, that was the agreement with the owners. “Homesick was makin’ records way before I was,” Elmore would tell them. He said, “Now, you ain’t willin’ to pay two leaders, I won’t be there.” I would tell them the same thing. That’s the way we worked it. We just shared together.

You must have been really close.

Tell me about it. I never have been that close to nobody, no musician, because we just stayed together. Me and him run into a lot of problems, but we never had a argument. We had problems with our station wagon one time. That was up in Cleveland, Ohio. They repossessed it; they come and got it. Yeah. We got stranded.

See, what was happenin’, we had an agreement: “I pay this month, you pay next month.” So his month come, he told me he had paid, and he didn’t. When my month come, I sent my payment in. He got way behind on his, because he loved to play cards. He loved to gamble—drink and gamble. He’d lost all his money. He was always calling me and asking me to give him money, and I’d give it to him. I didn’t loan it to him, I just give it to him. I’d say, “Yeah, what you want?” We were just like that.

They come and got the wagon. We was playing at a Cleveland musical bar, and we went out, and he told me somebody else stole it. He wouldn’t tell me the facts about it. I called the guy who was booking us, Bill Hill, and asked him. He said, “Didn’t you see Ralph Bass?” ’Cause Ralph—you know, the engineer for Chess Records—and Philip Chess, they come in the same night. I thought they was comin’ through from New York, but they come there to get that wagon. It was a 1960 Ford Catalina, nice station wagon. It had “Broomdusters” on the side of it.

Anyway, then we had to get a ride back. So what’d we do? Now, Elmore had a contract with Chess Records. He said, “I’m gonna call Bobby Robinson, and I’ll see can we get a session.” Bobby agreed with it, and we flew in from Cleveland, Ohio, to New York, and that’s where we recorded that “Rollin’ and Tumblin’” and all those other tunes. That was in 1960. And we take all our money, put it together, and bought another wagon while we were up there. Same model, but it was rust-colored or beige. The first one was solid white. We had chauffeurs to drive us. We wouldn’t drive ’cause we be drinkin’ too much, carryin’ on, talkin’. Me and Elmore, we were just always together, man.

What was your favorite drink?

Scotch. We’d drink that, and then we’d drink Kentucky Tideman or anything we could get to get high off [laughs]. We’d just sit back and come up with ideas and talk it, how we want this played. I was the leader of that band. Oh, yeah. That was my band all the way. We had J.T. Brown on the horn, Boyd Atkins. That was the best band I ever have worked with. J.T. was good about arrangin’ music too. All those guys is dead now.

What did you use for slides?

Before I started making them from conduit pipe, I used the metal slip that goes over the top of tubes in them old radios and old record players. I used to pull that out and put it on my finger and play. This was after I learned how to stand it up [hold the guitar in normal playing position].

What did Elmore use for slide?

The same thing. A tube cover. Elmore used a light piece of metal, and Elmore had some big fingers too. He’d take one of those slips—protector tubes—from an old amplifier and put it on his finger. If he got a smaller one, then he would split it open—take a hacksaw and saw it open. That’s what we played with all the time. See, we used to mess with a lot of stuff. But I use that conduit pipe all the time now. I don’t like heavy. I don’t think no man should use them big old heavy slides. You can’t. The sound ain’t there. Like you go to a store and buy them—whew, that’s too much weight on your hand.

What amplifier did Elmore use at the Fire session in Chicago?

Mine. A Gibson. A big one. A GA-53, I think it was. It’s at my house in Flint, Michigan, in the basement. I own a little small farm up there, and a lot of my kids live there. I got it when I was in the Army. The amp is brown on top and gray tweed at the bottom. It had letters on it, but by travelin’, someone done knocked them off. It’s about two-and-a-half feet high, and it could fit one 10 and one 12 speaker in the cabinet. Elmore didn’t have no amplifier, and he didn’t have no good guitar.

So to the best of your knowledge, that’s the amp “The Sky Is Crying” was cut on?

I know what it was cut on, sure! Yeah, that’s what it was cut on. And I got the picture with Elmore standin’ with the guitar with my amp right there. Everywhere I go I keep it, so somebody start to try to say something about Elmore, I just straighten them up right quick.

