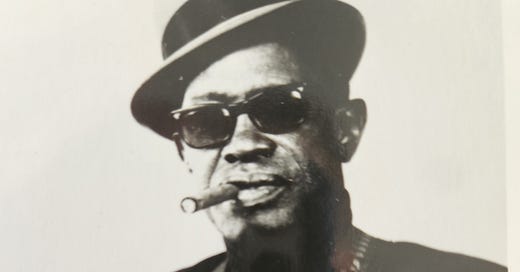

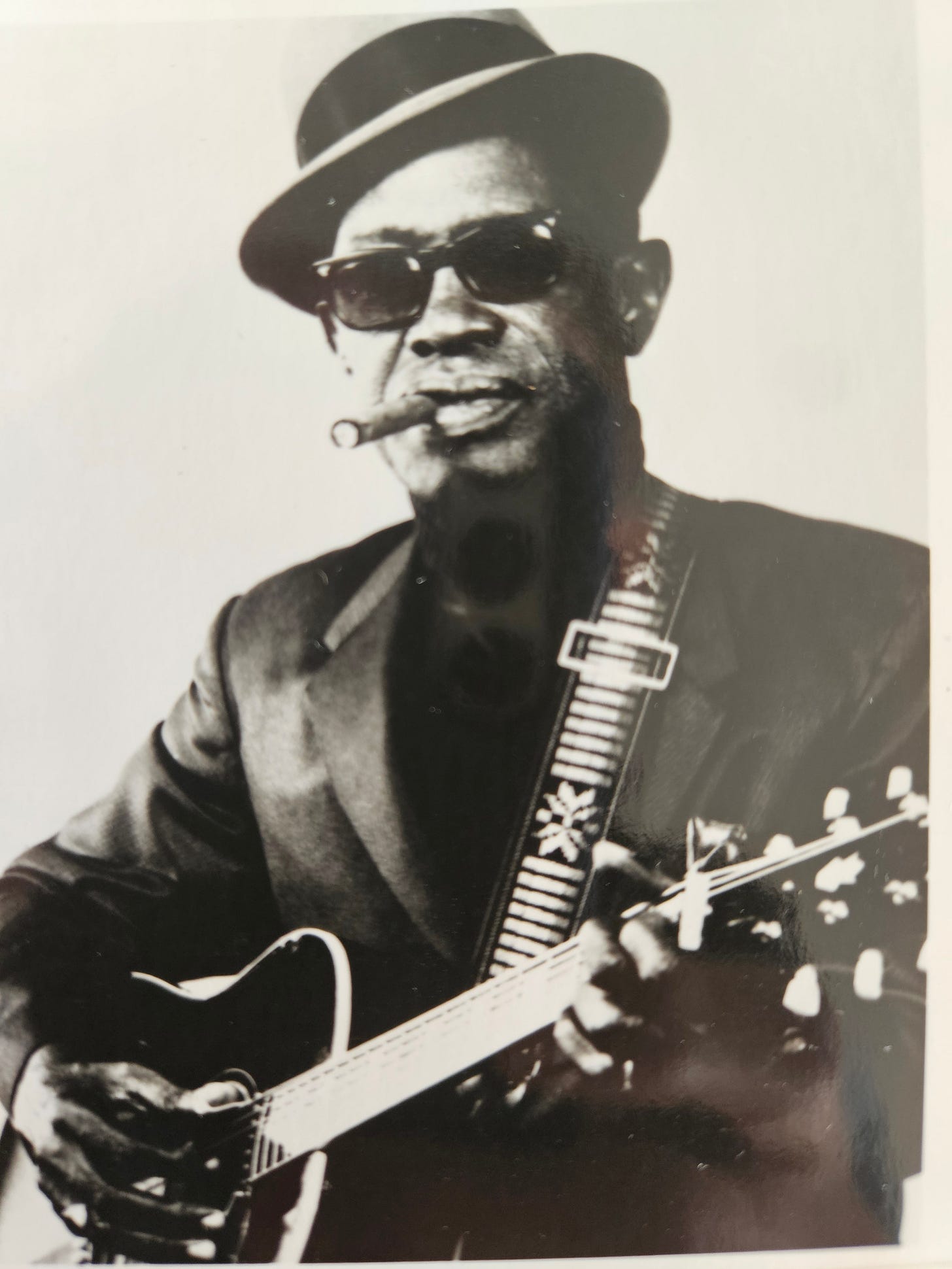

On hundreds of records, Lightnin’ Hopkins demonstrated a rare ability to turn tales of woe into uniquely personal—and often fierce—songs. He could just as easily be lighthearted, charming, rascally, wise, and impetuous. By the time of his death from pneumonia on January 30, 1982, he was regarded as one of the finest poets and performers of Texas-style country blues.

A few weeks after Hopkins’s funeral, I asked B.B. King, Johnny Winter, and Billy Gibbons if they’d be willing to be interviewed for a Lightnin’ tribute I was putting together for the June 1982 Guitar Player. To a man, they all agreed. B.B., of course, was Hopkins’s peer. Lightnin’ had opened several shows for Johnny Winter, who included a cover of Hopkins’s “Back Door Friend” on his breakthrough 1969 album [here’s Johnny’s interview: Johnny Winter: Our 1982 Interview About Lightnin’ Hopkins]. Like Hopkins, ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons lived in Houston, and he had vivid memories of his close encounters with him. Here’s our 1982 interview.

***

Hey, Billy.

Hey, amigo.

I’m doing a tribute to Lightnin’ Hopkins and a read a report that you’d played with him at one time or another.

Yeah. I’ve got a great story. Dusty and Rocky Hill—my bass player and my bass player’s brother Rocky—invited me to come down and see him play one night. They were playing with Lightnin’, and they wanted to know if I wanted to sit in. I said, “Sure, I’d love to!” They said, “But watch yourself.” [Laughs.] I said, “Well, what do you mean?” They said, “He’s tricky. He don’t play by the book.” So I said, “Alright.”

We were playing a traditional blues, and it came up to the second change [the IV chord] where you think it would normally be, and we all went to the second change. Lightnin’ was still in the first change! He stopped and he looked at us. Dusty said, “Well, Lightnin’, we all went to the second change. That’s where it’s supposed to be, isn’t it?” Lightnin’ looked back and he said, “Lightnin’ change when Lightnin’ wanna change.” And we knew—don’t do that no more! [Laughs.] That’s just a funny little story.

Can you describe what distinguished his style?

His turnaround in the key of E. You’ll have to give me a minute to think about it. I don’t know how to really describe it in words right off the bat. [Pause.] He did this thing—it’s a signature lick that he did in every song he played, man. If he was in E, he would come down from the B. He would roll across the top three strings—the E, the B, and the G—and resolve on the V after doing this roll. The pick would hit the little E string, and then it would hit the B string, and then it would hit the G string—da, da, da. He would just kind of pull the pick against those three strings and get kind of a staccato effect. He’d hit the open E string, and his first finger was on the B string third fret and the second finger—the middle finger—was on the G string’s fourth fret. And it was immediate identity for a Lightnin’ Hopkins tune. You knew it was him playing it. The easiest blindfold test in the world would be to hear him do that thing.

Where was he at his best—what kind of gig?

Mostly he would really shine in front of a dancing crowd, in front of a noisy crowd. Later, when the blues became such a studied thing for a lot of white folks, he would concentrate on talking blues. But, man, you put a dancing crowd in front of him, and he would turn that old Stratocaster up. Later on he played a Stratocaster through a variety of amps—just what was available. But it would always get loud when the crowd was right.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Talking Guitar ★ Jas Obrecht's Music Magazine to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.