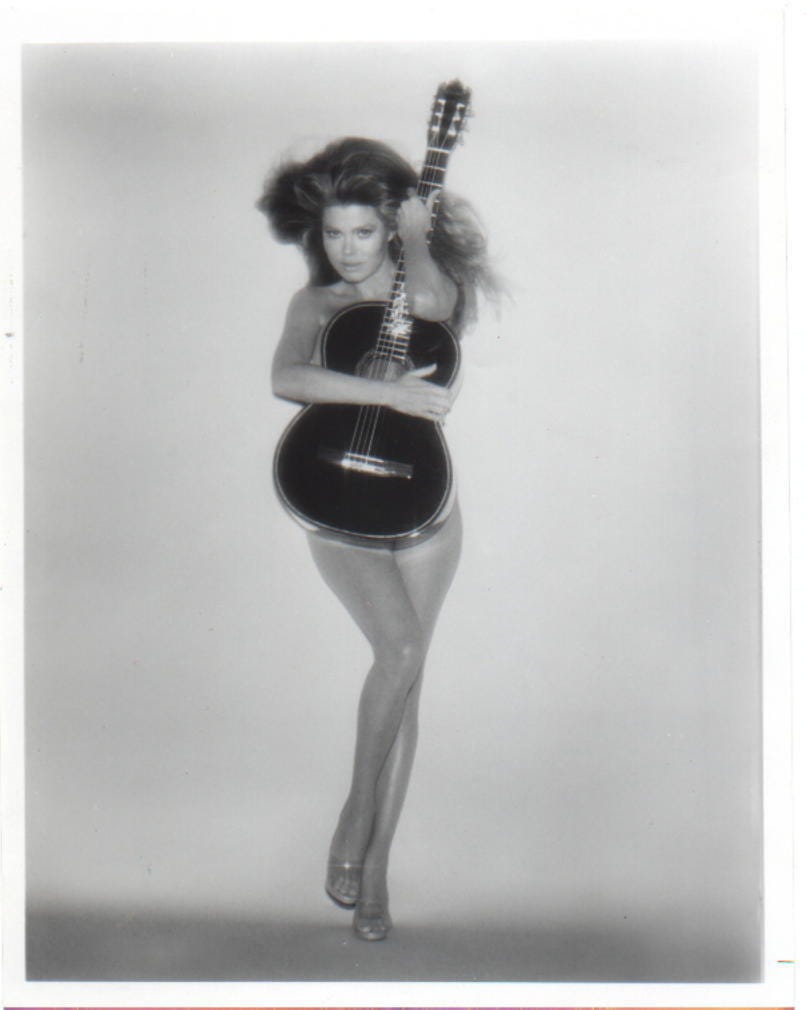

Charo Talks Classical and Flamenco Guitar—Seriously!

A Revealing 1979 Interview With the Spanish Entertainer

Most people who’ve seen Charo on TV or onstage in Las Vegas tend to regard her as a well-rehearsed entertainer who delivers her comedic schtick with large doses of malapropisms and fiery cuchi-cuchi. Behind this façade, though, is a highly accomplished musician who’s spent decades playing flamenco and classical guitar. During the 1970s and ’80s, readers of Guitar Player magazine were certainly aware of her talent, as seen by her many wins in the “Flamenco” category of the annual Guitar Player Readers Polls.

In 1979 Charo released an extraordinary album called Ole! Ole!, which included a version of Rodrigo’s “Concierto de Aranjuez” set to—cue gasps from classical purists—a disco beat. As a staff editor for Guitar Player magazine, I couldn’t resist reaching out to Charo for an interview. On July 27, we connected via telephone. As you’ll see in this exact transcription of our conversation, Charo appreciated being asked about her musicianship.

###

How are you?

Good. How are you?

I better talk as clear as possible because without look to your face it will be difficult for you to know what the hell I am talking about.

Charo, when did you start playing guitar?

When I was very little. My first guitar was given to me by my grandmother when I was around eight or nine year old. Little, cheap guitar that I still have it here in the States. But I didn’t start with good teachers until I was 13 year old.

What style did you learn first?

Flamenco! The Spanish flamenco, which is six strings and you play with the fingers. You never use the pick. It’s the only way I can play. As a matter of fact, you’ll be surprised. I play banjo like I play guitar. I don’t know how to use the pick, so I play banjo with the finger, like if I play flamenco. It’s funny because I was doing a TV with Roy Clark, and I could play as fast as he does. But not with a pick, with the fingers [vocally imitates a trill] like when I play flamenco.

Is it true you played your first concert when you were ten?

No, no. No, no. no. When I was nine and ten and eleven and twelve, I already play guitar, but I was just a lousy young guitar player. But what I did was in the school it was a play. Every Christmas the nuns put together a play that is about the baby Jesus born in the virgin Maria, and the little angel. I was a little country girl going singing and playing my guitar to offer my singing to the baby Jesus. And that night, when we were doing that play in the school—they had like a little theater—the father of one of the girls that was in the play was a writer, like you. A newspaper writer. He just loved me. And he write something very nice about the little town where I was born, Murcia, and said I had potential talent—“little girl that play good guitar and sing very good.” I consider that like the night of my life. The next day I acted already like I already made it! But that was my first appearance playing and singing with a guitar. Nothing professional. But the nuns every year put that play together.