Okay, I want to tell you this too: That was a studio sound that people try to figure out. They’ll never get that. The people at the studio knew how to operate that stereo sound into it. That’s what that is. That’s an echo sound. And it’s two slide players—that’s me and him both.

Were you in a big room?

No, not too big. Small studio. Bob Robinson come down and produced that for Fire and Fury Records. Yeah.

Beautiful sound. Open tuning.

The only people I really know who played in open D was me and Elmore. He had it in open D when he made “Dust My Broom,” because Sonny Boy was playing a G harmonica. I always told him, “Don’t never tune that string up too high,” because if you tune that thing up to open E, you got too much pressure on your guitar neck. So you just let the strings back down.

See, I can’t play a guitar like a lot of peoples could do—I just don’t like that sound. Elmore never did like that either. I always keep a mellow sound. Don’t never press down on your strings too hard. Just glide the slide. Take your time slidin’, and don’t be mashin’ down on ’em. See, some people play the strings too high. The slide guitar players, they got to jack the strings up ’cause they always mashin’ down, and the slide hit the frets. But my guitar strings are right down on the neck. Muddy had a heavy touch, and Hound Dog Taylor. The sound was brighter; it ain’t no mellow sound, man.

What’s your favorite electric guitar?

I make my guitars. I build my own guitars and fix them the way I want. But my favorite parts for what’s goin’ inside the guitar are Gibson. My favorite sound is Gibson. I bought some of those Seymour Duncan pickups, said I was gonna try them, and I don’t like ’em. Too bright.

I make acoustic guitars—the big ones with f-holes—and then I put electric to it. And then I buy the pickups and the controls and whatever I need—the switches—and put ’em in there. My house is a workshop. I got guitars all over the place. I make ’em, builds ’em. I can go out and see a nice piece of wood, and I’ll just take it and make me a solidbody. I ain’t made acoustics since I been here in Nashville because I ain’t got my blocks what I make ’em out of. But they sound better to me than the ones I could buy.

What was your setup on the new record?

I made the guitar I was usin’. You never seen a guitar like that. Everybody wonder how I put it together like that. It got a paint job on it, it got a lot of designs all over it. That was a Twin Reverb amplifier. Yeah, but give me the Gibson.

Some players say that a smaller amp gets a better sound for slide, makes it sound more like a harmonica.

Aw, no. It don’t have to be. It depend on the way you set it.

Do you use guitar picks?

No, I play with my hands. I never have in my whole life used no pick. You can’t slide like that, no. Nobody will ever be able to get the sound what I get out of the guitar, because I’m usin’ my fingers. I wear the slide on my little finger, and I be pickin’ the slide too at the same time I’m making chords with my other fingers.

You’ve been playing music for 70 years . . .

Over!

What’s your secret for longevity in the business?

My advice for all youngsters is have a nice personality—number one. Know how to treat people, and don’t let nothing go to your head, because those people, they the ones buyin’ your material. They the ones that helped you up the ladder. Just work with the audience, and don’t never insult nobody. Be a gentleman about things. And don’t hang out all night if you can keep from it. Always try to go home and get you some rest. That’s what I do, and I don’t age that much. I take it easy, and when I’m not playin’, you’ll find me right at home.

Thanks for the interview.

Oh, I’m glad to help out. Anybody want me to help out in any way or anybody ask me something, I’m not too proud to do it. I don’t like to copy nobody. Everywhere I go, I leave a ball of fire.

###

Related posts:

“Dust My Broom”: The Story of a Song

Elmore James: “Dust My Broom” on Trumpet Records

Robert Johnson’s Best Day in the Studio

Help wanted! Each Talking Guitar post and podcast requires a lot of work. If you’re not already a paid subscriber, please become one now or hit the donate button to make a one-time contribution. For $5 a month or $40 a year, paid subscribers have complete access to all of the 180+ articles and podcasts posted in Talking Guitar. Thank you!

© 2024 Jas Obrecht. All right reserved.