You studied the guitar very seriously, right?

Oh, yes! I do that.

How many teachers have you had?

Many! None of them famous. In Spain we have what they call cace—c, a, c, e—which is a flamenco nightclub where people put a show together for the tourists. All the tourists go, have a drink, and watch singer and dancers doing the real flamenco. I had been practicing and working for free. What I did was when I played the guitar good enough—I was 15 years old, I was living in Madrid—I just go at night. And for free—just they give me the dinner—I sit down and play with them and listen to their way, because nobody know any better than a real Gypsy when they play guitar. Nobody!

So they were your best teachers?

That’s right! I play with them and I listen. I know how they clap, how they do rasgeado [strumming the strings with the finger to produce an arpeggio], everything. So I did that over and over. Even when I was working in America, I’d come back on vacation. My name was getting real big—I didn’t care. I get lost and I sing and I dance and I play the guitar with them over and over. There are places in Madrid. Their general name is cace. There is many different names, and they’re very expensive to go in, because it’s just for tourists. You have to pay with dollars. And the tourists love it because it’s something new, you know. You see the dancer with the Spanish flamenco color, and the singer singing real [sings a flamenco melody]. Any time that I’m on vacation, and every time that I go back to Spain, I just sit down with them and I play and sing. I do it for nothing, but I got everything I need.

Did you eventually study with some well-known guitarists?

Oh, with everybody! The Tárrega teacher—the Tárrega family, at school. I have been with the best of them. Then I have been with [Narciso] Yepes. Yepes is an unknown guitar player in United States, but he is the best guitar player ever born in Spain, to my knowledge. Segovia is excellent.

You studied with Segovia?

I attended to the general teaching that he does. I don’t know if he does it now, but a few years ago, every summer he used to go with the good, good student for free. Study with him, he go and give a general lesson.

What did you study with Yepes?

Narciso Yepes—he’s the best guitarist. He play with emotion.

What did he teach you?

The tremolo. What I play with my guitar, the tremolo. What I do with the fingers—I don’t know what it is in English.

How much time did you spend with Yepes?

I could not afford Yepes! Narciso Yepes is like Segovia. It’s just that they don’t know him in the United States. I studied with Yepes the same way I study with Segovia. I study with everybody else. Those big guitar players, once in a while they go to a certain part of the school or university and they give a general lesson and lecture. And you had to be very much prepared and aware because he’s not going to sit down in front of you and tell you what to do–he just tells you to “ronde” or something like that. Then he give a concert for free and then you listen. I have all his books, all his records.

So you went to master classes.

Oh, yes. I couldn’t afford to have Yepes or Segovia as a private teacher!

Can you read music?

Yes. I learned to read music in the school, in the convent. I cannot read a whole symphony, but I can read note by note.

How seriously do you take the guitar?

Very much. The guitar is like my friend, and it introduced me to the people that love music in a different way than the disco music or my general image on television allow. When I play in person, the guitar is the greatest song that I have to show to the people how much I’m ready for them and how much I respect them. Because the guitar is a very difficult instrument. With the guitar I am available to express my feeling and my emotion, and they love it. It’s a very important part of the act.

What are your favorite pieces to play?

I’m crazy for “Concierto para Aranjuez,” which nobody know in the United States.

Why did you add a disco beat to your recording of that concierto?

Because I try to introduce it to the young kids with the disco dance. It is like when you try to give a kid a vitamin, but it taste of chocolate. Without destroying it at all. If you listen to the album, I don’t destroy one single note. I just put in the disco beat. As a matter of fact, it’s a big hit right now in Spain. They will dance with and become familiar to the melody. In South America, Manila, and Spain, it is selling like mad. In the United States I didn’t think they’d like it with that song, but I think it’s because of promotion. If the promotion doesn’t pick up the song, it’s impossible.

How much do you practice?

Right now I am in the amount of three hours a day. But when I am working, that I just finished yesterday, yesterday I practiced four to five hours. Because the guitar is a very—as you know—unfair instrument. Once you don’t practice at least for a week, you still have it—because it’s all my life—but the finger meets a kind of difficulty. And I notice that it is better to go every day two to three hours—even if I don’t work—than to cool it for a week because then I have to start all over again.

What do you do when you practice?

I lock myself in the smallest room of the house. Or if I have to be around people, I put a piece of cloth between the strings and the guitar so I can practice without making noise.

What do you play when you practice?

Scales. All kind of scales.

How many fingers of your right hand do you use?

In my right hand, when I do picado, I only use the first and the middle. I don’t know how to explain to you this. What is the first?

The index.

The index and the middle. That is when I do picado, or melody. When I do tremolo, I use all of them: I use the thumb, and I use the index, the middle, and the next one.

What do you consider to be the best pieces in your repertoire?

For the people in the United States, I have tried every Villa Lobos, Tárrega, “Concierto para Aranjuez.” The one that they do really applaud because they know—everybody—is a flamenco version of “Malagueña en Granada.” No matter how much they applaud everything—because they love guitar—I must tell you that in the United States you can feel it. They do love and respect everybody that come across and play a good guitar.

What’s the difference between your playing in the U.S. and your playing in Spain or Latin countries?

When I play in Europe, they can take more unknown pieces because they just applaud the technique even if they don’t know what I am playing. When I play in the United States, people are very educated and just because it is a guitar they will listen and they will applaud. But their reaction is much different when I am playing something that they know and is very popular and they can follow me and see the style that I’ll give it. I do play “Recuerdos de la Alhambra,” which is a beautiful old tremolo. And then when I use all the fingers, they love it and they applaud it. But you cannot compare the intensity of the applause when I go into a flamenco spectacular version of “Malagueña en Granada.”

Is that your favorite piece?

No, it’s everybody’s favorite piece! I’ll tell you that any good piece of guitar is my favorite, but if I want to have a big applause, I know I have to do that and then people go wild. And then I keep their attention to continue playing.

What kinds of guitar do you use?

A Ramirez. It’s made out of palo santo—it’s a kind of wood.

Was this made by Ramirez in Madrid?

Yes. I think it was a very old guitar. It used to be used by Segovia, but when I got it I got to change the neck because Segovia has a huge hand. Segovia’s hand is bigger than…I don’t know. My hip! [Laughs]. And I had to make a smaller neck because it is impossible to play the guitar of Segovia because he has the biggest fingers you ever saw in your life.

How many guitars do you have?

Three. Two Ramirez and one Goya. My favorite guitar is the other Ramirez. Nobody knows who it belonged to, and I buy it around six years ago for $3,000 in pesetas. I bought it in Madrid. And the sound of the bass, the lower, of that guitar is the greatest that I have ever heard in my life.

What kind of strings do you use?

Savarez. I change them every two or three days because I play heavy.

Who takes care of your guitar?

Myself! I travel with, I sleep with. When the weather is cold I cover it. I take good care of the guitar. It’s like it would be my baby! I tune the guitar. And now, believe it or not, people in Japan—this sounds very funny for everybody, but it’s working. They created a little tiny machine that is a tuner. You know, to tune the guitar. Which is perfect. Nothing is better than the ear, but it’s as close as you can get. So I tune my guitar and I take care.

What do you look for in a guitar?

I’m looking for a great tone. I love the sound of the guitar! Segovia has been fantastic for the guitar player, because Segovia make the guitar a respectful instrument for classical, for concerts. What I am looking for is to program myself with a good two hours of music, and whenever I have the time between my personal appearances in Las Vegas, go and play around with symphonies in different parts of the United States. I would love to do that! And I would love to go to New York and Philadelphia and everywhere. I have played with orchestras. I have been in Madrid, I have played with different ones. But not with a whole program. Let’s call it “Charo in Concert.” That is part of my future dreams in the nearest future—maybe it could be even be in the 1980s or much later than that.

So you’d like to do full-scale concerts.

Yes! To begin with, I am very happy that you are asking me those questions in this kind of interview. In fact, it’s kind of new for me because most of the newspapers and the audience, they don’t know that side of me. They go for the cuchi-cuchi and the comedy part and the excitement, which is okay, but not many people know how serious musician I am. And I appreciate it very much.

Music is close to your heart.

Oh, it is the most important. Listen, when I get headache or I am in a bad mood or the day just started when I feel real blue and frustrated, I just go to the guitar and play, play, until I get tired and I feel better.

What advice would you give a young woman who wants to have a career as a flamenco or classical guitarist?

I would suggest that she have to have a lot of patience. The secret of a good guitar player is 50-50. 50 talent and 50 perspiration and patience. It’s over and over the same thing again. You play hours a day the same scale. And when you are very tired, cool it for a while and come back. And if they have the chance, go to Spain until they are ready. Stay there for a while, because the only way to play good flamenco is being lost with the flamenco player—the real Gypsy. Forget the famous teacher. I play certain things, certain modulations, that I’ve gotten from old, old Gypsy people. If they get the chance when they are ready, go to Granada and Andalucia, Malaga, and get with them for a while. Listen how they do the real flamenco. That’s my best of my recommendation.

Is there anything you’re working on now, any new pieces that you’re trying to learn?

I am right now in Villa Lobos. I want to make a medley of Villa Lobos. I want to put it in the program for my future dream of the symphony.

Thanks a million for the interview, Charo.

You are beautiful! You really are beautiful and you’ve made me very happy because this is the only interview I’ve had in years that I can talk. That is something new for me.

Oh, thanks, Charo.

Thank you! I hope you like it, and I hope you got what you want.

###

I am happy to report that 45 years after this interview, Charo continues to give concerts. For upcoming dates and other info, check out her Charo Cuchi-Cuchi website.

###

Help Needed! To help me continue producing guitar-intensive interviews, articles, and podcasts, please become a paid subscriber ($5 a month, $40 a year) or hit that donate button. Paid subscribers have complete access to all of the 200+ articles and podcasts posted in Talking Guitar. Thank you for your much-appreciated support!

© 2025 Jas Obrecht. All right reserved.